Pacciolla

Analytical Approaches to Music of South Asia, Volume 1 (2023)

The Musical Journeys of a Goddess

An integrative analysis of drumming, dancing, and ritual in the contemporary Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu of central Kerala[1]

Paolo Pacciolla

Author information: Department of Performing Arts, Christ University (email: paolo.pacciolla@

Received May 17, 2022; Accepted pending revisions January 18, 2023; Revised version received May 3, 2023; Published December 28, 2023.

Abstract: Kaḷameḻuttu is a unique ritual art form of Kerala which revolves around the drawing (eḻuttu) of the anthropomorphic or geometric figure (kaḷam) of a deity made on the floor with coloured powders. Associated with various gods and communities of performers, it includes pūjās,singing, drumming and dancing and reaches its climax when the performer in a state of trance gives oracles to the participants. Over the last century these rituals have been mostly intended and studied as folk arts practiced by communities with different positions in the social order and described in their contemporary forms. On the basis of fieldwork and textual sources which look at kaḷameḻuttu inits historical and religious evolution, this article studies some aspects of the contemporary kaḷameḻuttu in the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition. The first part of the article suggests a reconstruction of the religious cults and ideas which contributed to create the ritual in its present-day form. It argues that kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu is a highly refined ritual evolved in Kerala during the medieval period in the context of Śākta cults for the worship of war deities and that the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus tradition emerged as a consequence of a process of Brahminization of the Śākta ritual. The second part describes and analyses the main sections of the ritual focussing on drumming and dance. The third part analyses the role and ritual meaning of the sword, the drums and rhythmic cycles (tālas), and the oracle dances. It concludes arguing that the contemporary kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu of the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition, notwithstanding the Brahmanical reshaping, still maintains aspects which show that it was a Śākta ritual performed to worship fierce deities connected to war and battlefields.

Keywords: Kerala; Kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu; drumming; oracle dance; Śākta ritual; music analysis

© 2023 by the author. Users may read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of this article without requesting permission. When distributing, (1) the author of the article and the name, volume, issue, and year of the journal must be identified clearly; (2) no portion of the article, including audio, video, or other accompanying media, may be used for commercial purposes; and (3) no portion of the article or any of its accompanying media may be modified, transformed, built upon, sampled, remixed, or separated from the rest of the article.

To view an image (figure, example, or table) at its original size, right-click (or control-click) on it, and select “Open image in new tab.” To download an image or a video, select “Save image as” or “Save link as” instead. (The latter can be helpful when accessing a longer video, which might load slowly.)

Click here to read the PDF version of the article

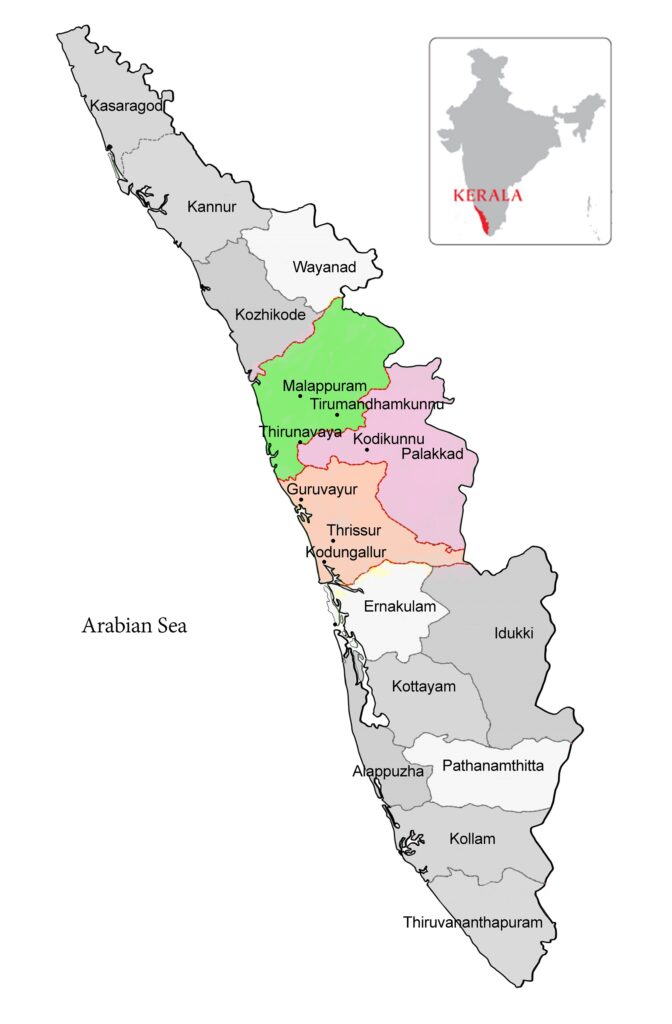

[1] Kaḷameḻuttu is a unique ritual art form of Kerala that revolves around the drawing (eḻuttu) of the anthropomorphic or geometric figure (kaḷam) of a deity made on the floor with colored powders.[2] It includes pūjās, singing, drumming, and dancing, and culminates in the oracle proffered by the main performer in a state of trance. The kaḷam is associated with various gods, and communities of performers who maintain it. Kuṟuppu, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, Tīyyāṭuṇṇi, Tīyyāṭi Nambyārs, Maṇṇāns, Puḷḷuvans, Paṟayas, Tīyans have their own gods and kaḷams and perform in their own temples or in temples of other communities according to established rules.[3] The Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus perform kaḷameḻuttu for the goddess Bhadrakālī, Vēṭṭaykkorumakan, the archer god son of Śiva and Pārvatī, and various minor forms of Śiva. Tīyyāṭi Nambyārs maintain the tradition of Ayyappan tīyyāṭṭu, a form of kaḷameḻuttu performed for the god Ayyappan, son of Śiva and Viṣṇu’s manifestation as the enchantress Mohini. The Puḷḷuvans draw nāgakkaḷams, kaḷams for the serpent gods. Maṇṇāns, Kuṟuppus, and Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus draw kaḷams for Bhadrakālī and accompany their songs with the string instrument nantuṇi, but the right to perform in Brahmanical temples as well as in Nampūtiri Brahmans and Nāyar noble houses belongs exclusively to Kuṟuppus, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus and Tīyyāṭi Nambyārs.[4] Puḷḷuvans and Maṇṇāns perform for Nāyars and low caste groups.

[2] The rituals of some of these communities have been studied by folklorists, anthropologists, and scholars of performing arts (Guillebaud 2008; Neff 1995; Caldwell 1995; Laurent 2004; Tarabout 1986; Choondal 1978 and 1988; Namboodiri 2020; Sathyapal 2011),[4] who, generally, consider them as folk traditions of Dravidian origin.[5] These studies provide valuable information on single traditions. However, they do not analyze the different forms of rituals and kaḷams in a comparative way and, hence, do not point out the distinguishing features of the various worship procedures, the different histories and aims of the cults, and the iconographies of the deities represented in the kaḷams.

[3] Two notable exceptions to this kind of approach are the studies of Jones (1981 and 1982) and Shibi (2018). Jones analyses the ritual and its contexts focusing on the kaḷam as a visual art form and, investigating its relationship with the mural painting tradition of Kerala and neighbor states, suggests that it might have reached its present formal stylistic evolution between the 13th and the 15th centuries (Jones 1982). Shibi proposes a new approach to the different forms of kaḷameḻuttu and similar floor drawings on the basis of iconographic, cultic, and historical analysis and distinguishes three main classes:

- maṇḍalams, patmams, yantrams, and cakrams are symbolic and aniconic figures drawn in temple rituals as well as in residential sites during rituals related to the cult of progeny, fertility, and healing practices. They are drawn by members of almost all the groups of society, including high-status Brahmins and low-status groups such as Maṇṇāns, Tīyyans, Kaṇiyans, and Puḷḷuvans;

- kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu (song) is a ritual including anthropomorphic representations drawn to worship ferocious and war deities such as Bhadrakālī, Vēṭṭaykkorumakan, or Ayyappan in residential houses, shrines (kāvus) and Brahmanical temples by members of the communities known as ambalavāsi. This group includes musicians and temple ritualists such as Teyyampāṭi Nambyārs, Teyyampāṭikuruppus, and Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus;

- kaḷampāṭṭu and mantravādakkaḷam are rituals including anthropomorphic forms drawn to worship both ferocious and pacific deities, such as Cāttan, Kāḷi, Gandharvan, Bhairavan, Guḷikan, Yaksi, Yakṣan, in order to obtain progeny and during healing practices. They are performed in residential sites by members of major non-Brahmin low-caste groups such as Maṇṇāns, Vaṇṇāns, Tīyyans, and Kaṇiyans (Shibi 2018, 72).

[4] This valuable categorization sets the ground for further systematic studies of the different communities and their beliefs, which would help create a more detailed and nuanced picture of the different varieties of kaḷameḻuttu.[7] However, Shibi does not take into consideration two crucial aspects, which relate to the ritual specialists and to the music making. Indeed, while in most of the non-Brahmin low caste groups musicians, dancers, priests, and oracles belong to the same community, in the case of temple connected groups, such as Kuruppus, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, Teyyampāṭi Nambyārs, and Teyyampāṭikuruppus, the situation is more nuanced. This is not the place to discuss the issue in detail, but it may be summarized by saying that, generally, rituals of communities associated with temples need Brahmins to act as the highest ritual specialists and Mārārs or Poṭuvāls to perform as the main experts of ritual music.[8] Another important aspect relates to the oracle. In this case, when kaḷameḻuttu is performed in a temple or a shrine having a permanent oracle (Veḷiccāpaṭu), he will be the performer; when it is performed in private residencies, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus or Teyyampāṭi Nambyārs themselves will perform as oracles.

[5] This article studies the tradition of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu—intended as a class of kaḷameḻuttu according to Shibi’s categories—in the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition.[9] I maintain that the ritual procedure in its contemporary form results from the integration of ritual actions and religious ideologies of various classes of ritualists—namely Brahmins, Mārārs, Kuṟuppus, and Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus—and that in this ritual performance music and dance are ritual actions embedded with meaning.[10] In the first part of the article, I will suggest a reconstruction of the religious cults and ideas which contributed to the creation of the ritual in its present-day form. On the basis of fieldwork and textual sources,[11] I will argue that kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu is a highly refined ritual that evolved in Kerala during the medieval period in the context of Śākta cults for the worship of war deities, and that the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition emerged in the Thirumandankunnu temple as a consequence of a process of Brahminization of the Śākta ritual.[12] In the second part of the article, I will describe and analyze the main sections of the ritual, focusing on drumming and dance.[13] In the third part, I will analyze the role and ritual meaning of the sword, the drums and rhythmic cycles (tālas), and the oracle dances, and I will argue that the contemporary kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu of the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition, notwithstanding the Brahmanical reshaping, still maintains aspects which show that it was a Śākta ritual performed to worship fierce deities connected to war and battlefields.

Figure 1. Map of Kerala.

KAḶAMEḺUTTU PĀṬṬU AND THE KALLAṮṮAKUṞUPPUS

The king should at night draw the figure of Bali having two arms, in a circle made on the ground with five colored powders; […] the king should offer worship in the midst of his palace together with his brothers and ministers with several kinds of lotuses and offer sandalwood paste, incense, and naivedya of food, including wine and meat […]. Having thus worshipped, he should keep awake at night by arranging for dramatic spectacles presented by actors, based on the stories about Kṣatriyas (Jones 1982, 70).

