Rao

Analytical Approaches to Music of South Asia, Volume 1 (2023)

Suḷādi Songs of Haridāsa Composers

Arati Rao

Author information: Department of Performing Arts at JAIN (Deemed-to-be) University (email: aratirao71@gmail.com).

Received June 1, 2022; Accepted pending revisions September 25, 2022; Revised version received July 12, 2023; Published December 29, 2023.

Abstract: Suḷādi songs of Vaiṣṇava Haridāsa composers of South India of the sixteenth to the nineteenth century have a unique structure, with sections being set to different tālas (metric cycles). Suḷādi are not part of the repertoires in South Indian art music of the present day. Some manuscripts with musical notations of suḷādi from the Thanjavur Maharaja Serfoji’s Saraswathi Mahal Library (TMSSML) in Thanjavur, South India have been taken up for study by the present author in the last few years. The findings of the study give insights into the musical form, rāgas(musical modes) and tālas of the suḷādi songs. These songs appear to have a connection with other song types defined in the Caturdaṇḍīprakāśikā, a musical treatise of the seventeenth century. The musical form as seen in the notations displays some features common to sālagasūḍa prabandha described in Indian musical treatises of the medieval period. The rāga features seen in the suḷādi notations are largely in conformance with the South Indian musical treatises Rāgalakṣaṇamu and Saṅgītasārāmṛta of the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries. The tālas of the suḷādi have been in practice in South Indian art music in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries and have been used in beginners’ exercises as well as gīta, prabandha, kṛti, and varṇam songs. The structures of the tāla seen in the suḷādi notations appear to be close to the features of the tālas seen in present-day South Indian art music. Further examination of suḷādis along with gīta, prabandha, ālāpa, and ṭhāya songs, and musicological descriptions would be valuable for the study of the evolution of South Indian art music in the medieval and early modern period.

Keywords: suḷādi; suḷādi tāla; Haridāsa songs; Caturdaṇḍī; South India

© 2023 by the author. Users may read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of this article without requesting permission. When distributing, (1) the author of the article and the name, volume, issue, and year of the journal must be identified clearly; (2) no portion of the article, including audio, video, or other accompanying media, may be used for commercial purposes; and (3) no portion of the article or any of its accompanying media may be modified, transformed, built upon, sampled, remixed, or separated from the rest of the article.

To view an image (figure, example, or table) at its original size, right-click (or control-click) on it, and select “Open image in new tab.” To download an image or a video, select “Save image as” or “Save link as” instead. (The latter can be helpful when accessing a longer video, which might load slowly.)

Click here to read the PDF version of the article

[1] Suḷādi songs are devotional musical compositions in the Kannada language of Haridāsa saints of South India. The first known suḷādis were composed in the fifteenth century. Suḷadis have several sections set to different tālas (metric cycles). These songs are not part of the repertoires of South Indian art music (Karnatak Music) in the present day. However, they seem to occupy an important place in South Indian art music in the late medieval and early modern period of South Indian musical history, as evidenced by references to suḷādis in the musical treatises of the seventeenth and eighteenth century: Rāgalakṣaṇamu of Śāhajī and Saṅgītasārāmṛta of Tulaja. Passages of suḷādi notations have been cited in these texts as rāga exemplars.[1] Tulaja also gives a detailed description of a suḷādi by Purandara Dāsa, “Hasugaḷa kareva dhvani,” presenting the argument that suḷādi was equivalent to the song type sālagasūḍa prabandha, prevalent in medieval Indian music (SSA 12.150–153).

[2] Heterometric songs (songs having more than one tāla) are not new to music in South Asia. Examples can be found in the Sufi-Islamic song-type qalbāna, the Sikh Gurubānī repertoire, temple music in Vrindāban, UP, India, and the gvāra songs of Nepal (Widdess 2019). Apart from these, there are tālamālikas in present-day South Indian art music where each section is set to a different tāla. However, these are not commonly performed. Suḷādis appear to be similar to other heterometric songs that are described by Widdess as “through composed,” that is, sections are not repeated but all sections are performed in a linear sequence (2019). Each section of a suḷādi is set to a single tāla; it may have an internal refrain, and a mudra (nom de plume of the author/composer). It is therefore likely that a suḷādi comprises the amalgamation of a sequence of separate songs in different tālas.

[3] There does not seem to be a living musical tradition of the suḷādis, as shall be discussed subsequently. Suḷādi songs can be reconstructed from two sources—suḷādi lyrics from published sources, and suḷādi melodies from musical notations. In the early twentieth century, Haridāsa scholars from the state of Karnataka in South India published several suḷādis, but these publications (henceforth denoted “suḷādi publications”) consisted of only the lyrics and no musical notation.[2] Musical notations of three suḷādis were printed in the 1904 publication, Saṅgīta Sampradāya Pradarśinī (SSP) by Subbarāma Dīkṣitar.[3] Other than these, some musical notations of suḷādi songs in Telugu script have been noticed by researchers in palm leaf manuscripts in the Thanjavur Maharaja Serfoji’s Saraswati Mahal Library (TMSSML) in the state of Tamil Nadu in South India.[4] Only three of these notations had been examined by researchers till a few years ago.[5] In the past few years, the present author has identified about forty suḷādi notations from the TMSSML manuscripts, and these have been the subject of her research.

[4] The TMSSM Library, built and maintained by the support of erstwhile rulers of Thanjavur such as the Maratha rulers (1676–1832) and the earlier Telugu Nayaka kings (1532–1675), has well over 40,000 manuscripts, including hundreds of palm leaf manuscripts with musical notations (Seetha 2001, 110). In the last few decades, digital and microfilm copies of the manuscripts have been made and preserved in TMSSML and the microfilm archive of the Indira Gandhi Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) in Bengaluru, Karnataka, South India. Several of the musical notations in palm leaf manuscripts have been transcribed in Devanāgari script and are also preserved in the TMSSML. The musical notations in these manuscripts follow the sargam system.[6]

[5] The sargam system of musical notation in Indian music has a long history. The earliest occurrence of melody being notated is seen in the Kuḍumiyāmalai inscription of the seventh or eighth century (Widdess 1979, 115–150). Later, in musical treatises of the medieval and modern period such as Mataṅga’s Bṛhaddēśī, Saṅgītaratnākara of Śārṅgadēva and many others, melodies were notated in sargam notation (Widdess 1995, 91). Rāgavibōdha of Sōmanātha (RV 5.14–166) seems to be the first treatise to symbolically represent embellishments to the musical notes with respect to performance on the vīṇā instrument.

[6] From the fifteenth century onwards, there have been a plethora of sargam song notations on palm-leaf manuscripts. These manuscripts have been preserved in various libraries in India, the TMSSM Library being one of them. In the course of study of a set of manuscripts from this library by the present author, it was seen that the notations appear to be mnemonic and do not contain detailed information about the embellishments to the musical notes and other finer nuances of the music. The exact pitch positions of the musical notes and their registers are difficult to determine, as there are no symbols to denote these. Damaged manuscripts and scribal errors also add to the complexity of the study and reconstruction of these notations. Studies on TMSSML musical notations pertaining to ālāpa, ṭhāya, gīta and prabandha songs have been carried out by Sastri (1958), Saraswathi (1991), Seetha (2001), Anandamurthy (2014) and Srilatha (2019).

[7] The discussion of the features of the song types ālāpa, ṭhāya, gīta and prabandha forms the core of the musical treatise Caturdaṇḍīprakāśikā (CDP) of the seventeenth century. Sathyanarayana describes caturdaṇḍī as “the community of ālāpa, ṭhāya, gīta and prabandha”. He further says “caturdaṇḍī is commonly understood as the four foundational pillars of music” (CDP 2002, 39). The presence of suḷādi notations among musical notations of ālāpa, ṭhāya, gīta and prabandha in the TMSSML manuscripts gives rise to the interesting possibility of sūḷādis having a connection with the caturdaṇḍī songs. However, there is no mention of suḷādi songs in the CDP.

[8] In a recent larger publication, (henceforth denoted “TMSSML Suḷādi notations publication”) the present author has attempted to analyse the features of the suḷādi musical form based on ten musical notations found in palm-leaf manuscripts in TMSSML (Rao 2022a). The methodology followed for that study involved identification and trans-notating suḷādi songs from TMSSML palm leaf manuscript notations and editing to fit into the metric cycles (where possible). The notations were then analysed to bring to light the structural, rāga and tāla features of the suḷādi. A comparison of the features of the musical form, rāga and tāla with descriptions in musical treatises was attempted in that study.

[9] The objective of this paper is to give a summary of the findings from the above publication, taking the example of a single suḷādi song. The key research questions that this paper tries to address are: i) What are the features of suḷādi that can be deciphered from the musical notations of Haridāsa suḷādi songs in the palm-leaf manuscripts preserved in the TMSSML in South India? ii) What are the features of the suḷādi tālas that can be observed in the aforementioned musical notations?

[10] It is necessary to go into the background of the suḷādis—their history and general features, before perusing the features of suḷādis in the TMSSML notations.

SUḶĀDI: AN OVERVIEW

[11] The Vijayanagara empire, which was founded in South India in the 14th century, laid the foundations of a cultural renaissance. One of the important cultural movements that flourished under this empire was the Haridāsa bhakti (devotional) movement in South India, which was nurtured by the Haridāsa followers of Ācārya Madhva. Haridāsaswere literally “servants of Hari (Viṣṇu)”. Their lives were dedicated to the service of Viṣṇu and they would constantly contemplate His name and divinity (M. V. K. Rao 1966, 27). Haridāsas belonged to two groups–“Vyāsakūṭa” and “Dāsakūṭa”. The former consisted of Vēdāntic scholars who studied Vēdas, Upaniṣads and other darśanas (philosophical schools). They spread to the masses the tenets of Dvaita Vēdānta in the Gīrvāṇa Bhāṣā (Sanskrit). The latter (Dāsakūṭa) comprised saint-musicians who spread the message of Dvaita Vēdānta through the Kannada language (M. V. K. Rao 1966, 34–35). Among the Vyāsakūṭa scholars were Śripādarāya, Vyāsatīrtha and Vādirāja. Among the Dāsakūṭasaints were Purandara Dāsa, Vijaya Dāsa, Gōpāla Dāsa and Jagannātha Dāsa. Suḷādi songs were composed by Śrīpādarāya, Vyāsatīrtha, Purandara Dāsa, Bēlūru Vaikuṇṭha Dāsa, Vijaya Dāsa, Jagannātha Dāsa, Gōpāla Dāsa and other Haridāsa saints, between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

[12] Śrīpādarāya was a scholar in the Mādhva (followers of Ācārya Madhva) sect born in 1404 ad. His prime disciple was Vyāsatīrtha who played a very important role as guru to the Vijayanagara kings. He was a great dialectician, famed for writing several seminal works in Sanskrit pertaining to Dvaita philosophy, foremost among them being Nyāyāmṛta (Jackson 2007, 219). Vādirāja Tīrtha was a disciple of Vyāsatīrtha, who was the author of many scholarly works in Sanskrit (Nagarathna 1980, 3–4). Purandara Dāsa was another well-known disciple of Vyāsatīrtha who was reputed to be a good musician and great composer, as mentioned in Saṅgīta Sampradāya Pradarśinī (SSP 2005, 4)

[13] The Haridāsas composed a huge body of different song types. Some of these were: 1) pada meant for congregational singing; 2) long poems, some of them being vṛttanāma, daṇḍaka, bhramara gīta; 3) ugābhōga—short, pithy, unsegmented compositions; 4) a koravañji dance drama depicting a gypsy fortune-teller; and 5) songs with varying metric cycles—suḷādi.[7] Śrīpādarāya has composed about eighty kṛtis, ugābhōgas and three suḷādis in Kannada. Vyāsatīrtha was also a composer of several padas, suḷādis and ugābhōgas in Kannada. In addition to padas, ugābhōgas, and suḷādis, Vādirājatīrtha composed the koravañji dance drama, which is bi-lingual and combines prose and poetry. Purandara Dāsa and later Haridāsas of the Dāsakūṭa sect also composed many padas, suḷādis, ugābhōgas and long poems.

[14] In the suḷādi publications, suḷādi themes are linked to the tenets of the philosophy of Ācārya Madhva. For example, the suḷādi “Tandeyāgi tāyāgi” by Vyāsarāya has been has been labelled pramēya and vyāpti (Gorabala 1958a, 19). Pramēya stands for the supremacy of Viṣṇu over all beings, his omnipresence and the dependency of all other creatures on Him (Gorabala 1952, III). Vyāpti literally means “scope” or “range” in Kannada. Here, it stands for the presence of Viṣṇu in the universe. Suḷādi lyrics convey esoteric philosophical teachings based on the Hindu scriptures, such as Vēdas, Upaniṣads and Purānas and the works of the monks of the Mādhva order. Suḷādi rendering is associated with a deep spiritual experience in the Haridāsa tradition. Suḷādis are linked to the various stages in manōnubhava (spiritual experience)—the development of vairāgya (detachment), bhakti (devotion) and jñāna (knowledge) (Gorabala 1954, 200).

[15] In Indian music, tāla is the temporal framework in which rhythmically organized compositions are set (Ramanathan, 1987). A set of tālas that are used in suḷādi songs is labelled suḷādi tāla. Every suḷādi song has several sections. Each section is set to a different suḷādi tāla. The term suḷādi tāla is seen for the first time in the musical treatise Caturdaṇḍīprakāśikā (CDP) of the 17th century (CDP 3.81–115). Veṅkaṭamakhin (VM), the author of CDP, describes a set of tālas labelled suḷādi tālas: jhōmpaṭa, dhruva, maṭhya, rūpaka, jhampā, tripuṭa, aṭha, and ēka. CDP notes that the seven tālas, dhruva, maṭhya, rūpaka, jhampā, tripuṭa, aṭha, and ēka, together occasionally with the tālas named jhōmpaṭa and ragaṇa maṭhya, should be used in gītas.[8] In the suḷādi publications, we find that the sections are set to dhruva, maṭhya, rūpaka, jhampā, tripuṭa, aṭa, and ēka, which provide the section names as well. (It may be noted that the tāla named “aṭa” in the publications is called “aṭha” in CDP.) However, there are instances where a suḷādi may not have all seven sections.Sometimes, the same tāla may be used for more than one section. An alternative name for maṭhya is maṭṭe, for tripuṭa is triviḍi and for aṭa is aṭṭa in some of the suḷādi publications. Though the sections are set to these tālas, the structure of tālas is not clearly decipherable in these publications as there are no markings to indicate the completion of cycles of tālas or the sub-division of the cycles.