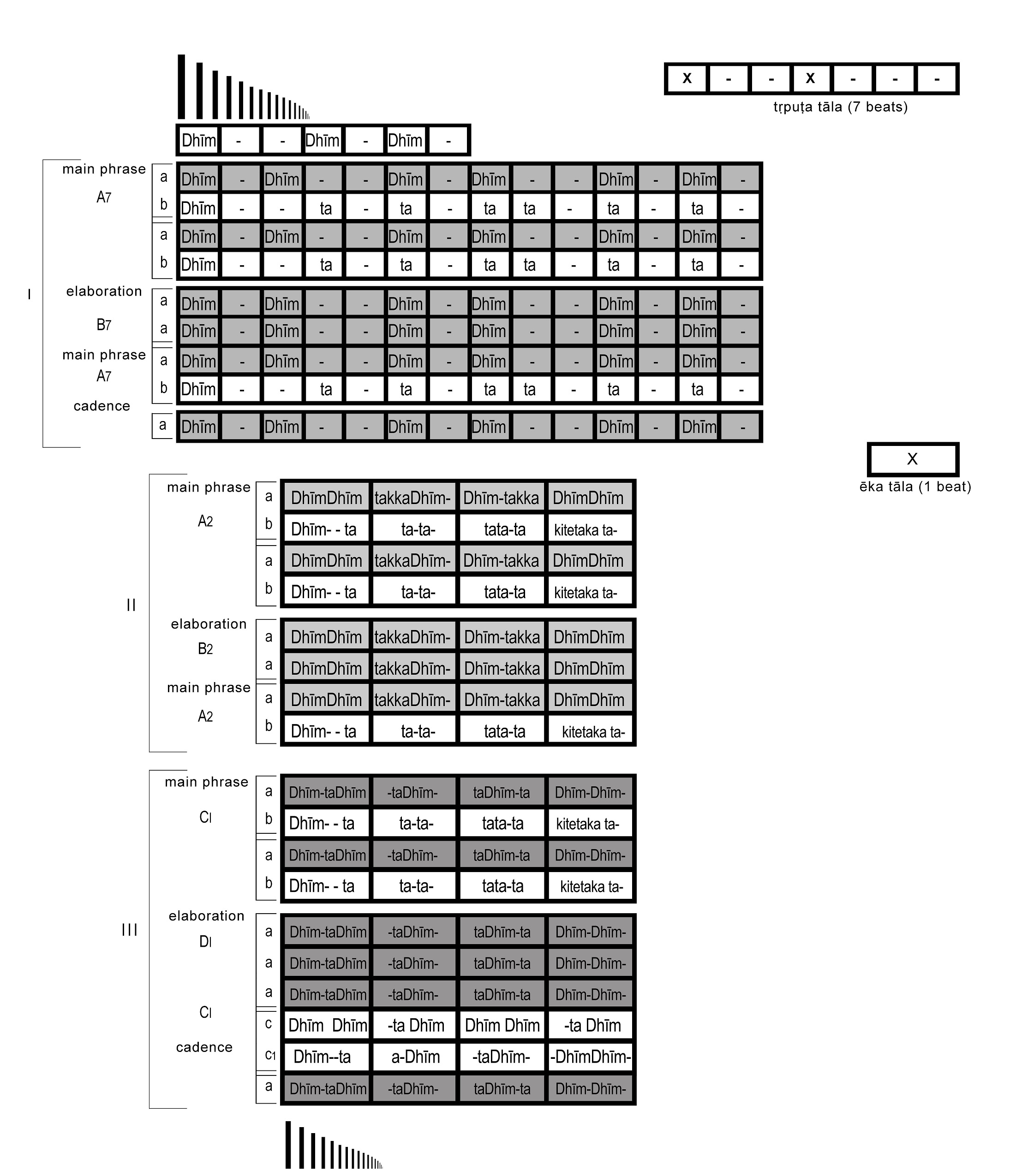

[6] According to Jones, this quotation from the Bhavishyottara Purāṇa (6th to 8th century) is the very earliest reference to an elaborate ritual similar to the contemporary kaḷameḻuttu pattu (Jones 1982, 70). However, the first evidences of kaḷameḻuttu in Kerala are to be found in the granthavaris, which were accounts dealing with various political and ritual affairs maintained by the major ruling families and temples of Kerala and covering from the 15th to the 19th century. The Kōḷikkōṭan granthavari (15th to 18th century) of the Zamorin royal family, the Vaññēri granthavari (16th to the 19th century) of an important Nampūtiri Brahmin family of Trikkandiyur village, and Kūṭāḷi granthavari (16th to the 19th century) of an aristocratic Nāyar family of North Malabar, are the most important among them (Shibi 2018, 39–41; Haridas 2003; Nampoothiri 1999). Along with other literary sources which provide a great deal of information on the cults and the deities worshipped through kaḷameḻuttu, they show that the main sponsors of kaḷameḻuttu were the rulers of the kingdoms which emerged around the 13th century C.E. after the fall of the Cēra empire and ruled for centuries thereafter (Gurukkal and Varier 2018; Nampoothiri 1999). They were warriors, and worshipped Bhadrakālī and the seven mother goddesses (Sapta Mātṛkas) in their family shrines and royal temples to gain success in battle. In a similar way, gods such as Vēṭṭaykkorumakan and Ayyappan were adopted as fierce warrior-deities by royal families and worshipped with kaḷameḻuttu (Shibi 2018, 39–41; Haridas 2003, 237). Along with their rulers, Nāyar chieftains worshipped these gods for success in battle. Bhadrakālī and the Sapta Mātṛkas had and still have a special place in the martial training centers (kālari), where an altar is built in the southwestern corner of the hall, and the first salutation at the beginning of the training is offered to them (Balakrishnan 2003). Even Brahmanical families, typically belonging to non-Vedic traditions, patronized kaḷameḻuttu (Shibi 2018; Nampoothiri 1999). It is in medieval records that kaḷameḻuttu and pāṭṭu merge, and we find mentions of Vēṭṭaykkorumakan pāṭṭu andBhadrakālī pāṭṭu (Shibi 2018, 39–41; Haridas 2018). Interestingly, the texts of the songs, which are a mixture of early Malayalam and medieval Tamil, suggest that they were composed around the 14th–15th centuries and even the style of drawing of the contemporary images may be approximately dated to the same period (Jones 1981, 280; Nampoothiri 1999).

[7] While the granthavaris provide information until the 19th century, the British ethnographic surveys help us understand the practice of kaḷameḻuttu in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The most significant among them are those by Iyer (1912) and Thurston and Rangachari (1909), who provide descriptions of the ritual as performed by different caste groups in their temples or private residences.

[8] After the Indian Independence in 1947 and the creation of the state of Kerala in 1956, the entire society underwent dramatic changes that significantly affected ritual arts and associated forms. One of the most significant changes was the land reform (1957), which strongly affected temple activities and organization as well as temple communities (Gurukkal and Varier 2018). As a consequence of the reform, the land owned by temples was expropriated and distributed among the lower groups of the society; all the temple functionaries, whose income was granted by temples in terms of land and goods, were forced to look for different jobs. The kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu performers I had conversations with emphasized the difficulties faced by their group in that period, and highlighted that it caused a weakening of the tradition.[14]

[9] However, over the last few decades, thanks to the interest of scholars of arts, literature, and folklore, and the effort of various representatives of the different traditions, kaḷameḻuttu has been considered under a new light, and it has contributed to a fruitful revival of the ritual art form. Furthermore, the new social and cultural organization has contributed to the creation of new venues for the performance, a new public for the ritual art, and even new ways to look at it. In fact, kaḷameḻuttu has recently started being appreciated and reappraised for its artistic value, and has been patronized by private organizations and government institutions. One of the most interesting initiatives was undertaken in 2010 by the Kerala Lalit Kala Academy, which organized forty days of performances of kaḷameḻuttu presented in most of its different traditions (Sathyapal 2011).

[10] Shibi (2018, 22–23) points out that while the practice of a ritual involving the drawing of a deity on the floor may be traced back to the 13th or 14th century, the colonial surveys show that the term kaḷameḻuttu, which had primarily been used for the tradition of floor drawing of the ambalavāsi groups, became prevalent to define any form of floor drawing from the 20th century onwards. Interestingly, it is also in the colonial surveys that we find the first mention of Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu as a group of performers of kaḷameḻuttu, and, in the same period, Gundert’s “Malayalam Dictionary” gives ‘Kaḷa Kuṟuppu’ as an alternative name of the class of priests and painters called Teyyampāṭis (Gundert, 1872). Indeed, granthavaris refer to Teyyampāṭis and Komarams (oracles) as the communities of professionals associated with kaḷameḻuttu (Shibi 2018, 276).

[11] Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus are a sub-group of the Kuṟuppu, an important community of ritual performers described by the British ethnographers as a class of priests who draw figures (kaḷam) of the goddess Bhagavati, sing, and play the instrument called nanturni in her temples (Gundert 1872, 273; Iyer 1912, 145; Thurston and Rangachari 1909, 3, 92). The term Kuṟuppu was also an honorific bestowed on distinguished warriors (Thurston and Rangachari 1909, 4, 181; Caldwell 1995, 87). Jones writes that the title Kuṟuppu, which traditionally refers to a master of arms and physical culture, may be derived from the fact that they teach the newly consecrated oracle the long ritual dance which he performs as part of the Bhagavati pāṭṭu ritual (Jones 1982, 288).

[12] The Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus are specialized in the performance of the songs and the drawing of Bhadrakālī, Vēṭṭaykkorumakan, Ayyappan, various minor forms of Śiva, and snake gods (Nāgas). They are mostly settled in central Kerala and are ritually linked with the temple of Tirumandamkunnu at Angadipuram in the district of Mallappuram. When I asked Kalamandalamam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu, one of the most eminent representatives of the community in Thrissur district, what the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus know of their own story, he said that theirs is a Dravidian tradition. In origin, their rituals and devotion were primarily directed to snakes and Śaiva gods whom they worshipped in particular spots in the forest called kāvus. Later on, their tradition was strongly impacted by the arrival of the Nampūtiri Brahmins, who were wealthy and powerful landowners. They subjugated the Dravidians as their helpers, created the caste system, and relegated them to a low-status position. Then, he narrated two myths about the origin of his community. According to the first myth, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus were attendants (bhūta gaṇas) of Śiva on Mount Kailāśā. Once, one of them was drawing the kaḷam of Śiva when the god himself came along with Pārvatī. Śiva tried to look at the kaḷam, but the one who was making it covered the drawing, saying that it was not complete. Enraged by this behaviour, Śiva cast a spell on him and his group saying that they would go to the earth and earn their livelihood by drawing. The man, soon saddened and pervaded by sorrow, asked Śiva to relieve him and his group from the spell. The god calmed down and said that they would go to the earth to draw this form, and when they did it perfectly, they would come back to Mount Kailāśā. On the earth, they became known as Kailāśāttil Kuṟippu, the ones who draw on Kailāśā, and these words, over time, became Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu, which is the contemporary name of the group.

[13] According to the second myth, the goddess Thirumandamkunnu Bhagavati appeared to two Nampūtiris of different families who were performing a pūjā. A servant of theirs who was there secretly took a look and then drew the goddess on a stone, but while doing it, he cut the stone. The name of the community derives from this event since kallu means stone and aṯṯ cut, so they became the ones who draw (kuṟippu) on the broken stone.

[14] While the first myth highlights the association of the group with Śiva and Śāiva deities, the second narrates their link with Thirumandamkunnu Bhagavati and her temple. Interestingly, as narrated in a story reported by Manikandan Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu, the same temple is also known as the place of origin of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu (Haridasan 2019, 14:11–17:48).[15] According to this story, a saint who used to conduct worship in the Thirumandamkunnu temple felt it was time to leave his life on the earth, and taught to two Brahmins the rituals to worship all the gods. However, as soon as they started worshipping, the Brahmins realized they could not complete their duty because they were not able to imagine the form of Bhadrakālī while chanting the prayers. They tried for days but could not manage to imagine it. They had a Nāyar helper with them, and he had also heard the prayers from the saint when he taught them to the priests. Noticing the problematic situation of the priests, he wanted to help them, but was afraid they might feel offended. Thus, he thought to draw on a rock the image of Bhadrakālī he had in his mind. When the priests saw the picture, they were able to complete their worship and became happy. They asked who drew the picture and the helper said he understood their difficulty and decided to help them. They relieved him from helper duties, and since he drew the image on a stone, his family was assigned the name Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu and given the privileges to draw and worship from then onwards. Since then, non-Brahmin priests have performed worship to Bhadrakālī in Thirumandhamkunnu temple (Haridasan 2019). Indeed, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus are not Brahmins and their main community deities are Kuṯṯippurattu Bhagavati, Thirumandamkunnu Bhagavati and Kodungallur Bhagavati, whom they worship in the form of a sword (vāl) and a mirror (vāl kaṇṇāṭi) on a stool (pīṭham).[16]

[15] The Thirumandamkunnu and the Kurumba Bhagavati temple of Kodungallur are the most important Bhadrakālī temples of central Kerala and belong to the group of Śākta temples in the state. These are royal temples (kāvus), where Bhadrakālī is the main deity and sacrifices were once conducted to receive her power and protection on the battlefield (Haridas 2003; Sarma 2015; Ajithan 2015; Freeman 2016). She is the great warrior who killed Dārika, an extremely powerful demon who was challenging the gods. The priests in most of these temples are not Brahmins but belong to the Aṭikal, Mūssatu, and Piṭārar communities and conduct pūjās offering blood and meat (Sarma 2015; Freeman 2016). However, over time, both the Thirumandamkunnu and the Kodungallur temples become controlled by orthodox Brahmins and no longer follow the old Śākta method of worship (Gentes 1992). An interesting story narrated to me by Kalamandalam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tells how, according to a Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu belief, the Brahmins took over the control of the ritual of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu from the Kuṟuppus who used to perform it.[17]

Figure 2: Popular reproductions of the icons of a. Bhadrakālī of the Thirumandhankunnu temple and b. Bhadrakālī of Kodungallur. These and similar pictures may be bought by devotees in the many stalls and shops selling ritual items outside the temples.

[16] According to the story, Kuṟuppus were the ones who had the right to perform all the pūjās for the kaḷam in Thirumandamkunnu temple. One day, one of them drew the kaḷam and went to a nearby river to wash his face and feet before performing the pūjā. Meanwhile, a Brahmin and a musician (Mārār) started doing the pūjā. The Kuṟuppu listening to the sound of the drum understood what was happening and ran back to the kaḷam, but when he arrived there, the pūjā had already been completed. He was disturbed, but could not say anything because Nampūtiris were the lords of the temple. When the Brahmin told him to sing since they had already performed the kaḷam pūjā, he was so confused that he could not remember either the tune or the texts of the songs. He prayed to Thirumandankunnu Bhagavati, asking what to do in such a situation and the goddess granted him the vision that the Brahmin had performed the pūjā for Bhadrakālī, but the pūjā for the Sapta Mātṛkas and the Bhūtas had yet to be done. Thus, he said to the Brahmin that after the song he had to perform a pūjā to make the Sapta Mātṛkas and the Bhūtas happy, and he did it with rice, flowers, areca nut flowers, and with fire offerings (tiriyuḻiccal).[18]

[17] What all these elements and stories suggest is that the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu community emerged in the 19th century when the Nampūtiri Brahmins took control over the Thirumandamkunnu temple and modified its Śākta ritual procedure according to their own system. The Kuṟuppus who used to perform there had to adjust to the new situation and adopt a new name.[19] In fact, the language of their songs suggests that the roots of this community are much older, and the songs themselves provide further evidence of their long heritage and layered history. Although the Thirumandamkunnu Bhagavati and the Kodungallur Bhagavati are the community deities of the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, as clearly stated in the text of the song (pāṭṭu), their origin deity or paradevatā is Kuṯṯippurattu Bhagavati, described as the goddess who reigns at Tiruvāḻur in Tamil Nadu. Furthermore, the kaḷam of Kuṯṯippurattu Bhagavati is different from the kaḷam of Bhadrakālī since the goddess does not hold in her hands the head of Dārika, but an anklet, and is depicted along with a man, known as Nampyaṯṯu Gopalan, who also holds in his hand an anklet. What is interesting to note is, that the goddess and Nampyaṯṯu Gopalan are reminiscent of Kaṇṇaki and her husband Kōvalaṉ of the story in the Cilappatikāram (The ankle bracelet). Indeed, the South Indian literary work narrates the events generated by the decision of the couple to sell one of Kannaki’s anklets to a goldsmith, who was also a thief. This association supports the Tamil origin of the goddess claimed in the song and suggests that the members of the original community, sometime in the past, adapted themselves to perform in Śākta temples. Thus, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu appears to be the last name attributed to a community of ritual performers who moved from Tiruvāḻur in Tamil Nadu to Kerala, adjusting to various religious contexts and groups in different historical periods.

KAḶAMEḺUTTU PĀṬṬU

[18] The period that lasts for forty-one days starting from mid-November (Vṛśchikam) and is known as maṇḍalam is the most important and auspicious time in Bhadrakālī and Ayyappan shrines of Kerala. It is also the main period for the drawing of kaḷams. Kaḷameḻuttu is performed daily in every Bhadrakālī temple—where the goddess is represented by a wooden icon, a mirror, and a sword (vāl) —in its short and simple form which includes: 1) the drawing of a kaḷam of the goddess by a Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu who also sings and plays small cymbals (kuḷittālam); 2) the playing of specific drum compositions by Mārārs or Poṭuvāls musicians; 3) the performance of the worship of the kaḷam (kaḷam pūjā) by a Brahmin; 4) the performance of the worship by waving lighted wicks (tiriyuḻiccal) by the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu; and 5) the dance of the oracle around the kaḷam (kaḷapradakṣiṇa). The figure of the oracle, called Veḷiccāpaṭu, (“the illuminator”), is extremely important in Bhadrakālī, Ayyappan, and Vēṭṭaykkorumakan shrines (kāvus). He—rarely she—is considered an embodiment of the deity of the temple; the deity speaks to his or her devotees through the oracle.[20] The oracle is a major figure in the religious landscape of Kerala, and many communities have a ritualist capable of communicating with a deity in their cults. During special rituals and by means of drumming, dancing, drawing of kaḷams or face painting, and dressing in special costumes, he becomes the receptacle of a deity who can communicate with his/her devotees and give them advice. Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, Teyyampāṭi Nampyārs, and Teyyampāṭikuruppus are performers and oracles, and in kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu they act as such.

[19] The extended form of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu is, at present, performed in Bhadrakālī temples, in important Śaiva temples, such as the Mahādeva temple of Thrittala, in Ayyappan and Vēṭṭaykkorumakan temples, and in private Nampūtiri or Nāyar houses. Three groups of performers are involved in the performance of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu: Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, Mārārs or Poṭuvāls, and Brahmins. The Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus draw the kaḷam, sing and play the nantuṇi, a long-necked lute with high frets, a waisted resonator with little depth, and two metal strings plucked with a plectrum made of horn, and the small cymbals kuḷittālam, perform as oracle dancers, and proffer the oracle.[21] The Mārārs or the Poṭuvāls, the communities of musicians who maintain the exclusive right to play in Brahmanical temples, support and enliven the entire performance with the sound of the cylindrical drum ceṇṭa, both the low-pitched vīkan ceṇṭa and high-pitched uruṭṭu ceṇṭa,[22] the hourglass drum iṭakka, the big cymbals ilattālam, the reed kuḻal, and the horn kompū.[23] The Brahmins do the pūjās.

[20] I will now describe and analyze the full sequence of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu as I have attended it many times performed by Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu in the districts of Thrissur and Palakkad from November 2020 to April 2022. The following description and analysis are based on fieldwork and take into account texts such as Mundekkad (2002), Sarma (2018), Zarrilli (1993), Shibi (2018), archive videos recordings of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, and the documentary ‘Art of dust’ by Haridasan (2019). Although I mostly refer to the kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu for Bhadrakālī, the same pattern is applied to other gods, such as Ayyappan, Vēṭṭaykkorumakan and minor forms of Śiva such as Anthimahākālan and Asuramahākālan (Figure 13) who are included in the pantheon of the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu community.

Preliminary Rituals

[21] A performance of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu starts around nine o’clock in the morning with the clearing of the space where the ritual will be performed. If a temple has a place already set to perform it, kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu may be held there; otherwise, a specific space has to be set for it. In the latter case, four wooden pillars are fixed on the ground to create a rectangular area and are connected at the top by thin planks of wood. Ropes tied in the north-south direction create the ceiling of the structure, which is called maṇḍapam. Then, a white cloth is spread over the ropes, and the pillars are wrapped with white or black cloth. A cloth draped in the shape of a fan (muṭiykkuka), the mirror, and the sword are placed on a stool. The stool is placed at the center of the maṇḍapam, and nearby it, various kinds of offerings are placed (Figure 3). Then, the priest lights a lamp, and the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu receives from the sponsor of the ritual a piece of red silk cloth (kūṟa).[24] The conch is blown three times, and the performer, placed on the eastern side of the maṇḍapam, invokes the deity from the universe into the cloth and then, facing east, unrolls it over the ropes of the ceiling of the maṇḍapam.

Figure 3: The sword and the stool in the maṇḍapam with the offerings and the red silk cloth kūṟa, wrapped in the shape of a circle, placed on a banana leaf on the floor. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Uccappāṭṭu

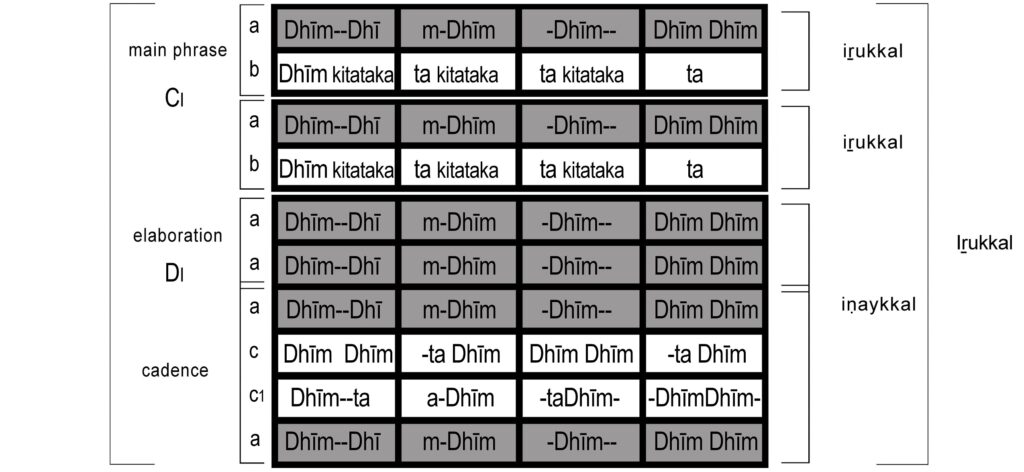

[22] The next stage is called uccappāṭṭu, noon song. A Brahmin performs a pūjā to the sword by means of mantras, gestures (mudrās), and various offerings representing the five elements (pañcabhūtas), which, according to Tantra, constitute life in the universe.[25] While the priest empowers the sword with a pūjā, the drummers play a composition for vīkan ceṇṭas and ilaṭṭālam called sandhyā vela (evening festival). It is a significant piece in the repertoire of the Mārārs and the Poṭuvāls, and it is performed to invoke the gods.[26] It is played on the ceṇṭa held in horizontal position (Figure 4) and is based on specific strokes of the drum. These are ta, an open sound produced by striking the center of the skin of the vīkan ceṇṭa with the stick and soon moving it away, and ta, which is a closed stroke. This means that the stick strikes the center of the skin and remains on it, preventing further vibrations. The stick in the other hand, softly strikes the skin of the uruṭṭu ceṇṭa filling the gaps in the strokes of the vīkan ceṇṭa with the closed stroke called ka.

Figure 4: Thrittala Sreeni Poṭuvāl, in the center, and his ensemble playing the sandhyā vela. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

[23] Sandhyā vela (Example 1, Audio 1) shows very interesting numerical patterns based on numbers two, seven, and six. The number two is particularly significant at the level of the structure. The composition includes two sections:[27] the first one is based on the seven-beat tṛpuṭa tāla and the second on the single-beat ēka tāla.[28] The latter section is further composed of two parts. The main phrases (A7, A2, CI) of each piece are composed of two parts, phrase a and b, which are based on different strokes. Phrase a emphasizes the open sound of the stroke Dhīm and phrase b the closed strokes ta or ka. Furthermore, the main phrases are repeated twice, followed by the elaboration, which consists of the repetition of their a-phrase. Seven appears as the most important number at the level of the main phrases since each one of them includes seven Dhīms. Six Dhīms compose the first part (A7a, A2a, CIa), while the seventh one opens the second part (A7b, A2b, CIb).

[24] It is also interesting to observe how the duration of the Dhīms gradually reduces. Indeed, the Dhīms of the phrase A7 occupy one beat while the Dhīms in the second (A2) and the third phrases (CI) occupy half a beat and a quarter of a beat, respectively. Furthermore, we may see that the number of Dhīms in a-phrases decreases progressively. Thus, while phrase A7a is composed of Dhīms occupying two and three beats, respectively, phrase A2a includes a sequence of two Dhīms followed by two tas, and phrase CIa a sequence of one Dhīm and one ta. All these expedients create the impression of acceleration and the effect that the composition is moving toward its final stroke. We will see that this procedure, which as I have argued in other articles (Pacciolla 2021a and 2021b) is adopted by Mārārs and Nāmbyars temple musicians to invoke the gods in the ritual space, is applied extensively to all the drum compositions performed in the ritual.

Example 1: Sandhyā vela as played in the Thrittala tradition.

The vertical lines of diminishing length indicate the koṭṭi aṟiyikkal (drum beating communication), a sequence of strokes having progressively reduced duration. Each box frames one beat. Syllables indicate the specific strokes played on the drum (see § 24). Dashes indicate rests. White boxes and grey shaded boxes help distinguish and visualize the different phrases (a, grey and b/c, white) constituting each composition sub-section. See § 39 for details on the labels given to phrases.

[25] Soon after the first presentation of sandhyā vēla two Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, sitting on the southern side of the maṇḍapam and facing north, start singing. The main singer accompanies himself with the nantuṇi in order to provide the drone. His assistant sings and plays the small cymbals kuḷitālam. The main singer sings two lines, and his assistant or assistants the following two, and so on.

[26] The first song, called stuti (eulogy), is a praise to various gods. It starts with Gaṇapati, and then moves to Sarasvatī, Kṛṣṇa, and Śiva. A drummer plays the sandhyā vela again on the low-pitched vīkan ceṇṭa, and thereafter the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu sings the eulogy of Bhadrakālī, called niṟaṃ (color). These songs are transmitted by example and imitation. Traditionally, they are not based on rāgas. However, over the last century, the popularity and spread of Carnatic music in Kerala society impacted even the singing technique of the songs (pāṭṭu) in kaḷameḻuttu, and the use of rāgas in singing is now admitted. The songs are based on the seven-beat tṛpuṭa tāla.