[16] Suḷādi songs have a common pattern of thematic development. Hanumantha Rao Gorabala, a scholar and publisher of Haridāsa literature, mentions the various sections of suḷādis as linked to steps in the delineation of the theme as follows (Gorabala 1954, 202):

- dhruva – determination of the entity to which the suḷādi pertains

- maṭhya – delineation of the characteristics of the entity

- rūpakā – defining the causes of the entity’s characteristics

- jhampā – describing the characteristics of the entity resulting in thoughts in the mind in a cause–effect relationship

- tripuṭa – prayers for securing the result of the mental image formed by the characteristics of the entity

- aṭṭa – due to emotional surges in the mind, indulging in prayer, music and dancing

- ādi – due to the mind being in a state of bliss, more music and dancing at a faster pace.

[17] In the above description, the “entity” would pertain to a deity, or a theme, such as bhakti, pramēya etc. It is observed that in the suḷādi publications, jhōmpaṭa tāla and ragaṇa maṭhya are missing, and ādi tāla is present in some suḷādis. These tālas shall be taken up for discussion in a later section. As mentioned earlier, in suḷādi publications, all the tālas are not seen in all suḷādis, and the same tāla may repeat in two sections. In such cases, it is not clear how the delineation of the theme in the suḷādi would be structured.

[18] The basic temporal unit of a tāla in South Indian art music is called an “akṣara,” which corresponds to a “beat” in Western classical music. An “aṅga” is a grouping of akṣaras. A grouping of aṅgas in a particular sequence defines the structure of a tāla. For example, in present-day ādi tāla, the aṅgas“laghu” and “druta” occur in the following sequence: laghu, druta, druta. The total length of one cycle of the tāla is the sum of the lengths of its aṅgas. In ādi tāla, laghu has the length of 4 akṣaras and druta has 2 akṣaras. So, the length of one cycle of ādi tāla = 4+2+2 = 8 akṣaras. Tālas seen in present-day Indian music are cyclic in nature, that is, the pattern formed by the sequence of the aṅgasrepeats throughout the song. In the present paper, for this reason, tālas have been denoted as “metric cycles.” Each cycle of tāla is an “āvartana.”

[19] Suḷādi tālas have played a bigger role in South Indian art music than just being the tālas to which suḷādis are set. In the late medieval and early modern period, these have been employed in non-suḷādi songs as well, such as gīta and prabandha songs in the 16th to the 18th century.[9] Though suḷādi songs are not part of the repertoires of present-day South Indian art music, kṛti and varṇa compositions, by the 19th century composer Muddusvāmī Dīkṣitar and other later composers, set to suḷādi tālas, are part of the modern South Indian art music repertoires.[10] Suḷādi tālas also are used in beginner exercises called alaṃkāras, taught to students of South Indian art music in the present day. These alaṃkāras are modified versions of alaṃkāras listed in the chapter on svara in Caturdaṇḍīprakāśikā (CDP 3.81–115).[11]

[20] These tālas have also been indicated for different suḷādi sections in musical notations in SSP, as well as the TMSSML manuscript notations examined by the present author. In the three suḷādis for which notations are given in SSP, we find that the order of tālas mentioned above—dhruva, maṭhya, rūpaka, jhampā, triviḍa/tripuṭa, aṭa and ēka/ādi—is not adhered to. The same is true for suḷādis found in TMSSML manuscript notations: not all suḷādi tālas are present in all suḷādis, and the same tāla may be prescribed for more than one section. SSP notations and the TMSSML manuscript notations indicate that in suḷādis, the sections are sung in an order, without any section being repeated. However, within sections, some segments are repeated. There is also repetition of melody within a section for different sets of lyrics. The notations also give valuable information pertaining to the melodic features of the suḷādi songs.

[21] Since suḷādis have not been described in detail in most treatises of the medieval and modern period, it is somewhat difficult to examine the adherence of suḷādis to theoretical descriptions. Prabandhas were described in the thirteenth-century text Saṅgītaratnākara of Śārṅgadeva (SR) as musical compositions with a pre-defined structure (SR, 7.6). There were three classes of prabandhas—sūḍa, āli and viprakīrṇa (SR, 4.22). Sūḍas were further divided into the sub-classes śuddha sūḍa and sālagasūḍa. The latter were a set of seven songs (prabandhas) set to different tālas and sung in a particular order (SR, 4.311–314). Sathyanarayana and Sachidevi have opined that the suḷādi has evolved from the sālagasūḍa prabandhas described in the Saṅgītaratnākara and other sources.[12] Sālagasūḍa prabandhas are a set of seven prabandhas, sung in an order—dhruva, maṇṭha, pratimaṇṭha, niḥsāru, aṭṭatāla, rāsa,and ēkatālī. Each of the prabandhas has several varieties set to different tālas. Except for the dhruva prabandha, the other sālagasūḍa prabandhas, maṇṭha, pratimaṇṭha etc., are set to varieties of their namesake tālas. The sālagasūḍa prabandhas seem to have coalesced into a single song-type, the suḷādi, with each section of the suḷādi corresponding to a prabandha of the sālagasūḍa set (Sathyanārāyaṇa 1967, 11). An important distinction between the suḷādi and sālagasūḍa prabandhas is that in the former, there is a final section entitled jate or jati which usually spans two lines (pāda or “feet” in Kannada poetic parlance), which thematically summarizes the suḷādi. There is no sālagasūḍa prabandha corresponding to the jate.

[22] Sathyanarayana has based his analysis of suḷādi on several references in musical treatises. A brief mention of these would be pertinent for our discussion. The only clear description of suḷādi in a musical treatise is by Tulaja in SSA, comparing a suḷādi song with sālagasūḍa prabandhas. The song cited by him is “Hasugaḷa kareva dhvani,” a suḷādi in the rāga dēvagāndhārī composed by the well-known Haridāsa composer, Purandara Dāsa (SSA, 12.150–153). The notation of this suḷādi is given in SSP (SSP 1904 379–396)—this is probably copied from TMSSML manuscripts, which are currently unavailable. Tulaja asserts that this suḷādi exhibits the features of sālagasūḍa prabandhas. Apart from Tulaja, there are indirect references to suḷādi from other authors: Haripāladēva of the twelfth century, Paṇḍarīka Viṭṭhala of the sixteenth century (NN 3.305–306), and Catura Dāmōdara of the seventeenth century (SD 7.218-234).[13] These references pertain mainly to tālas with names similar to the suḷādi tālas of CDP, associating them with sālagasūḍa prabandhas. Viṭṭhala mentions an alternate “sūḍakrama” (order of the prabandhas) giving the names dhruva, maṇṭha, rūpaka, jhampā, triviḍa, aḍḍatāla, and ēkatālī, similar to the suḷādi tālas described by Venkaṭamakhī.Dāmōdara describes seven dances—dhruva, maṇṭha, rūpaka, jhampa, tṛtīya, aḍḍatāla, and ēkatālī—called Sapta Sālagasūḍakāḥ, associating them with prabandhasand tālas of the same names. Nāṭyacūḍāmaṇi, the work of Sōmanārya (sixteenth century) mentions that suḷādis are composed in several tālas and in different languages, but does not describe the songs (NC 2.187). In addition to three musical notations, SSP gives a description of suḷādi as a yathākṣara composition, set to the well-known sapta tālas of the alaṃkāras and ragaṇa maṭhya tāla, having the dhātus(sections) udgrāha, dhruva, and ābhōga, and being set to vilamba and madhya layas (slow and medium tempi; SSP 2005, 105). Suḷādi tālas appear to have evolved from the dēśī tālas prescribed for sālagasūḍa prabandhas. A detailed discussion about the evolution of the suḷādi tālas has been carried out by the present author elsewhere.[14]

[23] There is an extant oral tradition of suḷādi rendering in the present-day Karnataka state of South India, which is focussed more on the recitation of the lyrics rather than musical presentation. R. Sathyanarayana writes: “As to the actual mode of singing the suḷādis, it must be admitted that even their rare current usage today does not elucidate or illustrate, let alone emphasize, their rhythmic bias and specific characteristics. It is deeply regretted that there does not seem to be any continuous and consistent tradition of suḷādi singing even in the mādhva monastries of Karnataka where one would expect it to be kept alive, however crudely” (Sathyanarayana 1967, 42). This observation about the absence of a living musical tradition of suḷādis was corroborated by the present author’s field studies and interviews with scholars and practitioners of Haridāsa music.[15] Apart from personal interactions with Haridāsapractitioners, the author has come across some renderings of suḷādis on the internet. Most of the suḷādis are rendered with simple melodies, sometimes set in rāgas which clearly belong to the modern period.[16]

[24] Sathyanarayana has examined in detail the evolution of sālagasūḍas (CDP 2006, 398–418). He talks about the two different streams in which they evolved. In South India, suḷādis developed from them; however, suḷādis coexisted with sālagasūḍas till about the eighteenth century. The references of musical treatises in South Indian art music pertaining to sālagasūḍas have already been discussed. Sathyanarayana also refers to pan-Indian authorities such as Kṛṣṇadāsa, Haricandana, Haladhara Miśra, Ghanaśyāmadāsa, Gajapati Nārāyaṇadēva and describes the evolution of sālagasūḍas into only two major genres of dhruva and maṇṭha lakṣaṇa and proliferated into kṣudragītas, miśrasudas, saṅkīrṇasūḍas, and others.

[25] In the next section, the musical features of suḷādis, as found in the TMSSML manuscript notations by the present author are discussed. An attempt has been made to compare the musical features of suḷādis with descriptions in musical treatises.

SUḶĀDI FEATURES IN TMSSML MANUSCRIPT NOTATIONS

Identification and Transcription of Suḷādi Notations in the Manuscripts

[26] As mentioned earlier, several musical notations of suḷādis (sargam notations) have been noticed by the present author in the last few years, originally written in palm-leaf manuscripts kept in TMSSML. These notations are in Telugu script.

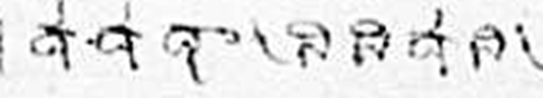

Figure 1. Part of the musical notation of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu“ in a TMSSML palm leaf manuscript in Telugu script captured on microfilm, Roll no. 415, Record No. 4852—folios 020 to 022, from the archive of IGNCA, RCB.

[27] The suḷādi notations found so far in TMSSML are about forty in number. In these manuscripts, the number of suḷādi notations is very small as compared to those of gītas, prabandhas, ālāpas, and ṭhāyas, which run into hundreds. Several indexes of the gīta, prabandha, ālāpa, ṭhāya, and suḷādi songs found in the TMSSML manuscripts have been prepared by the present author.[17] More indexes are under preparation as part of her ongoing research.

[28] The suḷādi notations that were decipherable, complete and appeared to have few scribal errors were taken up for study. About twenty musical notations of suḷādis have been examined so far by the present author. These notations were studied from paper manuscripts (paper copies of palm leaf manuscripts) obtained from TMSSML and microfilm copies of the palm leaf manuscripts from IGNCA, Bengaluru.

Figure 2: Part of the musical notation of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu” in the TMSSML paper manuscript in Dēvanāgarī script, B11575, page numbers 33 to 39. Image courtesy TMSSML, Thanjavur.

[29] Identification of the manuscripts that contained suḷādi notations, transcription and editing of the suḷādi songs posed several problems. These included:

-

A perusal of the manuscript catalogues/microfilm catalogues did not yield the information about presence of suḷādi notations in manuscripts. Many suḷādi notations were found in manuscripts entitled gītādi, gītālu, and nānāvidha gītam (miscellaneous songs).

-

As mentioned earlier, suḷādi songs were very few in number as compared to other songs in the TMSSML manuscripts. Due to scribal errors, unclear scripts or the manuscripts being damaged, song notations were not clearly identifiable in some instances.

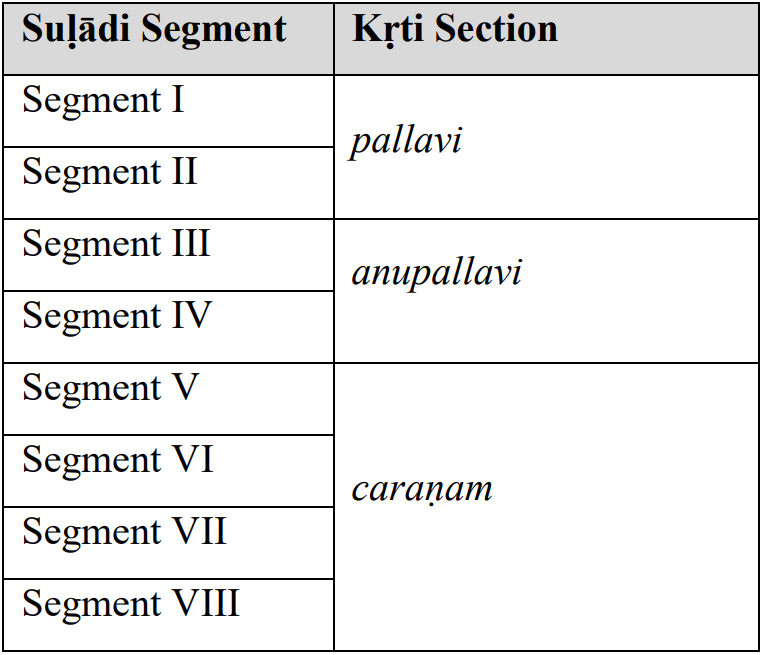

-

Scribal errors, damaged manuscripts or incomplete notations posed challenges in reading suḷādi notations (Figure 3).

-

The octave registers and the varieties of svaras (kōmala/tīvra, i.e., flat/sharp) were not indicated in any of the notations. This posed challenges in determining the exact varieties of the svaras used as well as the octaves in which the melodies traversed. The other problem with the notation pertained to the tāla cycles. In the present-day Indian musical sargam notation, vertical lines are used to demarcate tāla cycles and aṅgas. In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, there were vertical lines between the svara passages. However, the placement of the vertical lines did not clearly indicate the tāla structures in all the cases.

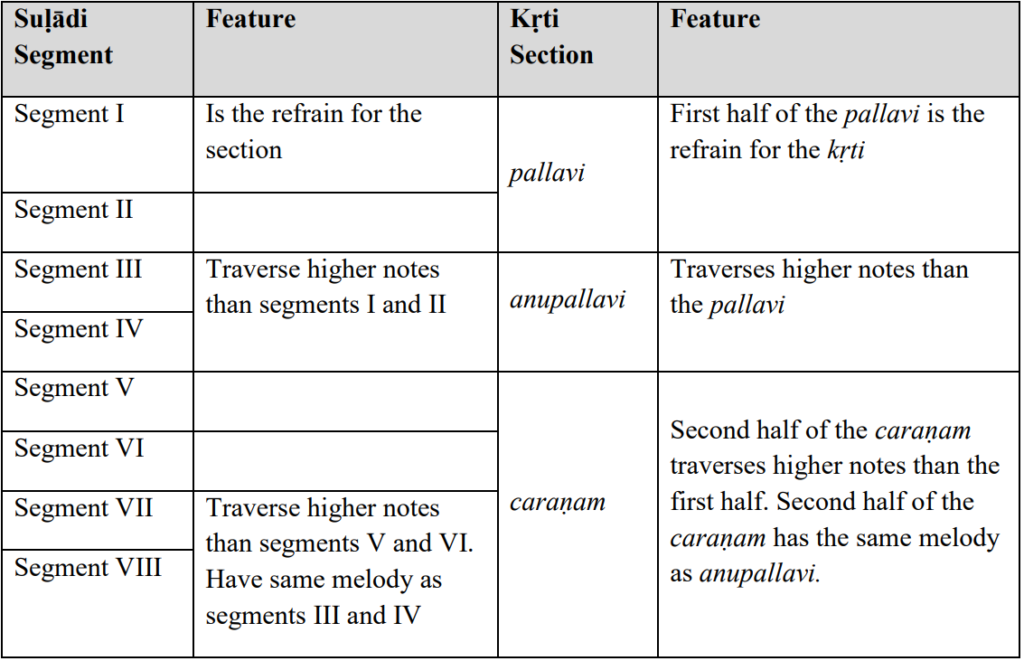

Figure 3. Damaged portion of a TMSSML manuscript captured in microfilm.