[27] Niṟaṃ is the main section of the song and the one that provides a description of the deity to whom the many parts of the song are devoted. Each deity has his/her own niṟaṃ. Bhadrakālī’s niṟaṃ (Audio 2) describes the goddess as

The one who is the sister of Viṣṇu, the god whose body has the color of a dark cloud

She who widely opens the fire eye

She who destroys the army of the big demons and calls them numerous to battle

She who severed the head of the great demon who was ruling the earth and then went to Kailāśā.[29]

[28] Niṟaṃ is followed by vaḻinaṭa (designated path), which is the invocation of the deity from Mount Kailāsa into the maṇḍapam. While the texts of stuti and niṟaṃ are based on meters and may be considered as proper songs, vaḻinaṭa is written in the form of prose and may be better defined as a kind of intoned recitation (Audio 3).[30] With the first lines, the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu invokes the goddess and tells her the path she has to take from Mount Kailāśā to the maṇḍapam, where he has prepared a series of offerings to welcome her. She will enter the world of human beings from the mountains of the sunrise (Udayanā Parvatam) and the sunset (Astamana Parvatam) and then will move from Tamil Nadu to Kerala, going through a number of temples and even Brahmin private houses. The vaḻinaṭa ends by intensely summoning the goddess in the singing maṇḍapam:

I summon you to come here from your origin place in the pāṭṭu maṇḍapam where this kaḷam with all decorations has been made. Lamps, flags of cloth, a mirror, the stool, banana leaves with offerings, flavors, songs, water, women’s procession, water, sandal paste, flowers, smoke, light, food offering, drumming, Vedas, songs, dance, rhythm, beautiful words, and the salutation from the heart. We are doing these fourteen pūjās for you, we are making all these decorations for you, and we are bowing in front of you. Now, I summon you. Oh, beloved Mother Thirumandamkunnu Amma, great goddess, please come here! Origin Mother.[31]

The singing of vaḻinaṭa is followed by a new performance of sandhyā vela, which brings uccappāṭṭu to an end.

The Drawing of the Kaḷam

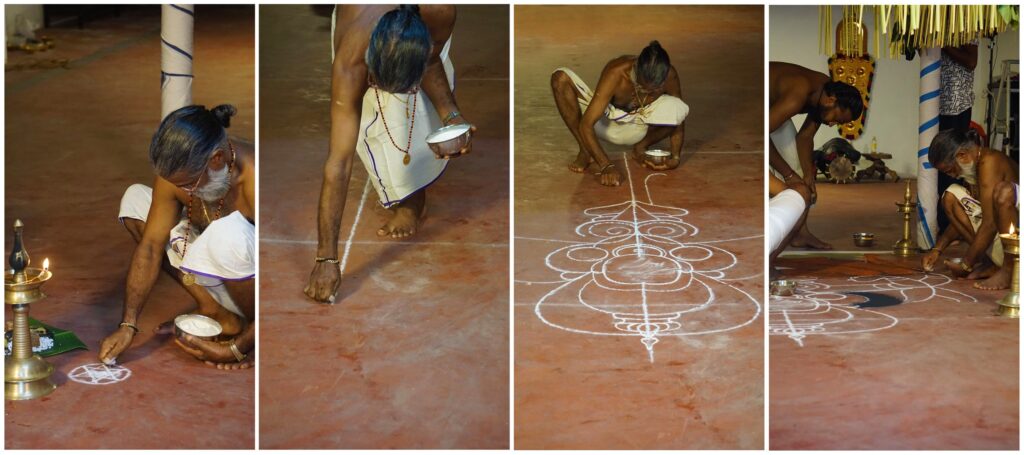

[29] Once these rituals have been performed, the kaḷameḻuttu of Bhadrakālī may begin. It is started by drawing on the south-eastern side of the space a hexagonal diagram for Gaṇapati. Gaṇapati is invoked from the flame of the lamp into the rice powder, which will be used to draw (Figure 5).

Figure 5: First stages of the drawing of a kaḷam. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

[30] Once the image is drawn by using white rice powder spread with the fingers, the colors are added. Five basic colors are used in the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition, and they are identified with the five elements (pañcabhūtas): yellow stands for earth, white for water, red for fire, green for air, and black for ether. In fact, Kalamandalam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu pointed out that the creation of the kaḷam in the consecrated empty space of the maṇḍapam corresponds to a cosmology, the creation of a cosmos with the shape of the body of a deity.[32]

[31] Bhadrakālī is generally portrayed in a sitting position and has two big protruding fangs, three eyes, and eight hands holding a sword, the severed head of Dārika, a spear or a trident, a cup filled with blood, a shield, a bell, a snake and an anklet. The eyes are shaped three-dimensional by creating small mounds of rice powder and giving them a particular inclination. The eyes, particularly the pupils, are the last to be drawn. After that, the kaḷam is considered to be enlivened by the goddess and equated to an idol inside the sancta sanctorum of a Brahmanical temple (Figure 6) (Haridasan 2019, 46:37). The drawing of Vēṭṭaykkorumakan and Ayyappan in their different iconographic models follows the same procedure.[33]

Figure 6: Final touches to the kaḷam: drawing the pupil of the third eye of Bhadrakālī. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

[32] The drawing of the kaḷam lasts three to four hours. When the image is complete the stage is decorated. On the top of the drawing, just above the head of the deity, is placed the stool with the sacred objects. The string instrument nantuṇi is placed on the south side corresponding to the left of the image. On the north side of the maṇḍapam are placed some paddy and guruti, a mix of turmeric powder and lime, which symbolizes blood (Figure 7). Once everything is properly set, a drum ensemble composed by vīkan ceṇṭas plays the sandhyā vēla.

Figure 7. Thekaḷam of Bhadrakālī in the decorated maṇḍapam. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Mullakkal Pāṭṭu

[33] The playing of the sandhyā vēla is followed by a ritual called mullakkal pāṭṭu. Generally, it is performed under a banyan tree outside the temple premises. When it is held in private residences, it is performed in an area slightly distant from the kaḷam. In this ritual, a Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu, wearing a pleated white cloth around the waist and, upon it, a piece of red silk (virāḷi paṭṭa) and a brass belt with bells (aramani), assumes the role of the oracle. The Brahmin performs a short pūjā to the sword placed on the stool, and another Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu sings stuti and vaḻinaṭa again. The oracle receives from the Brahmin a garland of flowers, water, and a sword and is offered songs in sōpāna saṅgīta style (Figure 8). This particular repertoire takes its name for being performed for the gods of the Brahmanical temples of Kerala, near the steps (sōpāna) of the sancta sanctorum. The songs in sōpāna saṅgīta style are typically sung by a Mārār or a Poṭuvāl accompanying himself on the hourglass tension drum iṭakka, and with the support of another musician playing the circular idiophone cēñgilam. Then, holding the sword in his hands and followed by assistants and devotees, the oracle moves in procession towards the kaḷam with the sonic support of an ensemble (ceṇṭa melam) playing a composition (pāṇṭi melam) based on the fourteen-beat atanṭa tāla.

Figure 8. A Mārār, accompanying himself with the hourglass drum iṭakka and supported by another Mārār playing the ilaṭṭālam cymbals, sings for the sword and the oracle, who wears the red silk cloth virāḷi paṭṭa. The man dressed in black holds a lamp with a flame (not visible in the photo), representing the goddess. The man with the red shirt and a third Mārār attend the ritual. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Īṭuṃ Kūṟuṃ

[34] The procession stops in an area in front of the temple or in a space not far from the kaḷam when it is performed in a private house, and there, the oracle, holding the sword in his right hand, dances a dance called īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ. This and the following dance, called kaḷapradakṣiṇa, are regarded by the performers as having the highest ritual importance. The leading role in the īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is held by the drummer who decides the sequence of compositions to play, and the oracle has to follow him.

[35] The music ensemble playing īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is generally composed by two or three ceṇṭas and the big cymbals ilattālam, but it may include the double-reed shawm kuḻal and the horn kompū. The ceṇṭas are held horizontally and played on both sides with drumsticks as in sandhyā vela. However, the most important side is the vīkan whose deep bass sound leads the dance steps of the oracle. The leader of the ensemble, who plays the vīkan, takes a position one step further from the other musicians. He and the dancer perform facing each other. The drummer stands stable in his position, but at times emphasizes particular sections of the drum compositions by bending forward. The dancer moves back and forth from the drummer performing a series of steps that gradually increase in speed and complexity (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ performed by Kalamandalam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

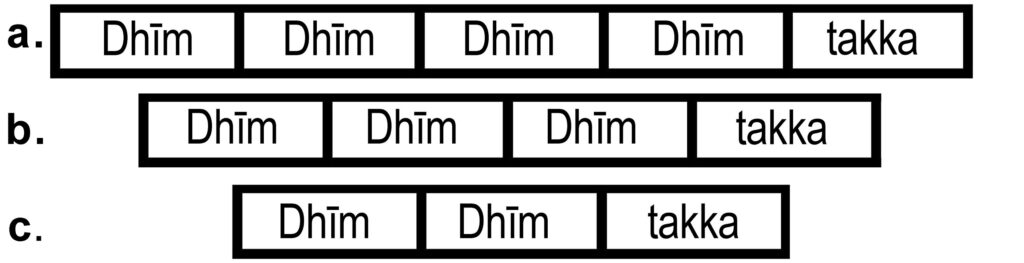

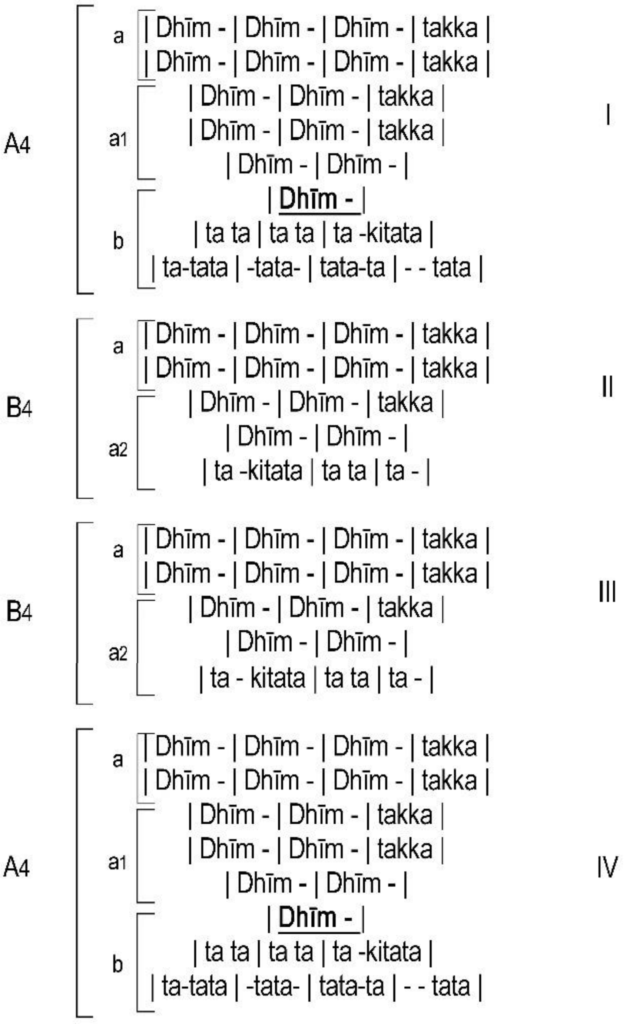

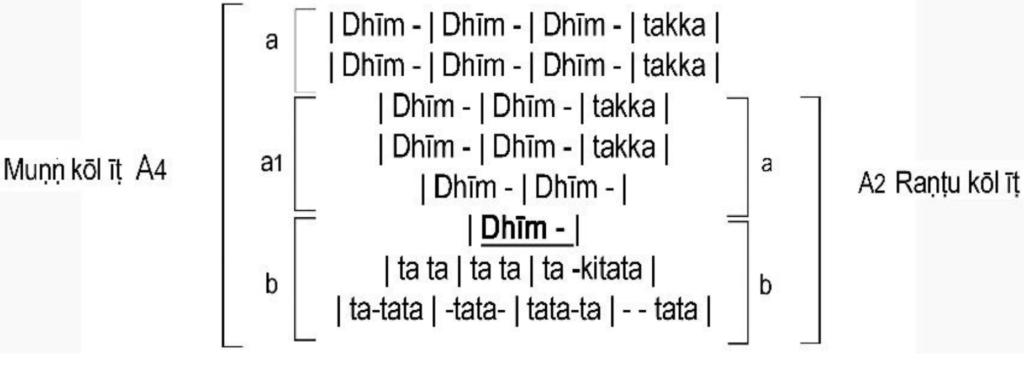

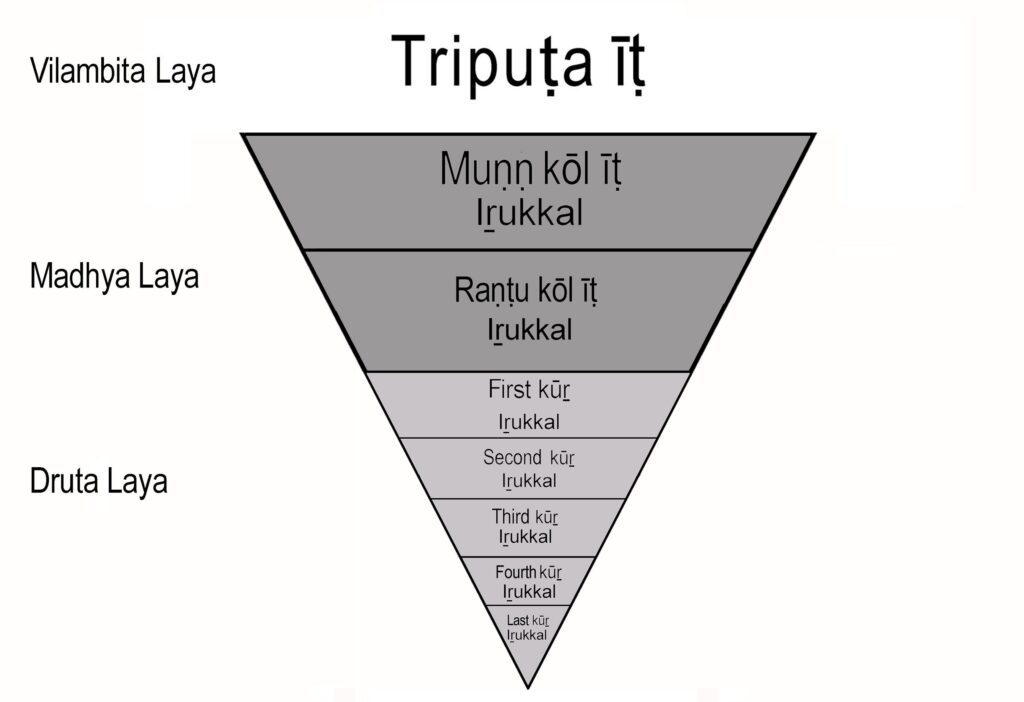

[36] Īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is composed by two parts, the section of the īṭsand the section of the kūṟs. Īṭs and kūṟs are short compositions. The section of the īṭs traditionally includes four pieces called tṛpuṭa īṭ, nālu kōl īṭ, mūnn kōl īṭ, and raṇṭu kōl īṭ. Kōl is a unit of length measurement while nālu, mūnn, and raṇṭu are numbers, four, three, and two, respectively. The name of the īṭs derives from and indicates the number of Dhīms included in the main phrase. Thus, nālu kōl īṭ includes four Dhīms, mūnn kōl īṭ three Dhīms, and raṇṭu kōl īṭ two Dhīms (Example 2). The section of the kūṟs should at least include a sequence of four kūṟs.[34]

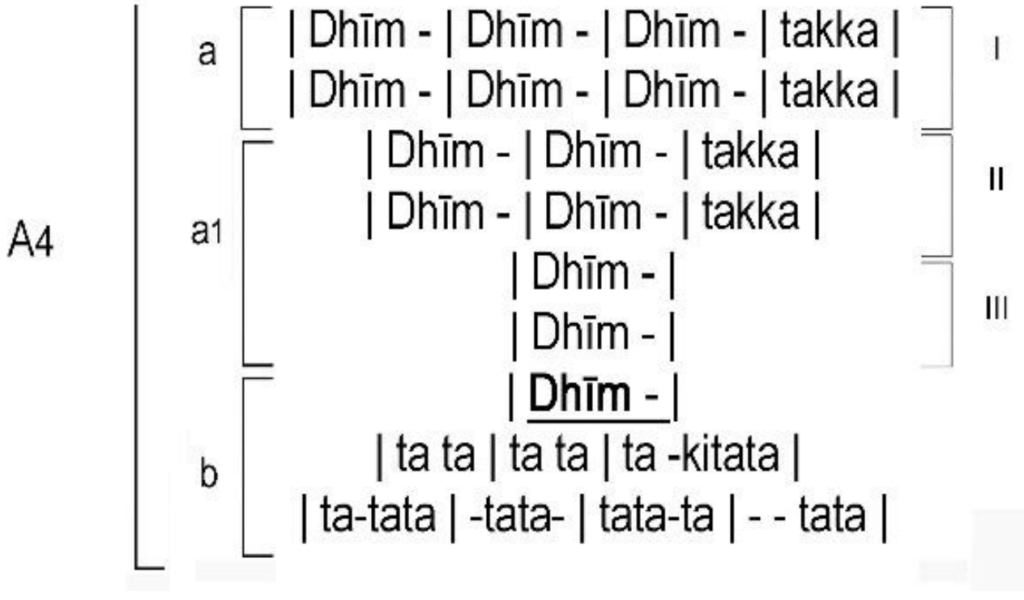

Example 2. Main phrases of a. nālu kōl īṭ, b. mūnn kōl īṭ, c. raṇṭu kōl īṭ.

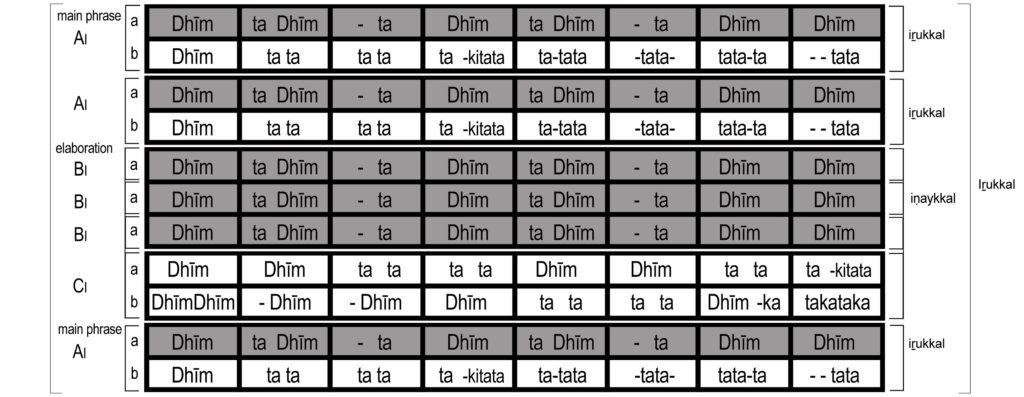

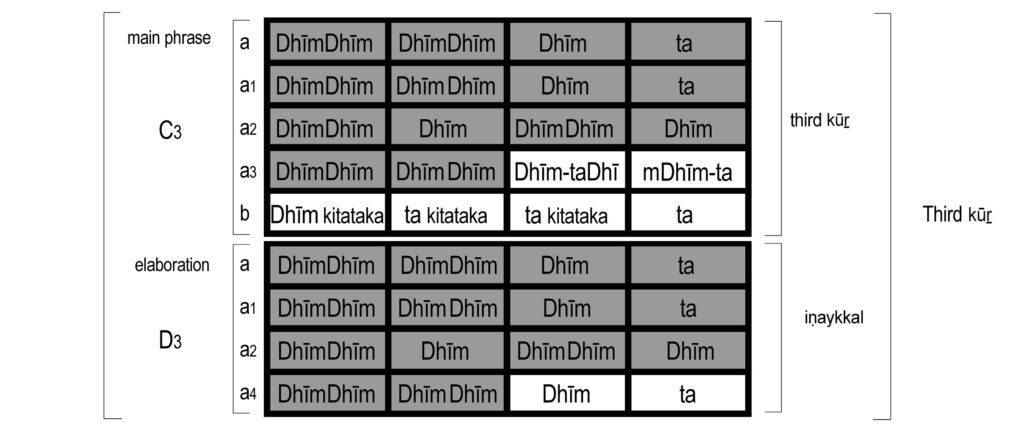

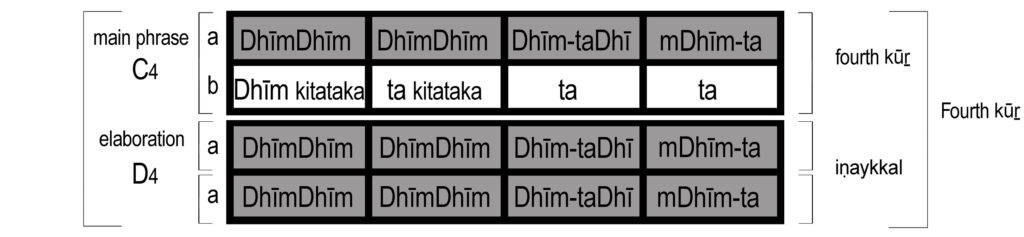

[37] The section of the īṭs has to start with tṛpuṭa īṭ, and the section of the kūṟs with the ‘first kūṟ’. Only the first īṭ is based on tṛpuṭa tāla and has a unique structure; the others are composed in ēka tāla and include three sections: īṭ, iṇaykkal, and iṟukkal. Īṭ may be conceived as the theme. Inakkiyal is an elaboration of the īṭ. The word iṇaykkal means duplicate, and the elaboration consists of repeating twice a section of the īṭ, as it is or in a slightly modified way. Iṟukkal is a composition that is performed as a kind of refrain immediately after every īṭ excluding tṛpuṭa īṭ. Due to these compositional procedures, some phrases are replicated in different sections of the same composition and other compositions. However, the performers conceive them as different from each other and attribute them with unique features on the basis of their relationship with the preceding and following phrases. In other words, according to them, when a phrase is replicated in a different part of the same composition or included in a separate piece, it takes new features and functions. In line with the performer’s perspective, I have labeled these phrases with different letters and numbers. I have attributed the various īṭs and kūṟs with different labels, as follows: Tṛpuṭa īṭ, A7, main phrase, and B7, elaboration; Mūnn kōl īṭ, A4, main phrase, and B4, elaboration; Raṇṭu kōl īṭ, A2, main phrase, and B2, elaboration; Iṟukkal (I stands for Iṟukkal), AI, main phrase, and BI, elaboration; First kūṟ, C1, main phrase, and D1, elaboration; Second kūṟ, C2, main phrase, and D2, elaboration; Third kūṟ, C3, main phrase, and D3, elaboration; Fourth kūṟ, C4, main phrase, and D4, elaboration; Last kūṟ (L stand for last), CL, main phrase, and DL, elaboration; Iṟukkal, CI, main phrase, and DI, elaboration.

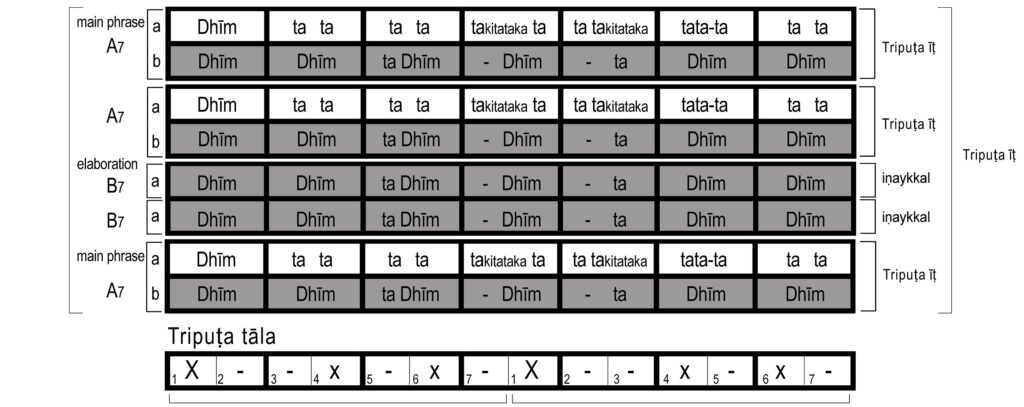

Example 3. Tṛpuṭa īṭ

[38] Tṛpuṭa īṭ is composed by three sections which are īṭ, iṇaykkal,and a short closing formula. It is played at a very slow pace and has a regal character. The steps and the movements performed by the oracle are also slow and dignified. They correspond to the strokes of the drum and mirror the structure of each phrase of the drum compositions. He starts on the first Dhīm of phrase A7a (Example 3, Audio 4) by making a step forward towards the drum with the left foot. On the tas of the second and third beats, he makes four steps backward and, on the strokes ta-kitataka of the fourth beat, stamps the right foot. Then performs a jump raising his right leg at the height of his head while the left leg repeats the movement. This jump is performed numerous times in īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ. It is often connected with trance states and, in that case, is followed by the oracles’ typical shout “iiaahh..”. On the last three beats of phrase A7a the oracle moves three steps forward. Then, on the first Dhīm of phrase A7b, makes a brush with the right foot, extends the right leg forward to ninety degrees, and, on the second Dhīm, brings it back to the starting position with a circular movement of the leg. On the ta, he stomps the floor with the left foot and then performs the same brush and circular leg movement, completing it on the next Dhīm. On the subsequent ta, he stomps the right foot on the floor and performs once again the same brush and movement of the leg. Then, along with the drummer, he first repeats the same steps two times on the iṇaykkal (B7) and then performs the entire sequence of steps associated with phrase A7 once again. Eventually, during a short closing formula played by the drummer, he performs a new jump, which marks the end of tṛpuṭa īṭ. Then, the oracle walks in a circle, and when the drummer introduces the next īṭ, he starts performing the next dance steps. According to tradition, tṛpuṭa īṭ should be followed by nālu kōl īṭ, but it is no longer performed.[35] Thus, at present, mūnn kōl īṭ is played soon after tṛpuṭa īṭ.