Image courtesy: IGNCA, RCB.

METHODOLOGY FOR TRANSCRIBING AND EDITING NOTATION

Transcribing Suḷādi Notations

[30] The sụlādi notations were firsttranscribed in Roman script.

Editing and Reconstruction of the Songs

[31] The varieties of the svaras in the notations were determined by referring to the theoretical descriptions of the rāgas of the suḷādis given in musical treatises belonging to the post-15th century period—Svaramēlakalānidhi of Rāmāmātya (SMK), Sadrāgacandrōdaya of Puṇḍarīka Viṭṭhala (SRC), Rāgavibōdha of Sōmanātha (RV), Saṅgītasudhā of Gōvinda Dīkṣita (SSudha), Caturdaṇḍīprakāśikā of Veṅkaṭamakhi (CDP), Rāgalakṣaṇamu of Śāhaji (RL-S) and Saṅgītasārāmṛta of Tulaja (SSA). In addition to describing the varieties of the svaras present in the rāgas, as mentioned earlier, RL-S and SSA give svara passages of different types of songs (including suḷādis) as examples while describing the features of rāgas. Some of the suḷādi svara passages cited in these two texts were found in the TMSSML manuscript notations by the present author. For these suḷādis, the presence of the svara passages in the two texts facilitated the determination of the svara varieties with greater certainty (see below §117–127).

[32] Though it was not possible to determine the octave registers of the svara passages, in several suḷādi sections, the flow of the melody indicated movement across different octaves. The audio samples attached to this paper (which are the performed samples of some suḷādi sections) have melodic movements from the middle to higher or lower octaves—these are only conjectural and not definitive.

Reconstructing the Suḷādi Sections, Their Rhythm and Metre

[33] For the suḷādi sections where the lyrics were available in the suḷādi publications, the printed lyrics were compared with those of the manuscript notations. The suḷādi sections in the notations were then demarcated into segments (i.e., phrases) based on the lyrics. If published lyrics were not available, then an attempt was made to divide the section into segments based on the melodic construction. (It shall be discussed subsequently that many suḷādi sections in the notations had melody repetition within the section; this enabled the division of the section into segments).

[34] In many instances, each segment could be further divided into sub-segments based on the lyrical and melodic construction. In these cases, it was found that each such sub-segment had also been demarcated by vertical lines in the TMSSML manuscript suḷādi notation. In order to determine the akṣara count for each sub-segment, the following method (which is a convention in present-day South Indian art music) was employed: A svara with a short syllable, that is, sa, ri, ga, ma, pa, dha or ni is treated as one akṣara. A svara with a vowel elongation such as sā, rī, gā, mā, pā, dhā, nī is treated as two akṣaras. If the akṣara count thus derived for a sub-segment matched the akṣara count for the tāla in CDP for all the sub-segments in the section, the tāla structure for the section could be determined. There were some instances where most of the sub-segments of a section had the akṣara count which matched the akṣara count of the tāla specified in the CDP, with the exception of a few sub-segments. The reasons for exceptions appeared to be two: a) scribal errors, b) svaras and corresponding lyrical syllables having vowel elongations that possibly spanned more then two akṣaras but were not indicated as such in the notation.[18] In such cases of non-conformance, the sub-segment was edited by elongating svaras with vowel extensions (along with corresponding lyrical syllables) to conform to the CDP akṣara count.

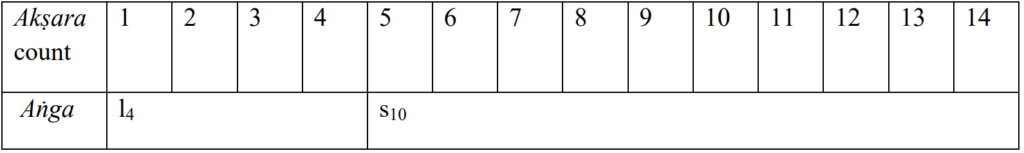

[35] In some suḷādi sections where the vertical lines indicated the tāla structures, there were additional vertical lines within the sub-segments that appeared to indicate the further distribution of the tāla cycle into aṅgas. This was seen in the case of the tālas dhruva, maṭhya, ragaṇa maṭhya, and aṭa. For example, a suḷādi section set to the tāla maṭhya had sub-segments where the svara passages demarcated by vertical lines had the akṣara counts of 4, 2, 4 indicating the akṣara counts of the aṅgas of the tāla, with total akṣara count of the tāla cycle (sub-segment) being 4+2+4 = 10. In the case of rūpaka, tripuṭa, jhampe, and ēka tālas, there were no vertical lines within the sub-segments. For these tālas, the akṣara counts only for the total tāla cycle (sub-segment) could be determined and the distribution of the tāla into aṅgas could not be arrived at.

[36] In Indian music, the term laya (which represents the time duration between two hand-actions used to reckon the tāla) is used as an indicator of the speed at which the music has to be rendered. Laya is of three kinds: vilamba (slow), madhya (medium), and druta (fast). However, in South Indian art music, laya is never defined in absolute terms. It has been seen that artistes can render the same composition in relatively different speeds even though the composition may be set to a particular laya—vilamba laya or madhya laya. It must be mentioned that the speed of rendering the suḷādi sections was not determinable from the TMSSML suḷādi notations—no laya was specified in the notations. While transcribing the suḷādi notations into staff notation, one akṣara has been taken as the equivalent of a quarter-note (crotchet).

[37] An example of editing a suḷādi section where there are a few sub-sections having akṣara counts different from that specified in CDP is seen below.

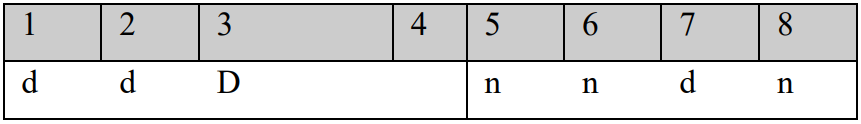

[38] In the tables below, the first column indicates the section number. The numbers 1, 2 etc., indicate the akṣaras of the tāla. The svaras sa, ri, ga, ma, pa, dha,and ni have been denoted with the letters s, r, g, m, p, d, n. Uppercase letters indicate svaras with vowel extensions and lowercase letters indicate svaras without vowel extensions. For example, the letter D indicates dhā whereas the letter d indicates dha.

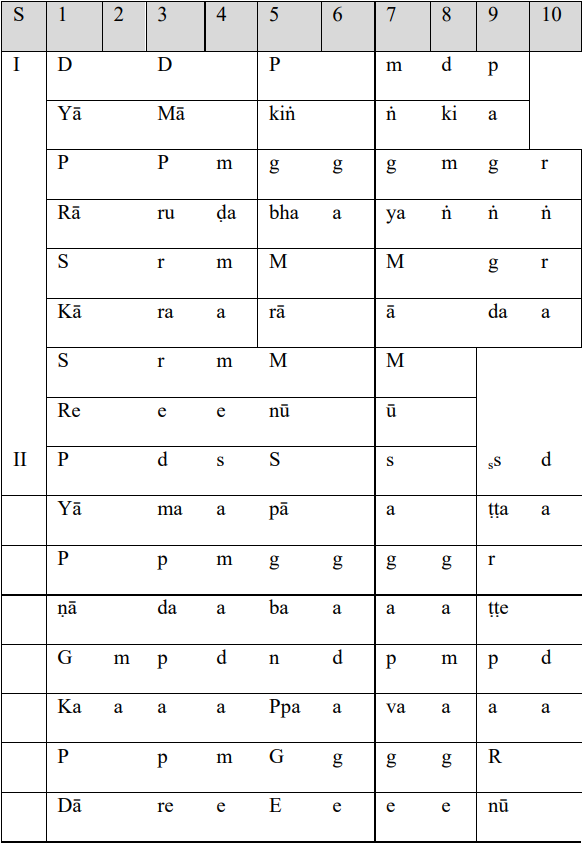

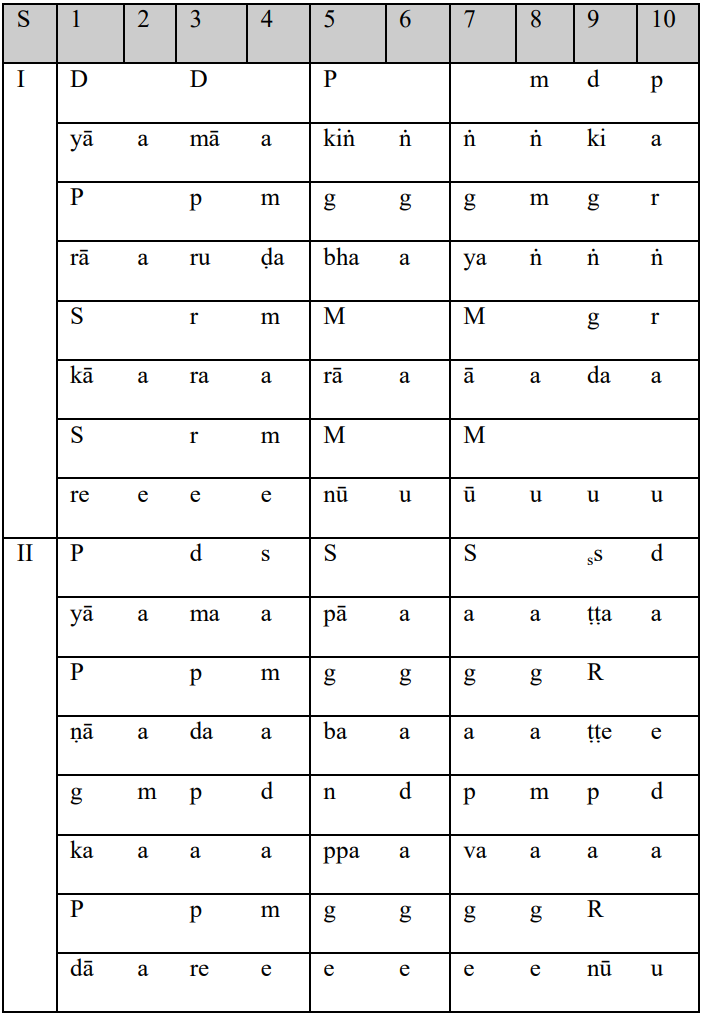

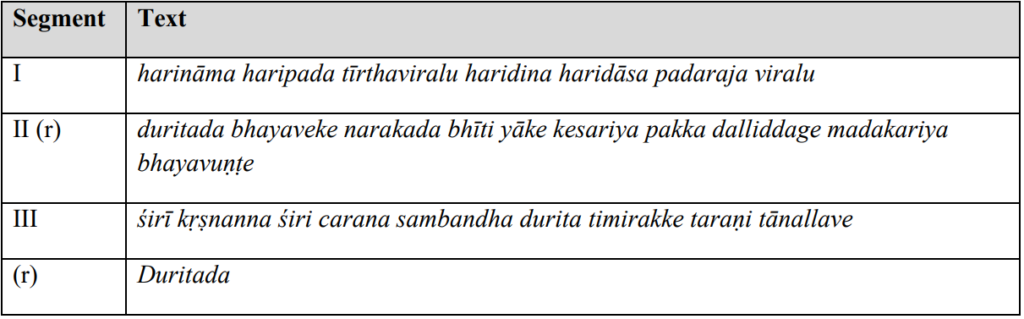

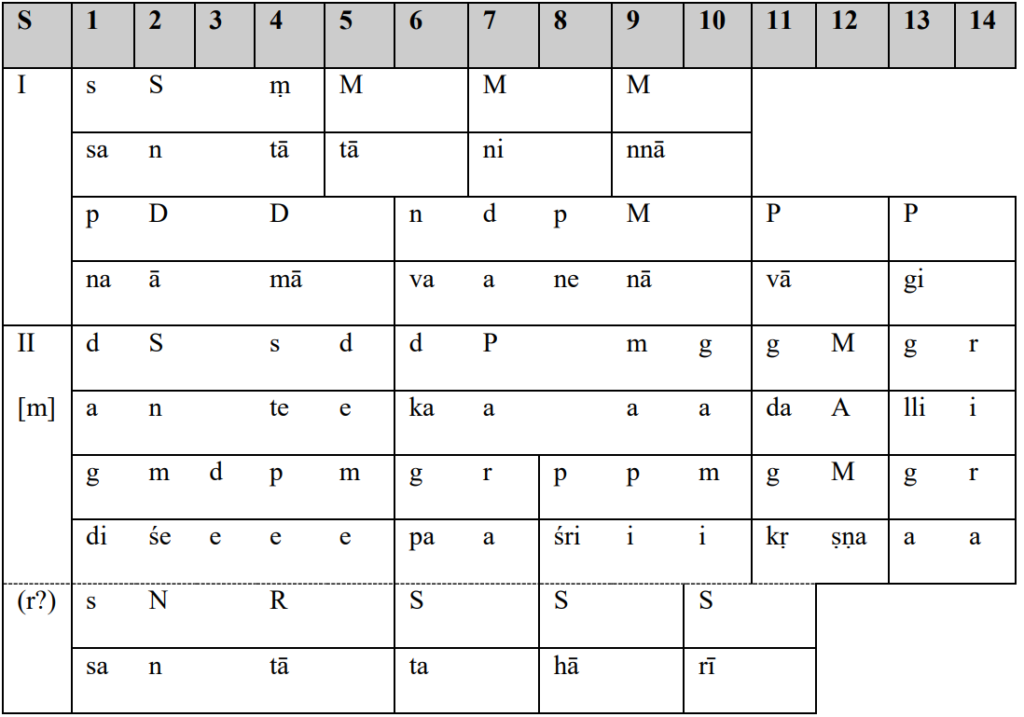

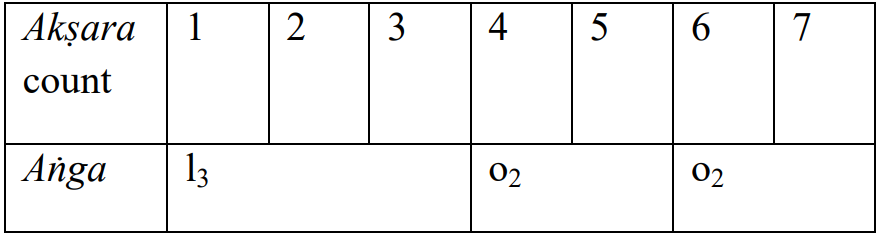

[39] The transcription of the original notation of the first two segments of a suḷādi section set to the tāla maṭhya is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Transcription of the original notation of a suḷādi section in tāla maṭhya.

[40] In Table 1, we see that most of the sub-segments span 10 akṣaras, though there are some sub-segments which do not. For those sub-segments that span less than 10 akṣaras, the akṣara count was increased by elongating some vowels of the svaras and the corresponding lyrical syllables to fit into the tāla cycle structure of 10 akṣaras as illustrated in Table 2.

Reconstructing the Refrain in a Suḷādi Section

[41] A suḷādi section may have the first few syllables or words of a segment, or the entire segment repeated after other subsequent segments, some times more than once within the section. These repeating elements constitute the refrain for the section. The refrain may occur more than once in the section.

Table 2. Transcription of the edited notation of a suḷādi section in tāla maṭhya.

[42] In the first section of a suḷādi, the first few words or syllables of the first segment or the entire first segment could be the refrain. In subsequent sections, the first few words or syllables of a middle segment or an entire middle segment could be the refrain.

[43] In the TMSSML notations, in some cases, refrain is indicated by the word antari. In other cases, refrain is indicated by repeating words of a segment. This is done as follows:

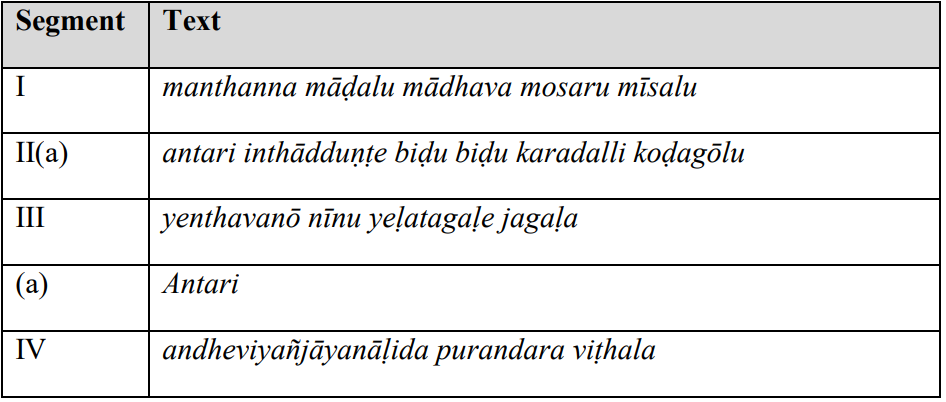

[44] When the label antari precedes a segment, the refrain is the first few words or syllables of that segment, or the entire segment itself. In such instances, the word antari again occursafter a subsequent segment. The second antari is an instruction to repeat the refrain which follows the first antari. [45] An example of a section of a suḷādi is given in Table 3. The antari is indicated by a in the table. In Table 3, we see that that the segment II is preceded by the label antari. It indicates that the word(s) starting with inthādduṇṭe constitute the refrain. After segment III, we have the word antari, which is an instruction to sing the refrain inthādduṇṭe….

Table 3. Lyrics of a suḷādi section having antari.

Table 4. Lyrics of a suḷādi section where refrain is indicated by the starting words or syllables of a segment.

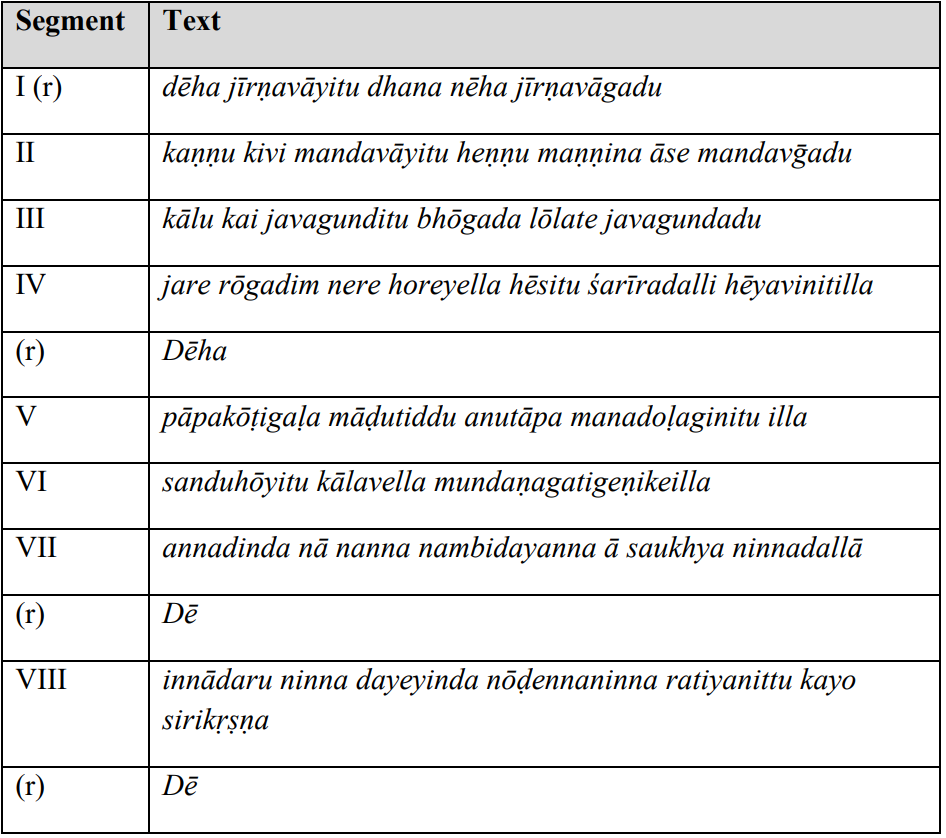

[46] Either the starting syllables or words of a segment, or the entire segment, are repeated after a subsequent segment. An example of this type of refrain in a suḷādi section is given in Table 4. The refrain is indicated by (r) in the table. We see that the refrain is indicated by the word deha after segment IV and de after segment VII and VIII. The word dēha is the starting word of segment I. The occurrence of the word dēha after segment IV and the syllable dē after segments VII and VIII indicates that the refrain dēha is to be sung after the segments IV, VII and VIII.

[47] The findings of the TMSSML Suḷādi notations publication have been summarized in the subsequent sections. The notation of one suḷādi has been taken as an example in order to illustrate the musical features of the suḷādis.

INSIGHTS INTO SUḶĀDI FEATURES FROM TMSSML MANUSCRIPTS

[48] An example of a suḷādi reconstructed from TMSSML manuscripts is presented in this section. This suḷādi exhibits many of the features of musical form, rāga and tāla mentioned in the earlier sections. This suḷādi—“Dēha jīrṇavāyitu”—has the nom de plume “siri kṛṣṇa”, and is one of the songs in the publication Śrī Vyāsarāyara Kṛtigaḷu, that is, compositions of Vyāsarāya (Nagarathna, 2001). Hence, this suḷādi appears to be a composition of Vyāsatīrtha/Vyāsarāya (1447 ad–1539 ad), who was guru to Vijayanagara emperors, Dvaita Vēdānta scholar and the preceptor of Purandara Dāsa (Sathyanarayana, 1967, 7). This suḷādi is set to the rāga ārdradēśī. The microfilm copy of the notation of this suḷādi (Roll no. 415, Record No. 4852—folios 020 to 022) in the microfilm archive of IGNCA-Regional Centre, Bengaluru has been examined for this study. In case of unclear script, scribal error or missing svara/sāhitya (lyrics) passages, another paper manuscript B11575 page nos. 33 to 39 (having the notation of the same suḷādi) from TMSSM Library, Thanjavur was consulted to supplement the missing information. The suḷādi has six sections. The tālas specified for the first five sections in the TMSSML manuscript notation are: aṭa, ragaṇa maṭhya, maṭhya, aṭa, and ēka. For the last section (which is labeled jati), no tāla was given in the manuscript notation. However, upon transcription and editing, the aṭa tāla was assigned to the suḷādi section. The methodology for editing the suḷādi sections shall be discussed subsequently. The lyrics of the suḷādi as found in the TMSSML notation were found to be unclear or meaningless in some places. In such instances, appropriate lyrics were substituted from those published in Śrī Vyāsarāyara Kṛtigaḷu.

[49] Following is a description of three of the reconstructed sections of the suḷādi (Sections 1, 2 and 6) from the TMSSML notations, and the features observed therein. For each section, first, the text of the section is given. After that, the unedited original sargam notation of the section has been given in Roman script, followed by the edited sargam notation. Then the staff notation corresponding to the edited sargam notation has been given, lastly followed by audio clips of the rendering of the section.

Table 5. Transcription of a melodic passage from a suḷādi notation with vertical grid lines.

Figure 4. Image of a melodic passage from a TMSSML manuscript suḷādi notation.

[50] Some conventions have been followed for the sargam notation:

Vertical grid lines indicate the presence of a single vertical line “|” in the microfilm notation, for example as shown in Table 5. Table 5 gives the transliteration of the melodic passage from the notation of a suḷādi from a TMSSML manuscript, shown in Figure 4.

Akṣaras have been indicated by the numbers 1, 2, 3… etc. in the top (heading) row.

The heading “S” of the first column indicates “segment.”

Segments have been labelled as I, II, III, IV etc.

The refrain is marked (r) if it is clearly indicated in the notation in by the occurrence of initial syllables/words/phrases of a segment (with or without svaras) after another segment

If a segment is labeled mudra in the manuscript notation, it is indicated by (m) in the notation tables. If a segment is not labeled mudra in the manuscript, but the mudra (nom de plume) of the composer is seen in the lyrics, it is indicated by [m] in the notation tables.[19]

[51] The edited lyrics, notation and transcription of Sections 1, 2 and 6 of the suḷādi are given in Tables 6–14 and Examples 1–3. Sections are numbered 1, 2, 3 etc, and are named aṭa [tāla] etc., as in the TMSSML notation. Within each section, segments are numbered I, II, III etc.

Section 1: aṭa (tāla)

[52] The following structural features are seen in this section:

Segments I and II have identical melodies; segment III employs higher svaras than the first two segments.

No melodic notation is given for the segments V–VIII, but the instruction in Telugu munupaṭi svarame implies that the melodies of segments I–IV should be repeated in the segments V–VIII.

In the original notation, the first word of segment I, “dēha”, occurs along with a svara passage after segment IV, and the starting syllable of segment I “de” occurs after segments VII and VIII. This indicates that the word “dēha” is to be sung after the segments IV, VII and VIII as a refrain. It is not clear if the remaining part of the first segment after “dēha” is also to be sung as part of the refrain or the refrain constitutes only “dēha.” When the word “dēha” occurs as the refrain, the svaras seem to be slightly different from the starting svaras of the first segment.

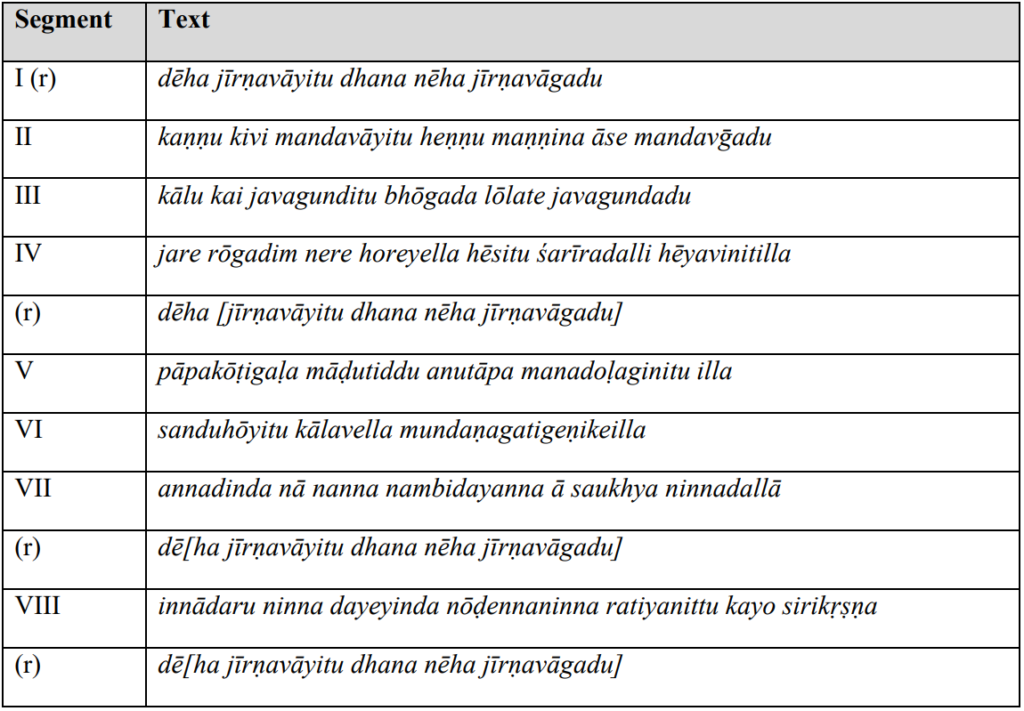

Table 6. Lyrics of the first section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