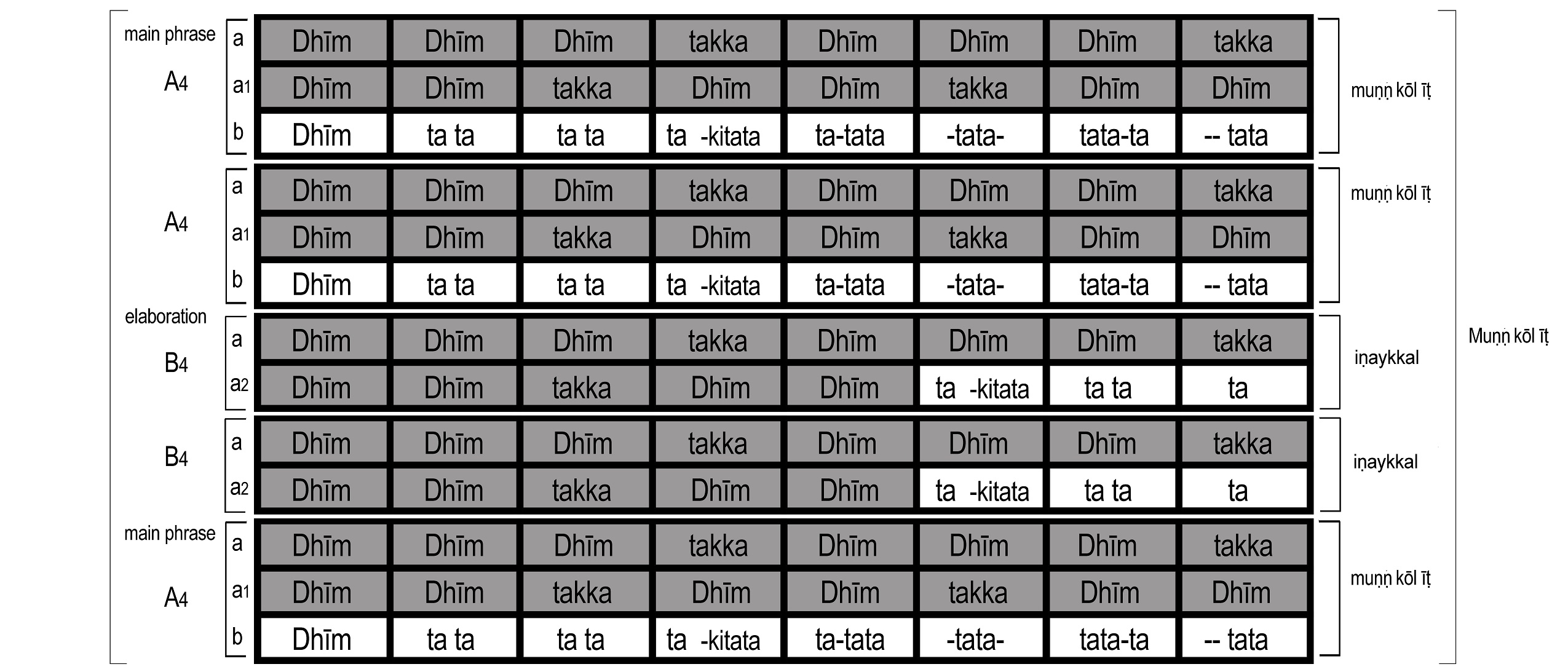

Example 4. Mūnn kōl īṭ.

[39] Mūnn kōl īṭ (Example 4, Audio 5) features a faster pace than the tṛpuṭa īṭ.It is played at almost double its speed,but still, both the composition and the movements of the oracle maintain a dignified martial character. The steps are slightly different from the previous ones, and their variation reflects the piece’s faster pace and the drumbeats’ design. Indeed, while the Dhīms of tṛpuṭa īṭ occupy two beats, those of mūnn kōl īṭ occupy one beat and the steps flow accordingly. Thus, on the first two Dhīms of phrase A4a, instead of beating the floor and performing a circular movement of the legs, the oracle moves twice his left foot and leg forward in the air, and on the third repetition, brings his foot back on the floor. On takka of the third beat, he stamps the floor with the left foot, and on the following four beats, performs the same airy movements of the right foot. On the subsequent Dhīms of phrase A4a1, he performs the same steps with the left, the right, and the left leg again. Then, he repeats the movements of the entire sequence in accordance with the drum composition.

[40] As it has been observed for the sandhyā vela, even the composition of the īṭs is based on numbers. Five and two dominate at the level of the structure, which consists of five sections organized as A A B B A. As the structure of the compositions is created by repeating phrases A and B twice, phrases A and B result from the double repetition of smaller units. Thus, phrase A4 (a+a1) of mūnn kōlīṭ includes two repetitions of its three units, and each one of them is shorter than the previous one, as may be well visualized by notating it as follows:

Example 5. Mūnn kōl īṭ, A4. The main phrases (a+ a1+b) and the three units (I, II, II) of A4 (a+a1).

[41] This compositional procedure builds the phrase in such a way that it tends towards the Dhīm of phrase A4b—underlined and highlighted in bold—and the directional effect is further emphasized by the fact that the resonating Dhīm is followed by a sequence of closed tas. Phrase A4b is a crucial element of the īṭ section, both in terms of drumming and dance. Indeed, it is performed twelve times across mūnn kōlīṭ (A4b), raṇṭu kōl īṭ (A2b), and iṟukkal (AIb).

[42] The same compositional procedure is replicated in the iṇaykkal where phrase B4a is identical to A4a and phrase B4a2 is a slightly different version of A4a1. However, in this case, the resolution of the tension is delayed by the last three-beats closing formula |ta -kitata| ta ta | ta| in phrase B4a2 which replaces phrase A4b. The absence of the resonating strokes in this closing formula increases the tension towards the next Dhīm and the expectation of its arrival. Indeed, the repetition of the phrase B4 followed by phrase A4 amplifies and empowers the same phrases, and when the new Dhīm of phrase A4b (IV)—underlined and highlighted in bold—is finally reached its releasing effect appears even more powerful (Example 6). Interestingly, the same process is manifested in the steps of the oracle, which find their completion and goal in the jump performed on the Dhīm—underlined and highlighted in bold—of the last phrase A4b (IV).

Example 6. Mūnn kōl īṭ, alternative notation.

[43] The process activated by the described procedure is further applied and even enhanced in the iṟukkal, which is a piece based on the same rules and structure of the īṭs and includes phrase A4b (AIb) as well. Its unique factors are the fact that the elaboration triplicates the first part of the main phrase BIa—instead of duplicating it—and that it includes as a closing formula a new phrase (CI) of sixteen beats (Example 7, Audio 6). AIa, the main phrase of AI, is characterized by a distinctive swing resulting from a sequence of taDhīm– strokes. The threefold repetition of phrase BIa in the elaboration (BI) and the sixteen beats closing formula CI, which leads back to phrase AIa, further amplify the effect of tension and the connected release on the Dhīm of phrase AIb which coincides with the last jump of the oracle in the mūnn kōlīṭ section.

Example 7. Iṟukkal.

Example 8. Raṇṭu kōl īṭ.

[44] The entire īṭ sequence evolves into progressively simpler and shorter phrases and a faster pace. Raṇṭu kōl īṭ (Example 8, Audio 7) is clearly connected with mūnn kōlīṭ. In fact, it is embedded into mūnn kōlīṭ. Phrase A2a of raṇṭu kōl īṭ is identical to A4a1, the second phrase of mūnn kōlīṭ (A4). The relationship between phrases A4a1 and A2a may be visualized in the following example:

Example 9. Mūnn kōl īṭ (A4) and Raṇṭu kōl īṭ (A2) relationship.

[45] Excluding tṛpuṭa īṭ, which is set on the seven beats tṛpuṭa tāla, the first part of the main phrases (A4a, A2a, AIa) of the īṭs and the iṟukkal, which are in ēka tāla, are composed of sequences of eight beats including patterns of six Dhīms. A4 (a+a1) of mūnn kōl īṭ lasts sixteen beats and hence includes 6+6 Dhīms, phrases A2a of raṇṭu kōl īṭ and AIa of iṟukkal last eight beats and include 6 Dhīms. By contrast, the second part of the main phrases (A4b, A2b, and AIb) – which is identical for all of them – is based on the closed stroke ta and includes only one Dhīm. Thus, A4 (a+a1+b) comprises a pattern of 6+6+1 Dhīms, while A2 (a+b) of raṇṭu kōl īṭ and AI (a+b) of iṟukkal eachcomprise a pattern of 6+1 Dhīms. Furthermore, the analysis of the patterns of six Dhīms shows that they are designed in progressively shorter phrases composed of a decreasing number of Dhīms. In phrase A4 (a+a1) we find a four-beat pattern of 3 Dhīms –|Dhīm – | Dhīm – | Dhīm – | takka |– repeated twice and followed by a three-beat pattern of 2 Dhīms –| Dhīm – | Dhīm – | takka |– and a two-beat closing formula of two Dhīms –| Dhīm – | Dhīm – |. In phrase A2 (a), we find the previous three-beat pattern of 2 Dhīms –| Dhīm – | Dhīm – | takka |– followed by the same two-beat closing formula. In phrase AI (a), just a one-and-a-half-beat pattern including 1 Dhīm –|Dhīm – | ta –, repeated four times to cover six beats, followed by the two-beat closing formula. Interestingly, the compositional procedure so far analyzed is emphasized by the fact that each īṭ is played faster than the previous one. Thus, while tṛpuṭa īṭ is played at a slow and dignified pace raṇṭu kōl īṭ and the last iṟukkal are played at a fast pace.

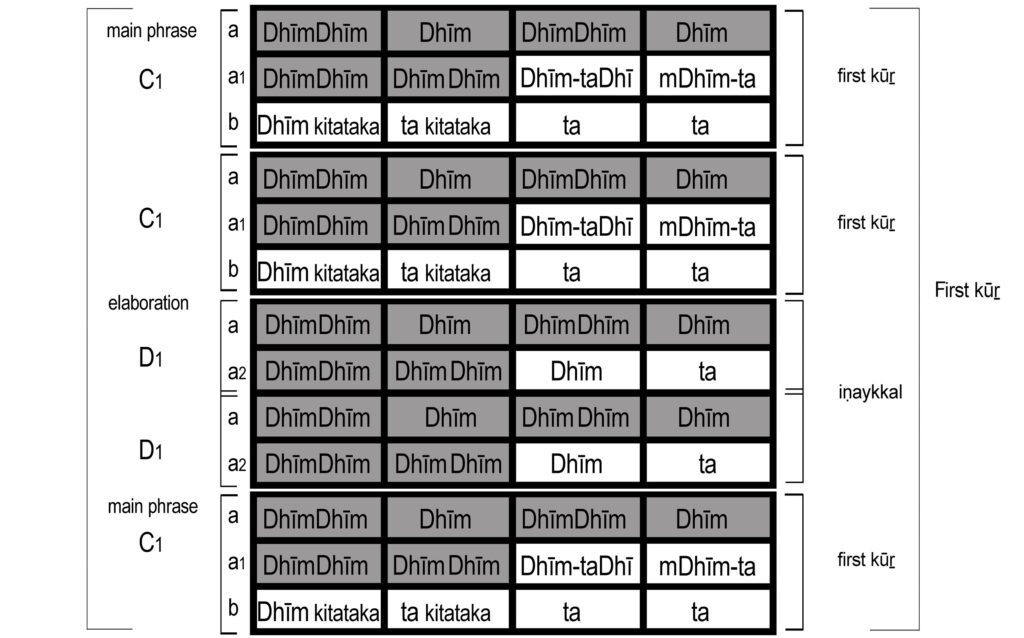

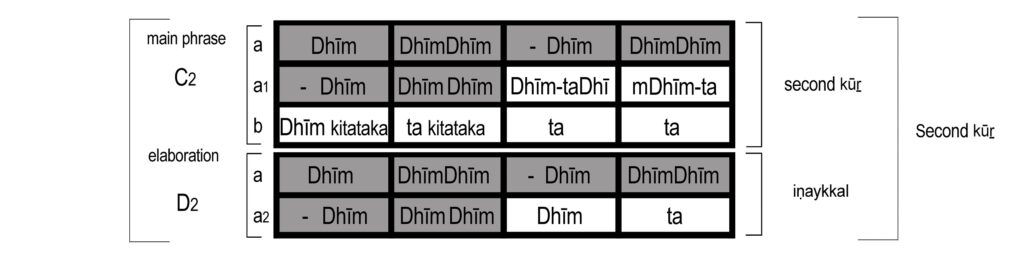

[46] The section of the īṭs ends with the last jump of the oracle in the iṟukkal. Soon after that, the drummers increase the pace of their music, and the main drummer starts playing the first kūṟ (Example 10) followed by the iṟukkal (Example 15) (Audio 8). It is an important piece that marks the beginning of the second part of the ritual dance and, as with tṛpuṭa īṭ, it cannot be omitted or replaced. Its main phrase (C1) is, as it has been seen with the īṭs, composed by the duplication of short units –|DhīmDhīm | Dhīm – | and | DhīmDhīm |– which leads to phrase C1b. It is analogous to phrases A4b, A2b, and AIb of the īṭ section and equally significant, since its Dhīm marks the climax of the composition and the jump of the oracle. It is played several times. The oracle performs steps similar to the previous ones but at a faster pace and much more vigorous and energetic way. He does not move forward and backward as in phrase A4b, but remains on the same spot moving the legs forward in the air and then back again according to the Dhīms of phrases C1a and C1a1. Indeed, while in the previous section one Dhīm occupied one beat, in this section Dhīms often occupy half a beat, and appear in sequences of two or four. By contrast, the tas, which were almost always played in couples as takkas, in this section last one beat and are marked by a heavy stomping of the feet of the oracle.

Example 10. First kūṟ.

[47] The other kūṟs—which I notate in the following examples along with their iṇaykkal but without repetitions—follow the same structure and end with the same iṟukkal (Example 15). They are interconnected and share various phrases. Interestingly, while in the section of the īṭs the numbers of Dhīms and tas are relatively balanced, Dhīms dominate in the section of the kūṟs, and this feature charges the drumming and the dance with a kind of energy and excitement that are absent in the previous compositions.