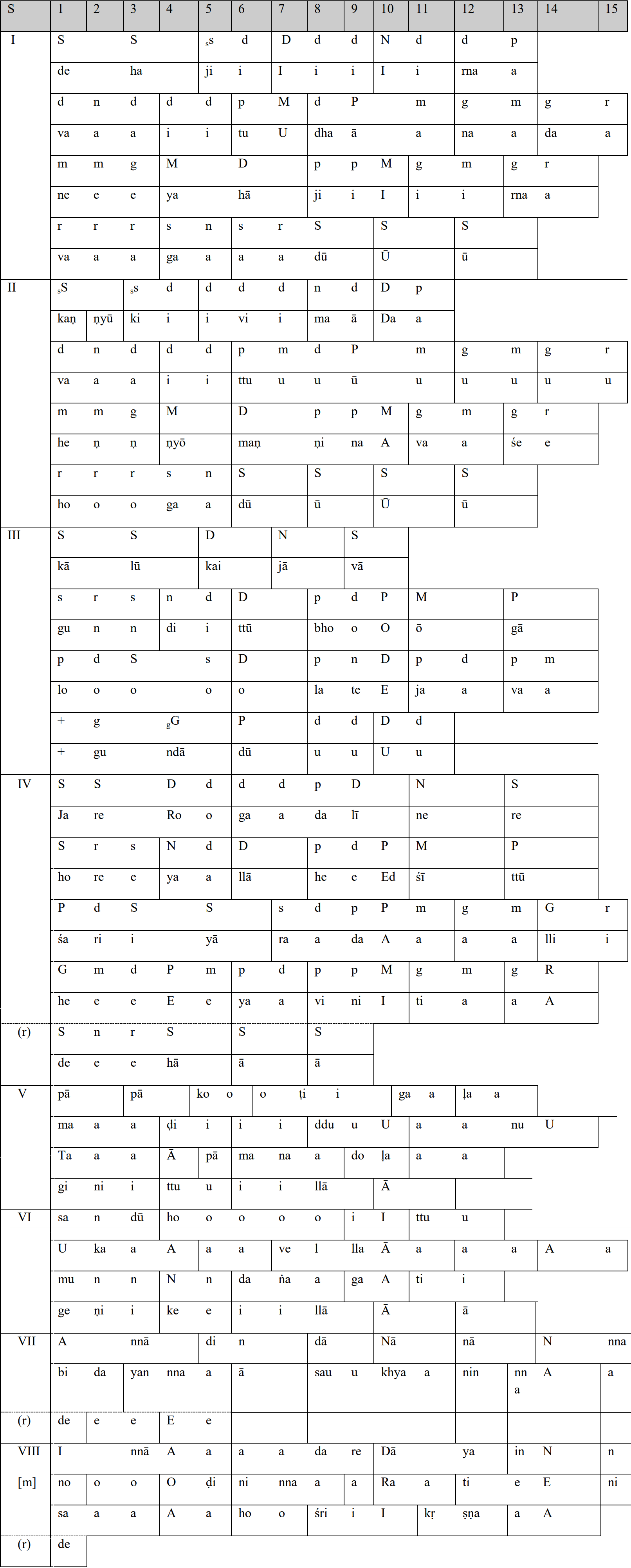

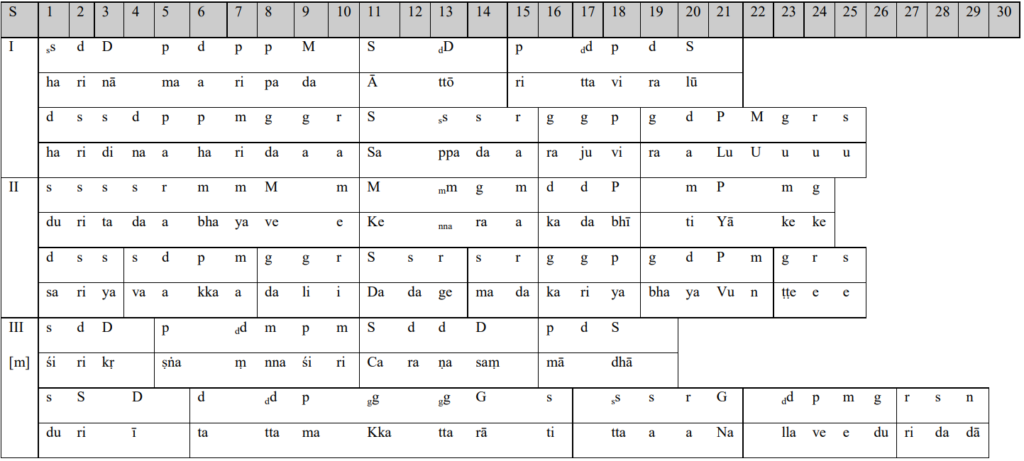

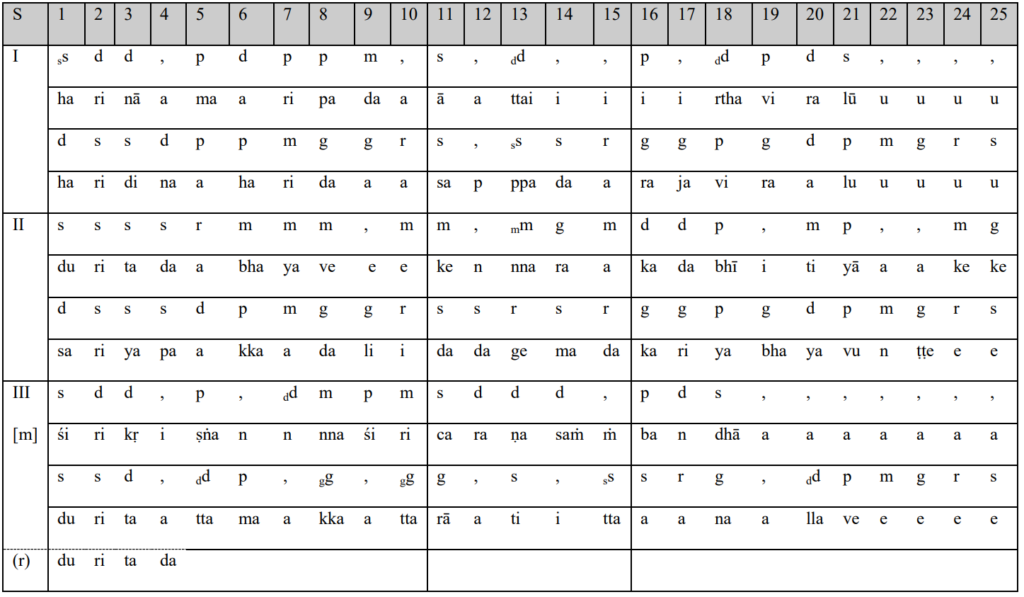

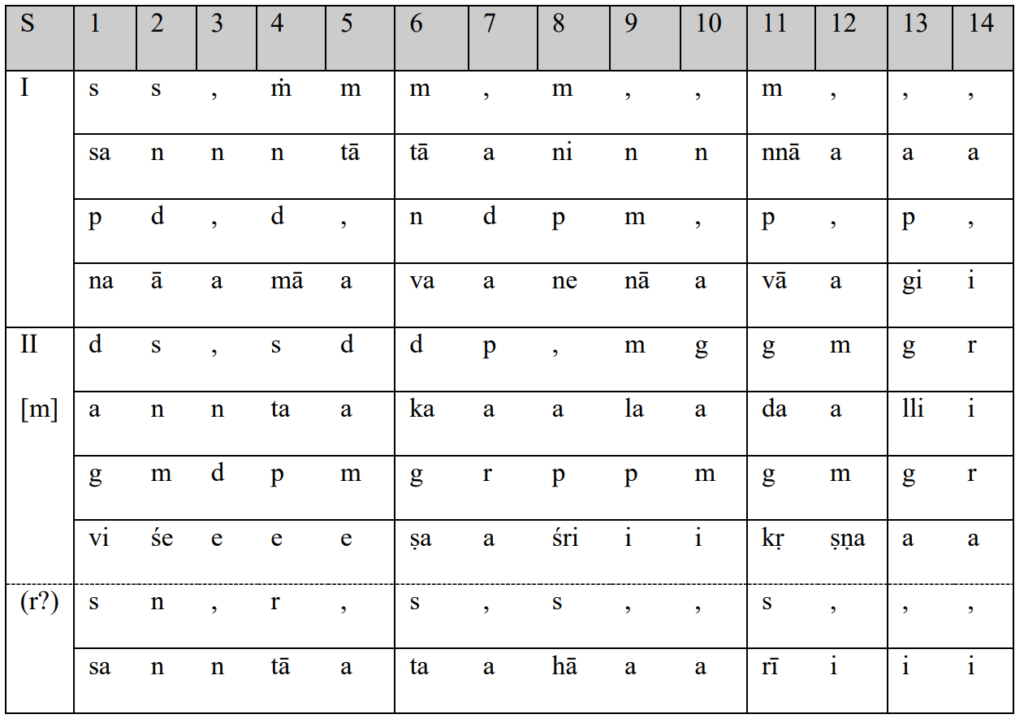

[53] Given in Table 7 is the Roman transcription of the original notation of Section 1 in the TMSSML manuscript:

Table 7. Transcription of the original TMSSML manuscript notation of the first section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu”

[54] Given in Table 8 is the Roman transcription of the edited sargam notation of this section. In this transcription, the svaras with vowel extensions have been denoted by lowercase letters followed by commas, instead of uppercase letters (as in Table 2). For example, the first svara “sā” is denoted by “s , ,” instead of “S.” This has been done to indicate the exact number of akṣaras spanned by the svaras with vowel extensions.

Table 8. Transcription of the edited notation of the first section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

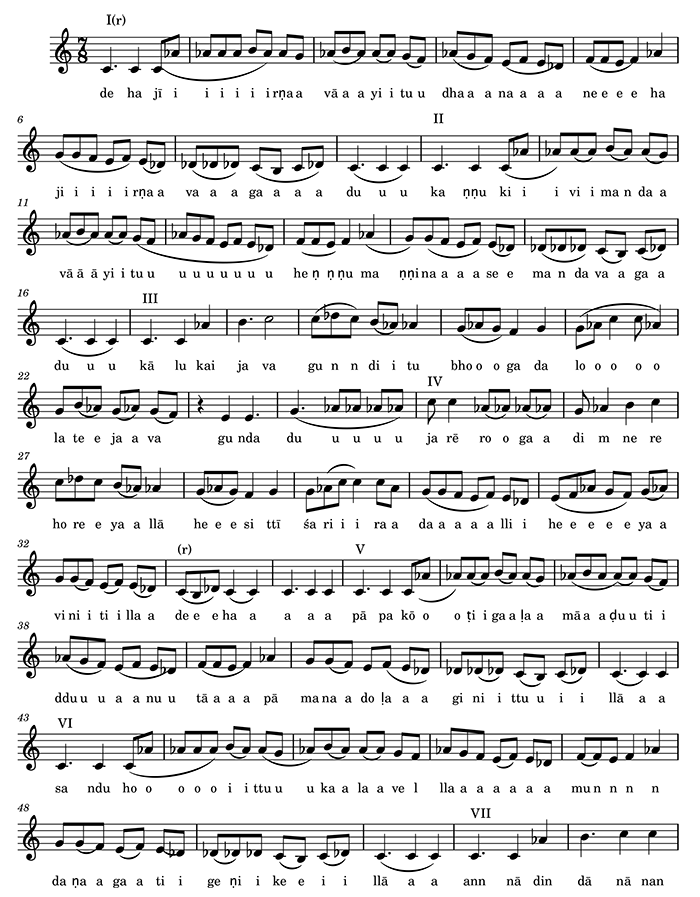

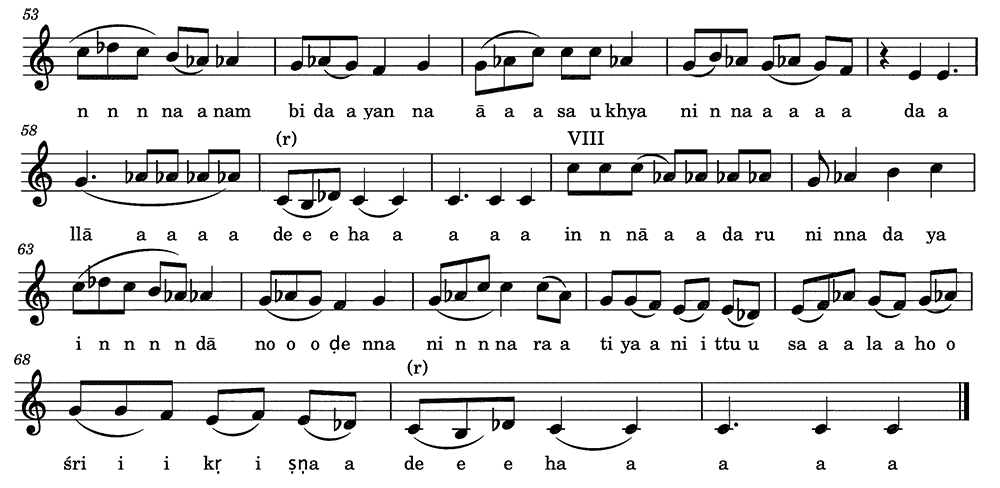

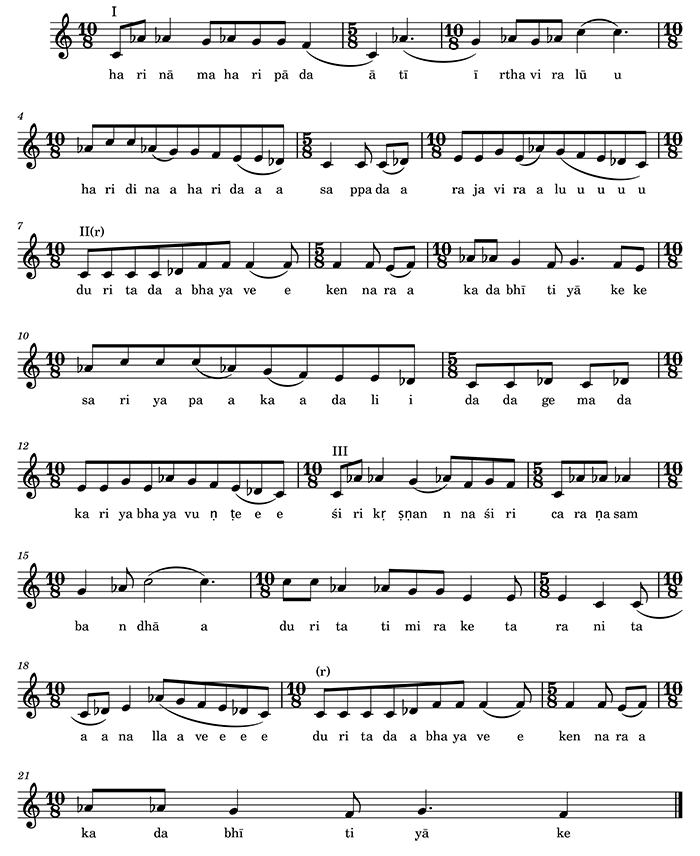

[55] Example 1 is the transcription in staff notation of the edited notation of Section 1.

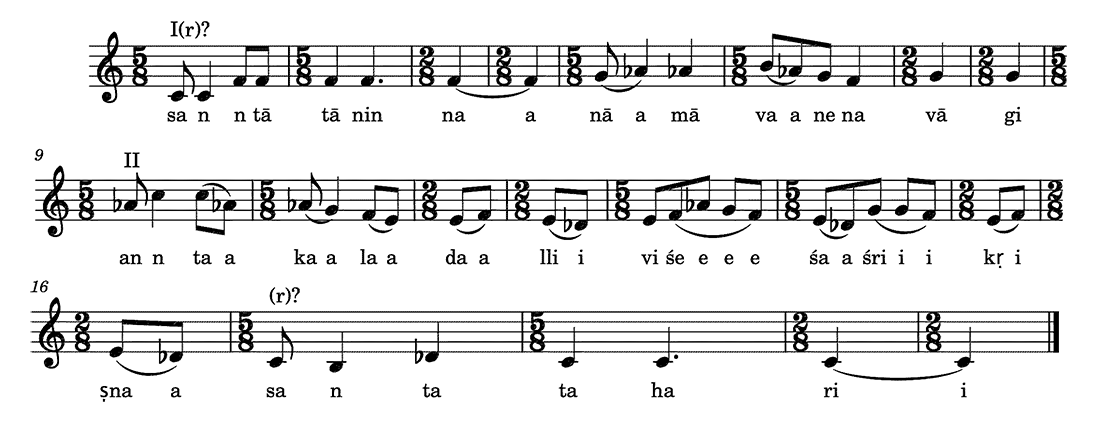

Example 1. Suḷādi “Dehajīrṇa,” Section 1. Rāga: ārdradēśī. Tāla: aṭa. Segments are numbered I– VIII. Barlines denote aṅga segmentation implied in the original notation (see below, §105). Audio clip 1: Section 1. Sung by the author. Pitch: sā = G. Claps denote aṅga segmentation of aṭa tāla as 3+4.

Section 2: ragaṇa maṭhya (tāla)

[56] The following structural features are noted in this section:

Segments I and III seem to have very similar melodies.

The word duritada occurs at the end of segment III. It is not clear if only duritada is to be sung or the entire segment II starting with duritada is to be sung as the refrain. To complete the tāla āvarta cycle, the words from duritada up to yāke need to be sung. (Please refer to the edited sargam notation of section 2 which follows, see below, Table 10).

Table 9. Lyrics of the second section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

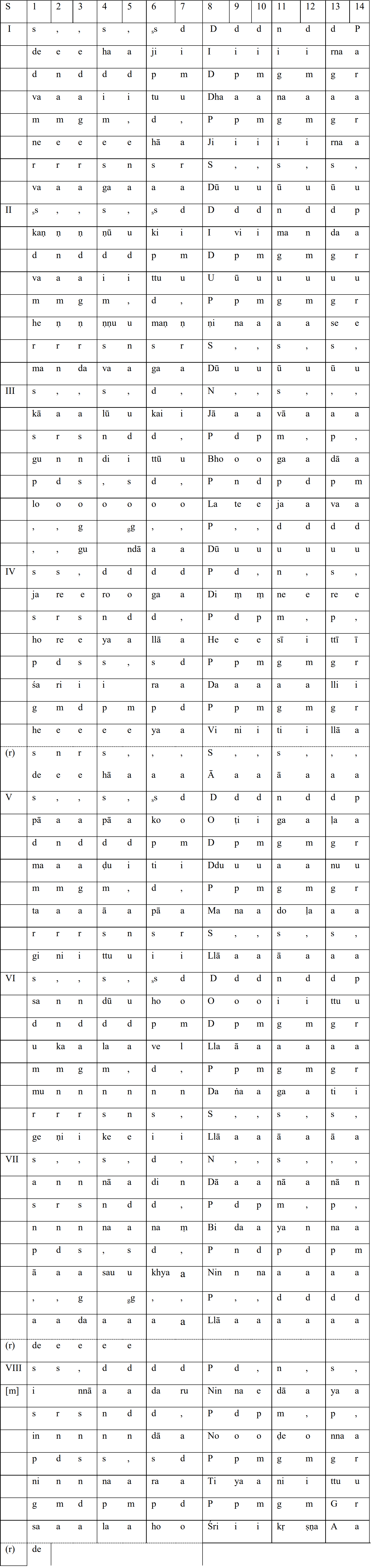

[57] Table 10 shows the Roman transcription of the original notation of Section 2 in the TMSSML manuscript.

Table 10. Transcription of the original TMSSML manuscript notation of the second section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

[58] Given in Table 11 is the Roman transcription of the edited sargam notation of Section 2 in the TMSSML manuscript.

Table 11. Transcription of the edited notation of the second section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

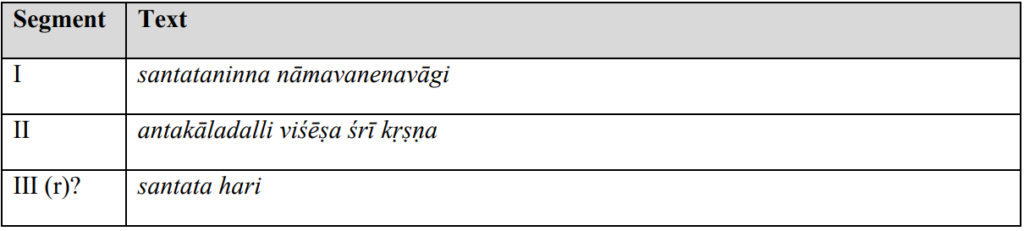

[59] Example 2 is the transcription in staff notation of the edited notation of Section 2.

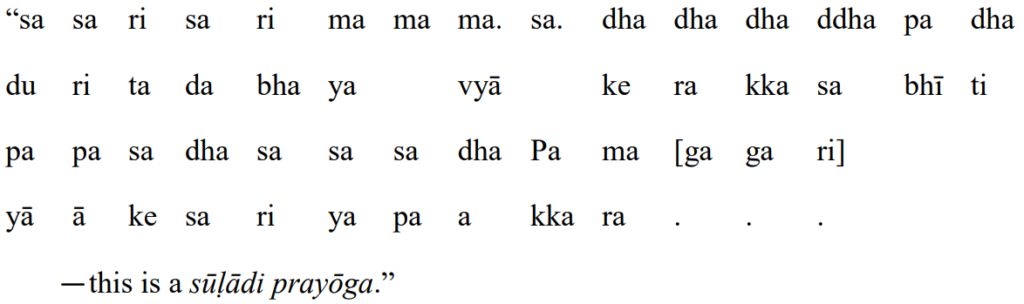

Example 2. Suḷādi “Dehajīrṇa”, Section 2, Segments I to III. Tāla: ragaṇa mathya. Segments are numbered I–III. Barlines denote aṅga segmentation implied in the original notation (see below, §93). Audio clip 2: Section 2. Sung by the author. Pitch: sā = G. Claps denote the aṅga segmentation of the tāla ragaṇa maṭhya.

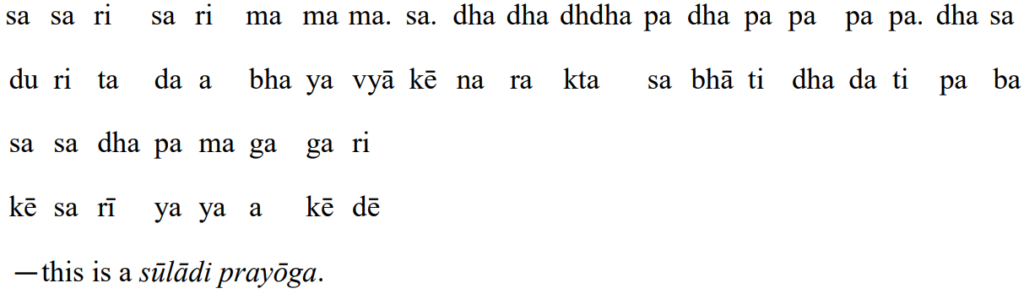

Section 6: jati (aṭa tāla)

[60] The following structural features are noted in this section:

There appears to be no repetition of melody in the above segments.

The starting word of segment I “santata” occurs after segment II as a refrain. However, the the svaras of the refrain seem to be different from the starting svaras of segment I. There is also another word “hari” in the refrain, which is not there in segment I.

Table 12. Lyrics of the sixth section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

[61] Given in Table 13 is the Roman transcription of the original notation of Section 6 in the TMSSML manuscript:

Table 13. Transcription of the original TMSSML manuscript notation of the sixth section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

[62] Given in Table 14 is the Roman transcription of the edited sargam notation of the jati section in the TMSSML manuscript.

Table 14: Transcription of the edited notation of section 6 of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu.”

[63] Example 3 is the transcription of the edited notation of this section in staff notation.

Example 3. Suḷādi “Dehajīrṇa”, Section 6, segments I to II. Tāla : jate (aṭa). Segments are numbered I–II. Barlines denote aṅga segmentation implied in the original notation (see below, §105). Audio Clip 3: Section 6. Sung by the Author. Pitch: Sā = G. Claps denote aṅga segmentation of aṭa tāla.

SUMMARY OF FEATURES OF SUḶĀDIS OBSERVED FROM TMSSML MANUSCRIPTS

The Suḷādi Musical Form

[64] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations publication (Rao 2022a, 251–267), the structural features of the suḷādisas seen in the TMSSML notations have been compared by the present author with sālagasūḍa prabandha features given in musical treatises. A summary of the findings is presented below. Many of these features are illustrated in the suḷādi notation given in the previous section.

[65] All the sections of the suḷādi have the nom de plume of the composer. The first sections and other sections of suḷādis exhibit certain typical features, irrespective of the tālas they are set to. First sections are usually longer than other sections. In the first sections, when a refrain is indicated, it is part, or all, of the first segment. In other sections when the refrain is indicated, it is part of or all of a non-first segment and usually labelled “antari.” It was seen that the first and other sections of the suḷādis exhibit some of the features of the first sālagasūḍa prabandha, dhruva, and other sālagasūḍa prabandhas respectively. These are as follows.

First Sections

[66] In the Saṅgītaratnākara, the dhruva prabandha (the first of the sālagasūḍa prabandhas) is described as follows (Rao 2022a, 252): It has six segments. The first two segments have an identical melody; the third segment has a melody traversing higher notes. These three segments together constitute the udgrāha section which is sung twice. The next three segments, which are together termed ābhōga section, have a similar structure—the first two with identical melodies and the next segment getting into higher pitch positions. The last segment carries the name of the patron, deity or composer, called mudrā. The song comes to rest on the first segment of the udgrāha.

[67] In some first sections of suḷādis, features similar to the features of the dhruva prabandha are noted. For instance, in the first section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu,” the first half of the section could be considered the udgrāha, and the second half, ābhōga. The first half of the section comprises four segments and the second half, another four. The first two segments have identical melodies and the next two traverse higher notes. The fifth and sixth segments again have identical melodies and the seventh and eighth traverse higher notes. The refrain is indicated by “dēha,” which is the starting word of the first segment.

Other Sections

[68] In the Sangītaratnākara, the maṇṭha prabandha is described as follows (Rao 2022a, 253): It has an udgrāha dhātu (melody) having one or two yatis or pauses, dhruva dhātu occurring twice, an optional antara dhātu and an ābhōga dhātu. If antara is present, after singing it, dhruva is sung, and then ābhōga, and the song ends on dhruva. The text does not explicitly give the structure of other non-dhruva prabandhas—pratimaṇṭha, nihsāru, aḍḍatāla, rāsaka, and ēkatālī—in terms of udgrāha, ābhōga etc., but says that they are similar to maṇṭha. In this text, descriptions of varieties of rāsaka mention ālāpa in the beginning, middle or end of dhruva dhātu or at the beginning of udgrāha. In the description of the varieties of ēkatālī, the text mentions only udgrāha and antara, but not dhruva.

[69] In some non-first sections of suḷādis, features similar to sālagasūḍa prabandhas other than dhruva are noted. For instance, in the second section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu,” there are three segments. The first could be considered the udgrāha, the second the dhruva and the third the ābhōga. We find that the second segment is the refrain, as it is sung after the third segment and the section ends on it.

[70] However, in some suḷādis, other features are noted in a few instances, for both first and other sections, where conformance to theoretical descriptions of sālagasūḍa is not seen. These are as follows:

The refrain is not indicated.

Melody repetition is not as per the theoretical descriptions

Occurrence of akāra syllables (“a” or “iya” syllables) is not as per the theoretical descriptions

[71] The structure of the first section of a suḷādi could also be compared to the structure of the kṛti in some instances. A kṛti is a musical form of present-day South Indian art music. It has three sections: pallavi, anupallavi,and one or more caraṇams. For example, in the first section of the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu,” the first two segments together could be compared to the pallavi, the segments III and IV together to the anupallavi and the segments V to VIII together could be compared to the caraṇam of the kṛti as indicated in Table 15:

Table 15. Structure of a suḷadi section compared with the structure of a kṛti.

Table 16. Structural features of a suḷadi section compared with the structural features of a kṛti.

[72] In Table 16, we see the following features of the segments that resemble the features of the kṛti sections.

[73] The above feature of the kṛti, where the second half of the caraṇam has a melody identical to that of the anupallavi,is seen in the compositions of Tyāgarāja (1767–1847) and other composers in the post-Tyāgarāja period. In some kṛtis, such as those of Muddusvāmi Dīkṣitar (1776–1835), the second half of the caraṇam does go to higher pitch positions than the first half, but the melody of the anupallavi is not repeated in the caraṇam.

[74] It must be noted, however, that the conformance of the features of the first section of the suḷādi to the features of the dhruva prabandha and the kṛti is not seen in all suḷādis.

Tālas of Suḷādis

[75] An examination of the tālasseen in suḷādis has been carried out by the present author in the TMSSML suḷādi notations publication (Rao 2022a, 233–250). The tāla features can be summarised as follows.

[76] In many of the TMSSML suḷādi notations, the cycles (āvartas) of tāla seem to be indicated by vertical lines. In some notations, vertical lines are also placed to indicate the sub-units (aṅgas) constituting each cycle of the tāla. In some other suḷādi notations, the vertical lines do not seem to indicate the cycles—in these, the structure of the tāla āvartas is indecipherable. The following observations have been made with respect to those TMSSML suḷādi notations where the vertical lines appear to indicate tāla āvartas and/or aṅgas.

[77] The tālas that are seen in the TMSSML suḷādi notations are those which have been described as “suḷādi tālas” in the Caturdaṇḍīprakāśikā (CDP). In the notations, the order of the sections does not strictly follow the order of tālas given in CDP. In most suḷādis, not all suḷādi tālas described in CDP are present. In some suḷādis, the same tāla is assigned to two sections. [78] The suḷādi tālas mentioned in CDP are, in order: jhōmpaṭa, dhruva, maṭhya, rūpaka, jhampā, tripuṭa, aṭha,and ēka. In CDP, these tālasare described in the chapter on svara (musical notes) (CDP 3.81–115). In the chapter, the structures of the tālas are given as part of the descriptions of alaṃkāras (patterns of svaras) set to the tālas. CDP states that the above tālas, along with ragaṇa maṭhya, should be used in gīta songs. While describing the alaṃkāra for ēka tāla (of two beats), he states that it may be substituted by ādi tāla, which is of four beats, as the former offers no aesthetic pleasure (CDP 3.108–110).