[48] The second kūṟ is very similar to the first, but features a more geometrical composition of the Dhīms, which are arranged in a sequence of two, three, and four units (Example 11 Audio 9). The third kūṟ (Example 12, Audio 10) includes phrases D1a2, C1a, and C1b of the first kūṟ and the fourth is based on phrase C1a1 (Example 13, Audio 11). The last kūṟ is composed by phrase C1a and the entire second kūṟ joined by phrase Cla1, which is, in its turn, a variation of phrase C1a (Example 14, Video 1).

Example 11. Second kūṟ

Example 12. Third kūṟ.

Example 13. Fourth kūṟ.

Example 14. Last kūṟ.

Example 15. Kūṟ iṟukkal.

[49] Each kūṟ is faster than the previous, and the last one is the fastest. Thus, the process performed by īṭum kūṟuṃ, as the performers also acknowledge it, is one of continuous acceleration at the levels of both the general structure and internal phrases.[36] The entire procedure may be rendered visually as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Visual rendition of the structure of īṭum kūṟuṃ.

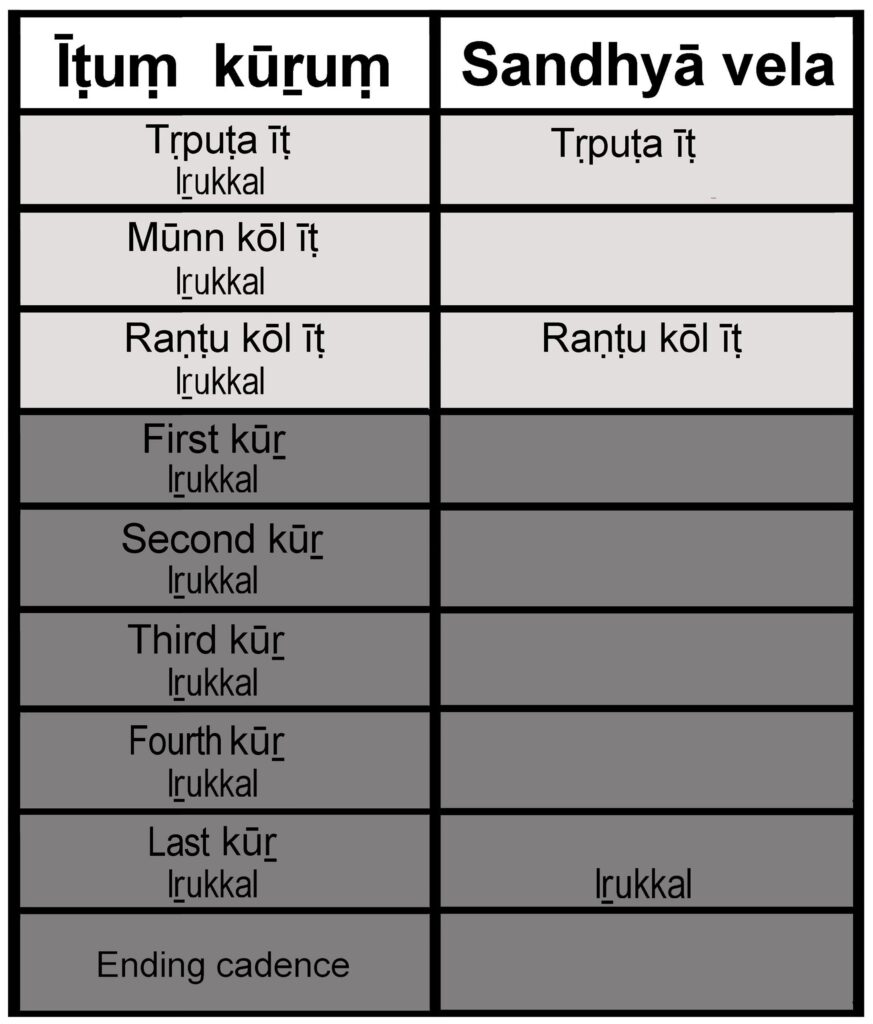

[50] Īṭs and kūṟs (together known as īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ) are composed with the same strokes of sandhyā vela and share the structure of its sections. In fact, we may say that sandhyā vela is the essence of īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ. In the case ofthe Thrittala Poṭuvāl tradition, which I analyze in this article, the sandhyā vela is composed of three parts that correspond to different compositions of the īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ. Indeed, the first part based on tṛpuṭa tāla is a very slow and slightly varied version of tṛpuṭa īṭ, the middle section is precisely the raṇṭukōl īṭ, and the final part is the iṟukkal of the kūṟ section and the last piece of the īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ (Table 1).

[51] However, as has been pointed out already, while there are various versions of sandhyā vela according to different traditions, the strokes and syllables (vāyattāri) of the īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ have been transmitted in almost identical form to members of different communities.[37] Thus, Teyyampāṭi Nambyārs, Teyyampāṭikuruppus, Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, Mārārs and Poṭuvāls perform the same composition. This clearly shows the importance of the īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ, which the performers often associate with marappāṇi,[38] the most sacred class of compositions played by Mārār and Poṭuvāl musicians in Brahmanical temples.[39] Marappāṇis are performed to invoke the deity during festivals and other special occasions. They are exclusively transmitted to the few members of the communities who wish to learn them and are ready to obey the commitments and risks they involve. Indeed, during festivals, the main performer of marappāṇi is allowed to eat only selected food, and has to fast for many hours before the beginning of the ritual performance. Most importantly, he has to play it without mistakes since a wrong performance might be punished by the deity with his own death.[40] Interestingly, īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is specifically connected to kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu, and it is not learnt by every Mārār or Poṭuvāl musician, while sandhyā vela, although important, is part of the repertoire, which is generally transmitted to all of them. With relation to this aspect, a knowledgeable Mārār musician from central Kerala confidentially told me that, according to him, the sandhyā vela as it is presently played in his tradition had been transmitted wrongly since it does not include the section in tṛpuṭa tāla. These features, along with others that cannot be argued in this essay, suggest that īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is the source of the sandhyā vela.

Table 1. The structures ofīṭuṃ kūṟuṃ and sandhyā vela.

Kaḷapradakṣiṇa

[52] At the end of the īṭum kūṟuṃ the drum ensemble, the oracle with his sword, and the priest carrying the other sword move in procession to the space where the kaḷam has been drawn. There, another sequence of dance steps is started by the oracle, who, in this performance, is the leading figure. He will decide the steps and the drummers will play accordingly. The musicians who were playing the ceṇṭa horizontally rotate it to play the high-pitched side or uruṭṭu ceṇṭa. The main drummer turns it on the other side and plays the vīkan ceṇṭa, which remains the drum giving the beats to the steps of the oracle.

[53] Kaḷapradakṣiṇa, as pointed out by the name itself, is a dance based on circumambulations (pradakṣiṇas) of the kaḷam. It is rather schematic, and the variation element is provided by rhythm. The oracle performs two types of movements: 1) a clockwise rotation of the entire body on the same spot, performed by moving alternately the right foot front and back and then the left foot front and back towards the eight directions of the space (Figure 11); 2) the circumambulation of the kaḷam by performing different steps based on different tālas (Figure 12).

Figure 11. Kaḷapradakṣiṇa performed by Kalamandalam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu: rotation on the spot. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Figure 12. Kaḷapradakṣiṇa performed by Kalamandalam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu: circumambulation of the kaḷam. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

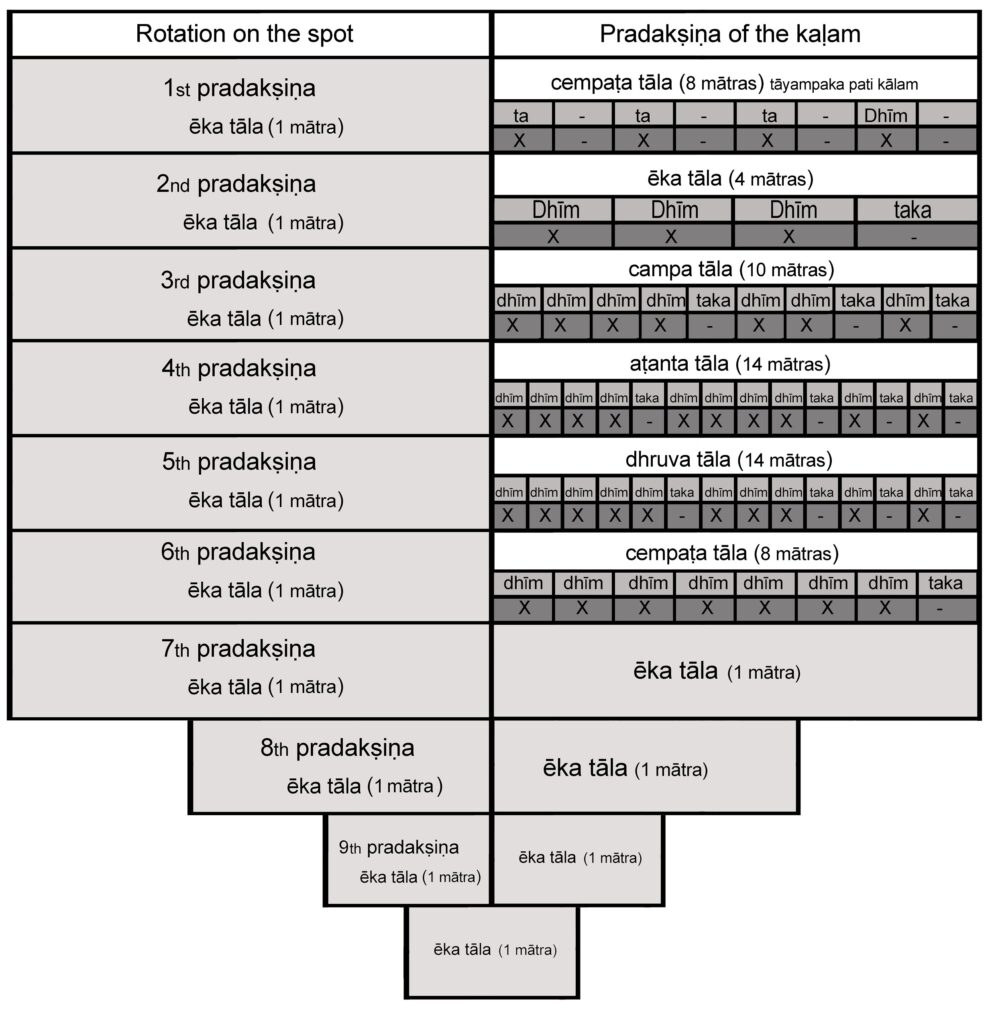

[54] The whole sequence starts from the spot on the west side of the kaḷam corresponding to the feet of the deity. In that position, the oracle starts rotating on the spot—keeping his own spinal cord as axis—while creating a kind of an eight points star with the movements of the feet (Figure 11). Having completed one full rotation, he circumambulates the kaḷam in clockwise direction seven, nine, or eleven times. While the rotation on the spot is always performed in ēka tāla, every time at an increased speed, the circumambulations of the kaḷam are completed by performing different steps based on different tālas whose pace is also gradually increased. As for the īṭum kūṟuṃ, the sequence may change according to the needs and habits of the performers. Kalamandalam Haridas Kallattakuruppu described a sequence as follows. The first and the second pradakṣiṇas are supported by campaṭa tāla and then ēka tāla, played in four beats. The third pradakṣiṇa is performed on campa tāla, a cycle of ten beats. The fourth pradakṣiṇa of the kaḷam is danced to the fourteen-beat aṭanṭa tāla, the fifth to the fourteen-beat dhruva tāla, the sixth on the eight-beat campaṭa tāla. The last pradakṣiṇas are performed in ēka tāla, and the oracle increases the pace until he enters a state of trance, shouts iiaahh…. and makes a jump (Video 2). The whole sequence may be synthesized as in Table 2.

Table 2. Kaḷapradakṣiṇa. The sequence of dance steps, circumambulations of the kaḷam and tālas.

[55] At the end of the dances, the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu places the sword near the wooden stool in the kaḷam and retires while a Brahmin performs a pūjā for the kaḷam and a Mārār or a Poṭuvāl, sings compositions in the sōpāna saṅgīta style to the accompaniment of the hourglass drum iṭakka (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Brahmin performing kaḷam pūjā for the kaḷam of Asuramahākālan, Śiva Mahādeva

temple, Thrittala. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Ammaṉachāya

[56] Kaḷam pūjā is followed by a new section of songs called ammaṉachāya (the middle part). It includes antippāṭṭu (evening song), pādādikēśa (from feet to hair), and kēśādipādam (from hair to feet), which describe the manifestation of the goddess, her numerous arms, the weapons she holds, the gestures she makes and the features of every part of her body, and pāṭivekkal (sing and offer), which narrates the war between Bhadrakālī and Dārika. A new stuti, a song praising Bhadrakālī along with other deities, brings the singing of the pāṭṭu to an end. The songs are based on tṛpuṭa (7 beats), pañcāri (six beats), ēka (1 beat), and aṭanta tāla (14 beats).