[78] The suḷādi tālas mentioned in CDP are, in order: jhōmpaṭa, dhruva, maṭhya, rūpaka, jhampā, tripuṭa, aṭha,and ēka. In CDP, these tālasare described in the chapter on svara (musical notes) (CDP 3.81–115). In the chapter, the structures of the tālas are given as part of the descriptions of alaṃkāras (patterns of svaras) set to the tālas. CDP states that the above tālas, along with ragaṇa maṭhya, should be used in gīta songs. While describing the alaṃkāra for ēka tāla (of two beats), he states that it may be substituted by ādi tāla, which is of four beats, as the former offers no aesthetic pleasure (CDP 3.108–110).

[79] As mentioned earlier, the suḷādi tālas, with the exception of jhōmpaṭa and ragaṇa maṭhya, exist in present-day South Indian art music. The total akṣara counts of the āvartas of the tālas are identical to those mentioned in the CDP. However, the order and span of the aṅgas (units) of the present-day suḷādi tālas are different from those described in the CDP.

[80] In the CDP, the structures of the suḷādi tālas have been described using the following aṅgas:

u anudruta, spanning 1 akṣara (time unit, beat)

o druta, spanning 2 akṣaras

o´ drutavirāma, spanning 3 akṣaras (druta augumented by 1 akṣara)

l laghu, spanning 4 or 5 akṣaras

l´ laghuśēkhara spanning 6 or 7 akṣaras

s guru, spanning 10 akṣaras

[81] The aṅgas drutavirāma and laghuśēkhara were actually the extensions of the aṅgas druta and laghu in the CDP. However, descriptions of laghu in other works written prior to and around the same time period as the CDP show that laghu by itself could have spans of 3, 4, 5, 7 or 9 akṣaras. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, such spans of laghu have been described in works such as Saṅgītasūryōdaya (SSU) and Rasakaumudi (RK). This has been discussed elsewhere.[20]

[82] In these works, the term jāti has been used to denote the span of the laghu. The jātis tryaśra, caturaśra, khaṇḍa, miśra, and saṅkīrṇa represent laghu spans of 3, 4, 5, 7 and 9 akṣaras respectively.[21] In the early 17th century, other works such as Rāgatālacintāmaṇi (RTC) and Tāladaśaprāṇadīpikā (TDDP) also note the presence of laghus of different spans of akṣaras(Krishnaveni 2008, 384). In the centuries that followed, the laghus of the akṣara spans of 3, 4, 5, 7 and 9 became the standard in South Indian art music. By the 20th century, the aṅgas drutavirāma, laghuśēkhara, and guru were no longer present in the suḷādi tālas of South Indian art music. Drutavirāma was replaced by laghu spanning 3 akṣaras. Laghuśēkhara of 6 akṣaras was replaced by a laghu of 4 akṣaras combined with a druta of 2 akṣaras; laghuśēkhara of 7 akṣaras was replaced by laghu of 7 akṣaras. In the CDP, ragaṇa maṭhya was the only tāla that had the aṅga guru in its structure. This tāla ceased to exist in South Indian art music by the twentieth century.

[83] Given below is a brief pictorial description of the structure of suḷādi tālas as described in the CDP and the corresponding equivalent tālasin present-day South Indian art music (Sambamoorthy, 1978, 86). In the section below, jhōmpaṭa tāla has been dealt with after ēka tāla: the reason for this will become obvious as the description of the tāla is discussed.

1) Dhruva

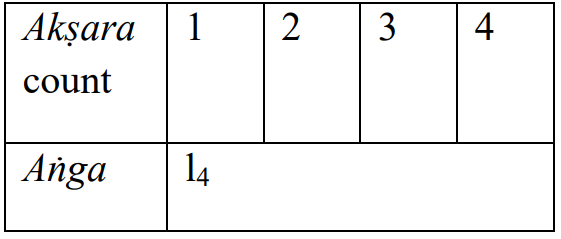

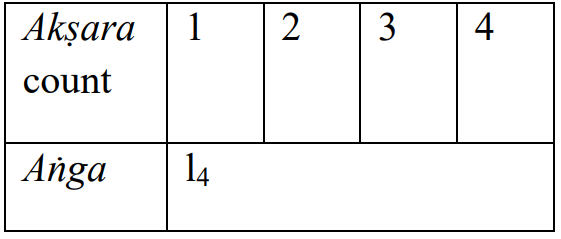

[84] The CDP structure of dhruva: There are two structures given for this tāla in CDP.

The first structure is laghu-guru denoted by l4 s10 . Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras and guru spans 10 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 17.

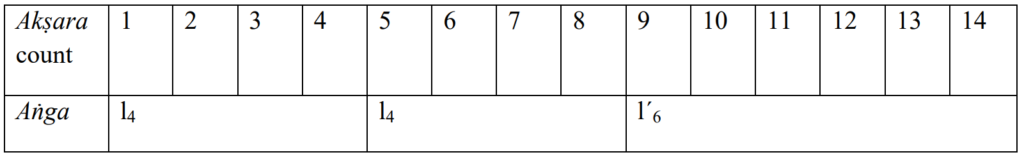

The second structure is laghu-laghu-laghuśēkhara denoted by l4 l4 l´6 : Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras and laghuśēkhara spans 6 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 18.

Table 17. The first structure of the tāla dhruva given in CDP.

Table 18. The second structure of the tāla dhruva given in CDP.

Table 19. The structure of the tāla caturaśra jāti dhruva in present day South Indian art music.

[85] In present-day South Indian art music, the tāla corresponding to the dhruva tāla of CDP is caturaśra jāti dhruva. The structure of this tāla is laghu-druta-laghu-laghu denoted by l4 o2 l4 l4. Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 19. In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in the cases where the aṅgas for dhruva tāla are decipherable, the above structure is seen. For example, in the suḷādi “Hejjege hejjege” set to the rāga dēvagāndhārī, the third section is set to dhruva tāla having a structure similar to this (Rao 2022a, 65).

2) Maṭhya

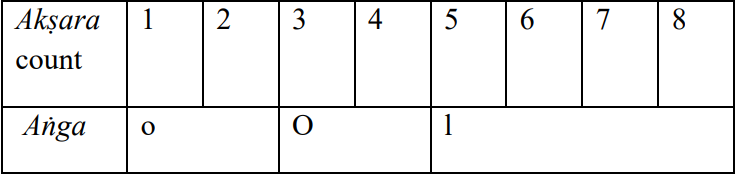

[86] The CDP structure of maṭhya is druta-laghu-laghu denoted by o2 l4 l4. Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 20.

Table 20. The structure of the tāla maṭhya given in CDP.

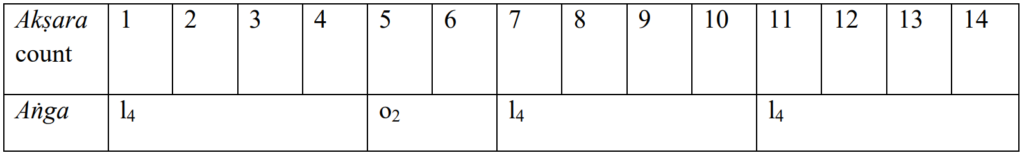

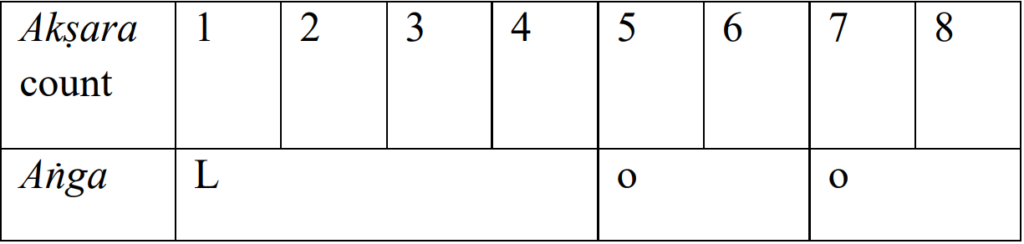

[87] In present-day South Indian art music, the tāla corresponding to the maṭhya tāla of CDP is caturaśra jāti maṭhya. The structure of the tāla is laghu-druta-laghu denoted by l4 o2 l4. Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 21.

Table 21. The structure of the tāla caturaśra jāti maṭhya in present day South Indian art music.

[88] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in several sections set to maṭhya tāla, the total span of the āvarta is 10 akṣaras. However, the splitting up of the āvarta into aṅgas is not decipherable. For example, in the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu” set to the rāga ārdradēśī, the third section set to maṭhya tāla displays a structure with the āvarta span of 10 akṣaras (Rao 2022a, 15).

[89] In this context, it is pertinent to examine the structure of the tāla ragaṇa maṭhya. CDP does not explicitly describe ragaṇa maṭhya, though it is mentioned as one of the tālasin which gītas should be sung (CDP, 3.111cd–112). It might be recalled that gīta in CDP refers to the type of song known as sālagasūḍa (CDP 8.4). In Sanskrit poetic meters, gaṇasare groups of syllables. Short syllables are called laghu and long ones guru. One of the gaṇas is ragaṇa which has the structure of guru-laghu-guru syllables. Transposing this definition of ragaṇa to the tāla system, we have the aṅgas guru-laghu-guru occurring in a sequence in ragaṇa. In the description of tālasin different musical treatises of the medieval period, we see that maṇṭha was the earlier form of maṭhya which had several structures, one of them being guru-laghu-guru.[22] Thus, ragaṇa maṭhya appears to be a variant of the tāla maṭhya having the structure guru-laghu-guru.

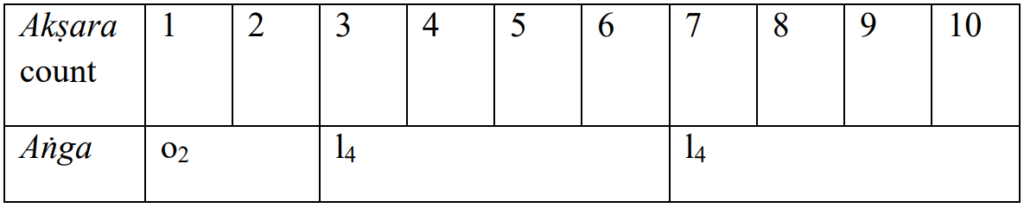

[90] In the description of maṭhya in present-day South Indian art music (given above, §87), we see that the middle aṅga—druta—has a span equivalent to half of the spans of the first and third aṅgas, which are both laghu of 4 akṣaras. Since ragaṇa maṭhya is apparently a variant of maṭhya, it is reasonable to assume that the ratio between spans of aṅgas in maṭhya is retained in ragaṇa maṭhya. Thus, in ragaṇa maṭhya, the span of guru would be twice that of laghu.

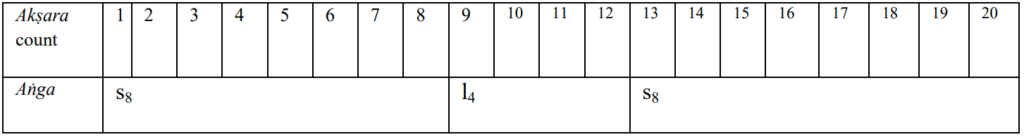

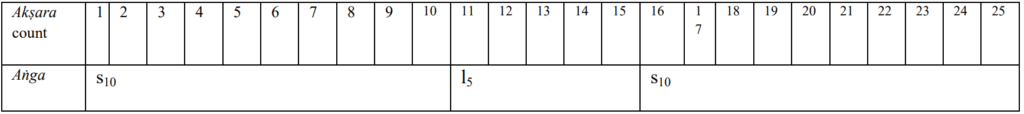

[91] The two structures that are possible for ragaṇa maṭhya have been illustrated in Tables 22 and 23 and can be denoted by s8 l4 s8 and s10 l5 s10.

Table 22. The first structure of the tāla ragaṇa maṭhya derived from the structure of the tāla maṭhya.

Table 23. The second structure of the tāla ragaṇa maṭhya derived from the structure of the tāla maṭhya.

[92] There is no equivalent to ragaṇa maṭhya in present-day South Indian art music.

[93] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in several sections set to ragaṇa maṭhya tāla, the total span of the āvarta is either 20 or 25 akṣaras. In some cases, the splitting up of the āvarta into aṅgas is determinable. For example, in the suḷādi “Kombu koḷalugaḷa”set to the rāga śrīrāga, the second section set to ragaṇa maṭhya tāla displays a structure close to the 20-beat structure of the tāla illustrated above (Table 22) (Rao 2022a, 181). In the suḷādi “Lakṣumiya mastakake” set to the rāga śuddha sāvērī,the second section set to ragaṇa maṭhya tāla displays a structure close to the 25-beat structure of the tāla illustrated above (Table 23) (Rao 2022a, 205).

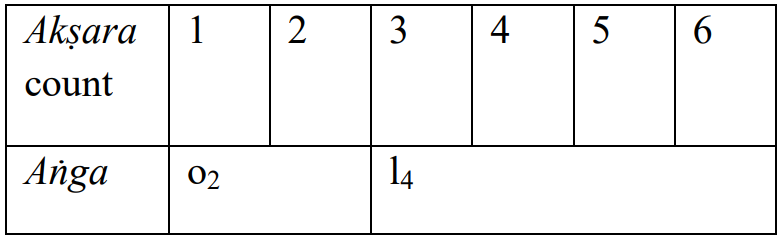

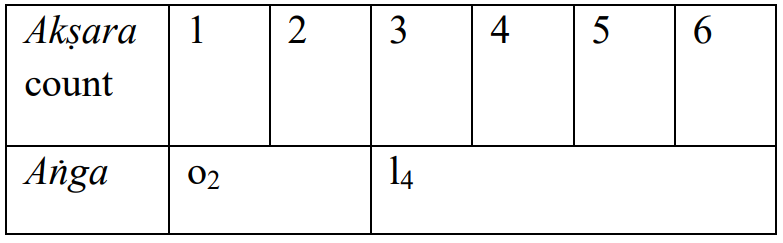

3) Rūpaka

[94] The CDP structure of rūpaka is druta-laghu denoted by o2 l4. Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 24.

[95] In present-day South Indian art music, the tāla corresponding to the rūpaka tāla of CDP is caturaśra jāti rūpaka. The structure of this tāla is druta-laghu denoted by o2 l4. Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 25.

[96] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in several sections set to rūpaka tāla, the total span of the āvarta is either 6 or 12 akṣaras. But in all the cases, the splitting up of the āvarta into aṅgas cannot be determined. For example, in the suḷādi “Hiṅgaḍala madhisudire” set to the rāga sālaṅganāṭa, the third section set to rūpaka tāla displays a structure having 6 akṣarasin the tāla āvarta, but no anga divisions are shown (Rao 2022a, 143).

Table 24. The structure of the tāla rūpaka given in CDP.