Figure 14. Kalamandalam Haridas singing ammaṉachāya along with two assistants. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Figure 15. Kalamandalam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu performing the tiriyuḻiccal. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Tiriyuḻiccal

[57] When the pūjā is over, the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu oracle, holding the sword, comes back to the kaḷam and performs the tiriyuḻiccal, the waving of lighted wicks, an offering to the Sapta Mātṛkas (Seven Mothers) and the Aṣṭa Dikpālas (Eight Guardians of the Directions) (see § 17). He puts rice, flowers, nine wicks, and a coconut on a plate, lights nine wicks from the Gaṇapati lamp, and performs three circumambulations of the kaḷam. He then places the wicks on the eight corners and the last one at the feet of the image. The entire ritual is supported by a vīkan ceṇṭa playing at a slow pace a phrase in the eight-beat campaṭa tāla.

[58] Once he has completed this ritual, in order to release the energy of the deity from the kaḷam into the universe, he takes some rice and throws it toward the ceiling of the maṇḍapam. Then he starts erasing the kaḷam by means of dance steps and by dragging the stool over it. Then, shouting iiaahh… he starts proffering the oracle. Then, he distributes the powder of the kaḷam as consecrated food (prasāda), rolls up the red silken cloth from the ceiling of the maṇḍapam, and gives it back to the organizer.

Teṅṅāryericcal

[59] In the case of Vēṭṭaykkorumakanand the other male deities, the oracle has to perform another ritual called teṅṅāryericcal, ‘throwing of coconuts.’ In this ritual, sitting cross-legged on a seat of coconuts, he breaks all these coconuts—whose number varies according to the wealth of the organizer—by throwing them by alternate hands on a stone in time with the rhythm of the mēḷam.

DANCING IN THE BATTLEFIELD

[60] The contemporary kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu in the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu tradition is a sequence of rituals performed by three different communities: the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, who play the major role since they draw the kaḷam, sing the songs and perform as oracles; the Brahmins, who perform the pūjās to the kaḷam; and the Mārārs or the Poṭuvāls, who support and complete the rituals of both the other groups. Each one of these communities has contributed to the making of the contemporary form with their practices and ideas. While the performing specialties and duties of these groups are clearly distinguished, the ideas behind their respective rituals are now blurred, and obscured by the authority of the Brahmanical view. The Brahmanical perspective is clearly presented in an article published on the site Namboothiri Website Thrust. It maintains that Vēṭṭaykkorumakan pāṭṭu, but it applies to any kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu, is a ritual mostly performed by Nampūtiris in order to get peace of mind and that “symbolically, the various elements in the story can be related, through Yoga Śāstras and Kuṇḍalinī, to the state and workings of the mind.”[41] From this point of view, kaḷapradakṣiṇa is the crucial part of the ritual, since the circumambulations of the kaḷam completed by the oracle are interpreted as symbolically representing the steps in the ascent of Kuṇḍalinī—the divine energy imagined as a snake coiled at the base of the spine of the human beings—through the cakras. The article also tells that the ritual breaking of coconuts is meant to eliminate the troubles and problems of the family.

[61] Another interesting Brahmanical point of view is presented by Arikkara Girish Nampūtiri, chief priest at Sree Navamukunda temple at Thirunavaya, who maintains that all the main rituals performed in Brahmanical temples have been incorporated into the procedure of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu centuries ago, but the practice was disrupted or perished due to the lack of successors. In his view, the story of the priests and the helper drawing the picture of Bhadrakālī on a stone is the resuscitation of the ritual after centuries of dormancy (Haridasan 2019, 19:00-21:00).

[62] Interpretations that suggest connections between kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu and the main rituals of Brahmanical temples are also presented by some kaḷameḻuttu performers. According to Manikandan Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu, īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ may be compared to marappāṇi because both are so important that they do not allow any mistake in their performance. He describes īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ as a dance of joy, expressing the happiness of a hunter coming back from the hunt with a prey. Further, he establishes an analogy between the procession of the oracle with the sword in mullakkal pāṭṭu and the mock hunt (paḷḷiveṭṭa) performed in Brahmanical temples during their most important festival (utsavas) (Haridasan 2019, 89:50). Furthermore, he explains the breaking of coconut as an offering of elixir (amṛta), symbolized by coconut water, to gods and distinguishes it from blood (guruti) offered to the goddess. He also adds that it represents the breaking of all curses and sins of the village in front of the deity (Haridasan 2019, 103:51). Kalamandalam Haridas Kallaṯṯakuṟuppu reported a belief according to which kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu is performed to purify the society from negative feelings. He also proposed the interpretation of īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ as a hunter dance of joy and added that the animals the oracle hunts may be thought to be the negative human emotions that he puts into the kaḷam and destroys through his dance.[42]

[63] If we compare the worship procedure in Brahmanical temples and the sequence of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu, we find a number of aspects that overlap. This is unsurprising, considering that even Brahmanical temples follow a Tantric ritual procedure (Pacciolla 2021b; Ajithan 2018). However, simple observation shows that the sword is the dominant element of the kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu. Placed on the stool, the sword is at the center of the ritual from the very beginning, and pūjās, music, and dances are performed to empower it. The sword in the hand of the oracle destroys the kaḷam and is the last place from which the power of the goddess or other gods is released at the end of the ritual. This striking importance of the sword highlights the connection of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu with Śākta temples and strongly suggests that it was performed to worship and empower Bhadrakālī and similar deities in the form of a sword but also to empower the king to become invincible in battle (Sanderson 2007, 184 and 288–290; Ajithan 2015, 8). In fact, as has been said, kings were the main patrons of Śākta temples, which hosted their family deities. The importance of the sword for the warriors does not need to be explained. However, it may be exemplified in the veneration of the Zamorines for the sword which they received from the last Cēra king as a symbol of over lordship and in the role of the sword in their rituals as representative of the family goddess and her power (Śakti) (Narayanan 2018; Ayyar 1938).

[64] In Śākta perspective, the sword, the kaḷam, and the oracle are embodiments of the goddess and have to be empowered, and kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu songs, drum compositions, and pūjās are the source and the vehicles of power (Śakti) (Sanderson 2007; Ajithan 2015; Sarma 2015; Gentes 1992; Pacciolla forthcoming).[43] Īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is a dance through which the dancer incorporates the power of the sword, and since the sword and its power are Bhadrakālī,[44] the goddess of victory in the battlefield, it is a dance evoking the goddess in the body of the dancer.[45] It is a representation of Bhadrakālī as an emblem of victory. We have already pointed out that in īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ the dancer is guided by the drum. We may also say that the movements of the dancer originate from the drum and move back to it and that they are also energized by its voice and phrases. In a similar way, it is drumming that activates Śakti, the energy of the goddess, in the sword.[46] In other words, the power of the sword is embedded in the rhythm produced by the drum.

[65] The importance of the drum and its role in kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu is clearly pointed out in a line of the invocation song (vaḻinaṭa), where Bhadrakālī is defined as the one “who comes with the sound of drums (koṭṭu).” We have seen that the sandhyā vēla is performed to summon the goddess and that, along with the invocation sung by the Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus, it marks every juncture of the making of the kaḷam. We have also seen that the īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is an enlarged form of the sandhyā vela, and it is played with the dance of the oracle. Thus, we may suggest that the sandhyā vēla is played to invoke the goddess in the sword and in the kaḷam while the īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is performed to summon her in the body of the oracle.

[66] At the end of īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ, the oracle has embodied the goddess and moves in royal procession towards the kaḷam to perform the kaḷapradakṣiṇa. The analysis of the performance of kaḷapradakṣiṇa suggests that it enacts, by means of rhythmic cycles (tālas) and dance steps, the process of identification of the deity embodied in the oracle with the deity embedded in the kaḷam. We have seen that the oracle performs two main movements, the rotation on a single spot on his own spinal cord, which is always done in ēka tāla, and the pradakṣiṇas of the kaḷam, which evolves through different tālas. If we consider the movements on the spot as representative of the goddess invoked in the body of the oracle, and those around the kaḷam as representative of different states of being or cakras—as suggested by Brahmins (see § 60)—of the goddess invoked into it, we see that rhythms and dance steps tend to converge into the rhythmic climax which is represented by the ēka tāla (Table 2). Both movements evolve from a slow pace to very fast steps and meet and join in a fast ēka tāla in which the oracle dances for as many pradakṣiṇas as he needs to complete his identification with the deity and enter into trance. Thus, I maintain that we may interpret the kaḷapradakṣiṇa as a ritual through which the deity in the oracle merges with the deity in the kaḷam and understand the very fast ēka tāla as a sonic and energetic representation of the power (Śakti) of the deity.

[67] Drumming represents power, and the gods’ relationship with tālas is a significant aspect of the ritual. The tālas, which literally dominate the entire ritual, are tṛpuṭa and ēka tāla. The songs are almost exclusively based on seven-beat tṛpuṭa and one-beat ēkatāla; pāṇṭi mēḷam, which accompanies the procession of the sword and the oracle, is based on aṭanta tāla, a fourteen-beat tāla, which progressively reduces to seven beats and ends in ēkatāla; sandhyā vela and īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ are composed on tṛpuṭa and ēkatālas. Tṛpuṭa is considered a tāla expressing vigor and valor and, along with other seven beats tālas, it is a tāla associated with the worship of Śiva and related deities.[47] Seven is the number of Bhadrakālī and the Mothers (Sapta Mātṛkas) and they are worshipped by playing compositions in tṛpuṭa,[48] while the eight-beat campaṭatāla is connected with the eight regents of space (Aṣṭa Dikpālas) (Pacciolla forthcoming). The importance of the number seven is also highlighted by the presence of seven Dhīms in the main phrases of the compositions of sandhyā vela and īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ, and in the forty-nine Dhīms in the iṟukkals of both īṭ and kūṟ sections. This is an interesting aspect, since, according to Mārārs and Poṭuvāls, the numbers associated with specific strokes in important ritual compositions in their repertoire hide a symbolic meaning.[49] Ēkatāla is the father of all the tālas and the culmination of every composition of the Mārārs and Poṭuvāls. Each composition ends in ēkatāla, which is the musical climax and its most energetic part.[50] Accordingly, the manifestation of power is conveyed aesthetically by proceeding from slow, elegant, and powerful drum compositions and dance steps to very fast drumming and movements evoking the fury of the fight in the battlefield.

[68] Performers define īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ as a furious or tāṇḍava dance. The oracle dances holding the sword in the right hand while the left arm is elegantly stretched on the left side of the body and kept inactive. In fact, the dance posture of the oracle is strongly reminiscent of the Tāṇḍava dances of Śiva (Figure 16) and the sculptures of Kṛṣṇa dancing over the head of a subjugated serpent Kāliya, and bears a striking similarity with the dance posture of the late 10th century Chola bronze of Kṛṣṇa dancing on a lotus held at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (Figure 17).[51]

Figure 16. Śiva dancing over the body of a subjugated demon. Śiva temple at Gangaikonda Cholapuram, Tamil Nadu. Photo by Paolo Pacciolla.

Figure 17. Kṛṣṇa dancing on a lotus, 10th century, Chola Dynasty, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Accession number 54.2850.

[69] The fact that Śiva and Kṛṣṇa dance stomping their feet over the body of their enemies helps us understand, once again, īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ as a dance celebrating victory. Indeed, while in the īṭ section and particularly in tṛpuṭa īṭ, the dancer moves slowly and with elegance and has a regal mood and pace, his dance steps become very fast and vigorous in the kūṟ section. In this section, the pace of drum compositions increases significantly and the leg movements, which follow the beats of the vīkan ceṇṭa according to precise rules, become faster and mostly execute movements in the air. The strong relationship of the drummer with the dancer again reminds one of the iconographies of Śiva Nāṭarāja, king of dancers, and the myths narrating that the drum energizes the god and, at the same time, keeps him under its control (Pacciolla 2020), as in īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ the drummer controls the dancer.

[70] As already pointed out, at present, such an important ritual role is performed by Mārārs or Poṭuvāls, who maintain a high position even in Brahmanical temples. Contemporary Kallaṯṯakuṟuppus do not play drums and we can see that it was not their duty even at the time of the Brahmin appropriation of kaḷameḻuttu pāṭṭu since, according to the story (see § 17), a Mārār was performing there.

[71] If īṭuṃ kūṟuṃ is a dance simulating a battle and evoking victory, even the kaḷapradakṣiṇa enacts a battle and leads to the victory dance in which the oracle erases the kaḷam with his feet and the stool. In order to see the connection between kaḷapradakṣiṇa and a battle, we have to consider that the word kaḷam means also battlefield (Choondal 1978, 8; Heitelbetel 1988, 167), and the erasing of the figure is in a sense a killing. This aspect is highlighted by Caldwell, who writes that according to Krishnan Kutty Mārār, an expert kaḷam artist interviewed by her, in earlier times a close relationship existed between the kaḷam tradition and martial arts, and the esoteric military imagery is expressed in the kaḷam by the goddess holding the bloody decapitated head of Dārika in her hand (Caldwell 2001, 97; Heitelbetel 1988, 170–182). A martial feeling of valor and might also permeates the kaḷapradakṣiṇa, where the oracle performs heavy and vigorous martial dance steps marked by the vīkan ceṇṭa and accompanied by the drum ensemble.