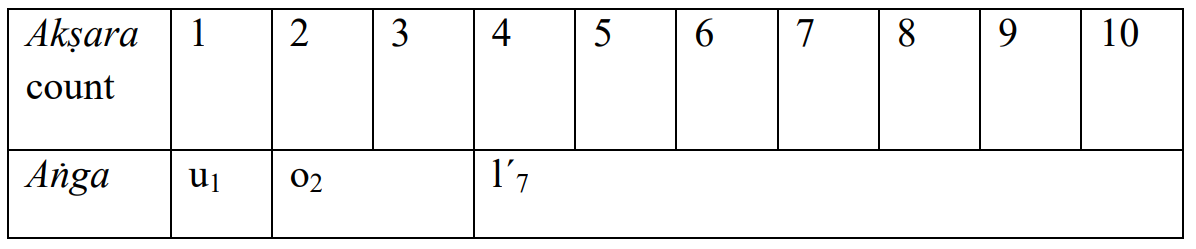

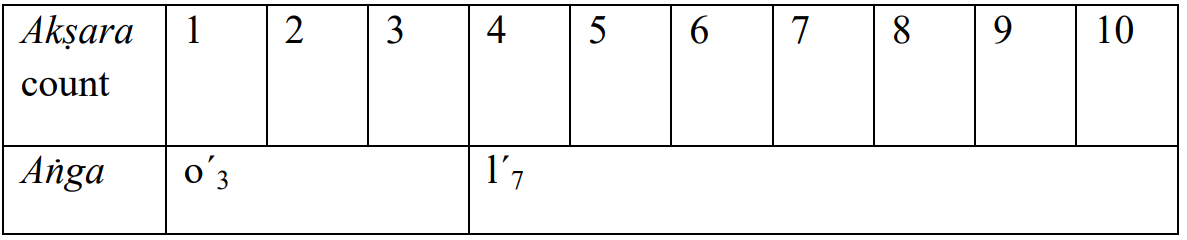

Table 25. The structure of the tāla caturaśra jāti rūpaka in present day South Indian art music.

4) Jhampā

[97] There are two structures in the CDP for this tāla.

The first structure is anudruta-druta-laghu denoted by u1 o2 l´7. Here, laghuśēkhara spans 7 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 26.

The second structure is drutavirāma-laghuśēkhara denoted by o´3 l´7. Here, laghuśēkhara spans 7 akṣaras and drutavirāma spans 3 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 27.

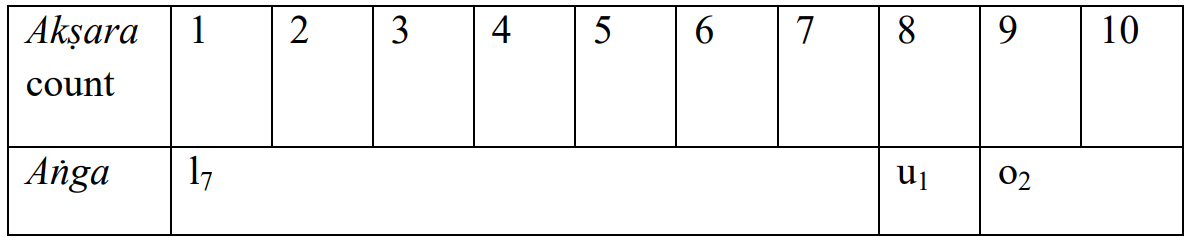

[98] In present-day South Indian art music, the tāla corresponding to the jhampātāla of CDP is miśra jāti jhampā. The structure of this tāla is laghu-anudruta-druta denoted by l7 u1 o2. Here, laghu spans 7 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 28.

Table 26. The first structure of the tāla jhampā given in CDP.

Table 27. The second structure of the tāla jhampā given in CDP.

Table 28. The structure of the tāla miśra jāti jhampā in present day South Indian art music.

[99] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in several sections set to jhampe/jhampya tāla, the total span of the āvarta is 10 akṣaras. But in all the cases, the splitting up of the āvarta into aṅgas cannot be determined. For example, in the suḷādi “Hiṅgaḍala madhisudire” set to the rāga sālaṅganāṭa, the fourth section set to jhampya tāla displays a structure having 10 akṣarasin the tāla āvarta, but no aṅga divisions are shown (Rao 2022a, 144).

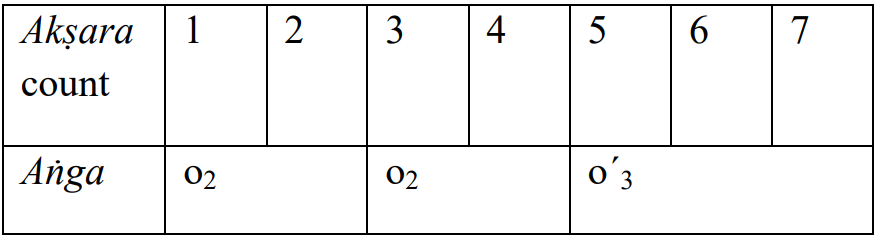

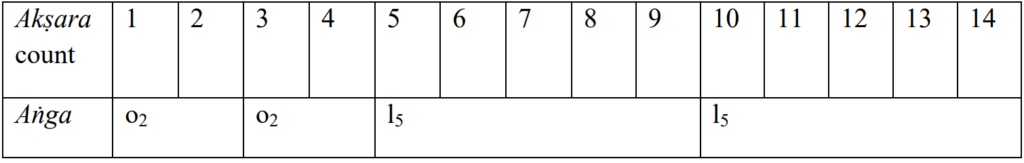

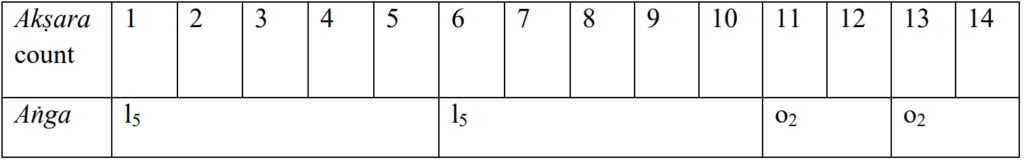

5) Tripuṭa

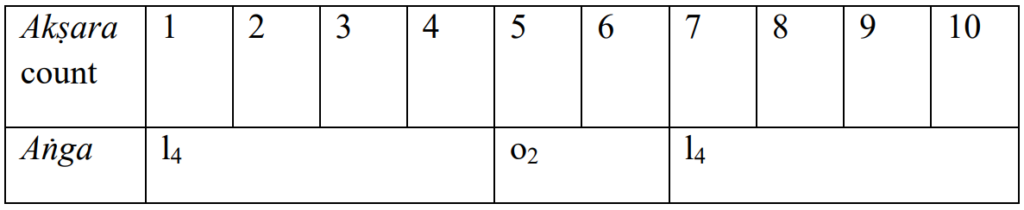

[100] The CDP structure for this tāla is druta-druta-drutavirāma denoted by o2 o2 o´3. This is illustrated in Table 29.

[101] In present-day South Indian art music, the tāla corresponding to the tripuṭa tāla of CDP is tiśra jāti tripuṭa. The structure of this tāla is laghu-druta-druta denoted by l3 o2 o2. Here, laghu spans 3 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 30.

[102] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in several sections set to tripuṭa tāla, the total span of the āvarta is 7 akṣaras. In some cases cases, the splitting up of the āvarta into aṅgas spanning 3+4 akṣarasis apparent. For example, in the suḷādi “Śrīnivāsana kāṇade”set to the rāga māruvadhanyāsī, the fifth section set to tripuṭa tāla displays a structure having 3+4 akṣaras in the tāla āvarta (Rao 2022a, 107).

Table 29. The structure of the tāla tripuṭa given in CDP.

Table 30. The structure of the tāla caturaśra jāti tripuṭa in present day South Indian art music.

6) Aṭa/aṭha

[103] The CDP structure for aṭha is druta-druta-laghu-laghu denoted by o2 o2 l5 l5. Here, laghu spans 5 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 31.

[104] In present-day South Indian art music, the tāla corresponding to the aṭha tāla of CDP is khaṇḍa jāti aṭa tāla, denoted by l5 l5 o2 o2. Here, laghu spans 5 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 32.

[105] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in several sections set to aṭa tāla, the total span of the āvarta is 14 akṣaras. In some cases cases, the splitting up of the āvarta into aṅgas spanning 5+5+2+2 akṣaras is apparent. But in others, the total span of 14 akṣaras can be sub-divided into two cycles of 7 akṣaras each, split up as 3+2+2. For example, in the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu”set to the rāga ārdradēśī, the last section (jati) displays a structure having 5+5+2+2 akṣaras in the tāla āvarta (Rao 2022a, 11). Interestingly, in the first section of this suḷādi, the tāla cycle of 14 akṣaras appears to be split into two units of 7 akṣaras, both having the structure of 3+2+2 akṣaras. This can be seen from the placement of vertical lines in the original unedited notation as well as the syllabic stresses of the lyrics of this section. There is also one instance of the tāla āvarta spanning 12 akṣaras. In the same suḷādi, the fourth section is set to aṭa tāla displaying a structure of 4+4+2+2. This implies that this structure has a laghu of 4 akṣaras (Rao 2022a, 16). The significance of this structure shall be discussed later in this section.

Table 31. The structure of the tāla aṭha given in CDP.

Table 32. The structure of the tāla khaṇḍa jāti aṭa in present day South Indian art music.

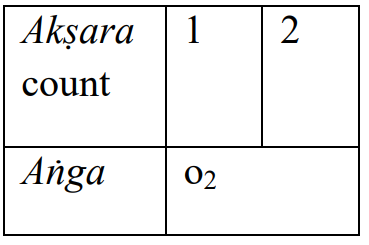

7) Ēka

[106] The CDP structure for ēka is druta denoted by o2. This is illustrated in Table 33. However, as mentioned earlier, the alaṅkāra for this tāla is substituted by the alaṅkāra for ādi tāla, having the structure of laghu denoted by l4. This is illustrated in Table 34.

[107] In present-day South Indian art music, the tāla corresponding to the ādi tāla of CDP is caturaśra jāti ēka tāla having the structure of laghu denoted byl4. Here, laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 35.

[108] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations, in several sections set to tāla ēka, the total span of the āvarta is 4 akṣaras. For example, in the suḷādi “Hejjege hejjege”set to the rāga dēvagāndhārī, the fifth section set to tāla ēka displays a structure having 4 akṣarasin the tāla āvarta (Rao 2022a, 67). But there is one instance of a suḷādi having a span of 8 akṣaras. In the suḷādi “Avana bhayadinda” set to the rāga śaṅkarābharaṇa, in the fifth section, this structure is seen (Rao 2022a, 160).

Table 33. The structure of the tāla ēka given in CDP.

Table 34. The structure of the tāla ēka given in CDP.

Table 35. The structure of the tāla caturaśra jāti ēka in present day South Indian art music.

8) Jhōmpaṭa

[109] The CDP structure of jhōmpaṭa is druta-druta-laghu, denoted by o o l. Here, the laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 36.

[110] This tāla does not exist in present-day South Indian art music. However, the structure is somewhat similar to the ādi tāla of present-day South Indian art music. The modern structure of ādi tāla is laghu-druta-druta, denoted by l o o. Here, the laghu spans 4 akṣaras. This is illustrated in Table 37.

Table 36. The structure of the tāla jhōmpata given in CDP.

Table 37. The structure of the tāla ādi in present day South Indian art music.

[111] We see from the above descriptions that the ādi tāla of CDP has a structure different from the ādi tāla of present-day South Indian art music. The former spans only 4 akṣaras but the latter spans 8 akṣaras. The present-day ādi tāla is closer to the structure of jhōmpaṭa tāla described in CDP.

[112] It is noteworthy that by the 20th century, a proliferation of the basic 7 tālas dhruva, maṭhya, rūpaka, jhampe, tripuṭa, aṭa, and ēka into a 35 tāla system is seen. Each of these 7 tālas admits 5 varieties of laghu, leading to a total of 35 tālas (Sambamoorthy, 1968: 46). For example, the five varieties of dhruva tāla are tiśra jāti dhruva (in which the laghu = 3 akṣaras), caturaśra jāti dhruva (laghu = 4 akṣaras), khaṇḍa jāti dhruva (laghu = 5 akṣaras), miśra jāti dhruva (laghu = 7 akṣaras) and saṅkīrṇa jāti dhruva (laghu = 9 akṣaras).

[113] The following observations can be made from the above discussion:

Dhruva tāla, tripuṭa tāla, aṭa tāla, and ēka tāla structures in TMSSML suḷādi notations, where the āvarta span and break-up into aṅgas is decipherable, seem close to the structures of the corresponding tālas in present-day South Indian art music.

In several sections set to maṭhya, jhampe, and rūpaka tālas in the TMSSML suḷādi notations, the āvarta counts are 10, 10 and 6 respectively, though the break-up of the āvartas into aṅgas is not decipherable in any of these structures.

The tāla jhōmpaṭa is not seen at all in any of the TMSSML suḷādi notations identified so far. However, there are many instances of ādi tāla being prescribed for some suḷādi sections in these notations. The ādi tāla is seen with 8-beat or 16-beat cycles in the notations as opposed to the 4-beat structure described in CDP. As described above, the total length of a cycle of tāla is identical for jhōmpaṭa and ādi tālas, though the order of the constituent aṅgas is not the same. Therefore, it is likely that ādi is used in place of jhōmpaṭa in the notations.

The tāla “ragaṇa maṭhya” is seen in some TMSSML suḷādi notations. In these notations, two varieties of ragaṇa maṭhya—with the lengths of 25 akṣaras and 20 akṣaras—are seen. The former has gurus of 10 akṣaras each and a laghu of 5 akṣaras, and the latter has two gurusof 8 akṣaras each and a laghu of 4 akṣaras (Rao 2022a, 237). There is also an instance of a suḷādi section set to aṭha/aṭa tāla with a structure of 4+4+2+2 having a laghu of 4 akṣaras as opposed to the laghu of 5 akṣaras mentioned in CDP. These suggest that the same tāla could have different akṣara spans (Rao 2022a, 247).

The akṣara counts of 12 for rūpaka tāla and 8 for ēka tāla are seen in a couple of instances. These suggest a possibility of “dvi-kale,” that is, two svaras being sung for an akṣara. This has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Rao 2022, 246).

[114] Some conventions are seen in the TMSSML suḷādi notations. The second section is always set to maṭhya or ragaṇa maṭhya. The final section is set either to ēka or aṭha. Dhruva and aṭha are prescribed for more than one section in some cases, but repetition of other tālas is not seen. The order of rūpaka-jhampa-tripuṭa is followed in most cases.

[115] In the TMSSML suḷādi notations in one suḷādi section, a special instance of rūpaka is seen. This is dhruva-rūpaka, where the first segment of the section spans 10 akṣaras. The subsequent segments span 6-akṣara āvartas and there are 2 akṣaras at the end of the section so that the total akṣara count is a multiple of 6. A detailed discussion on this has been carried out elsewhere (Rao 2022, 245).

[116] Tālas prescribed for some suḷādis were also compared between the TMSSML notations and suḷādi publications. Differences were found in the tālas mentioned in the two sources. For example, in the suḷādi “Acyutānta gōvinda,” the TMSSML notation gives the tāla for the first section as jhampa whereas the suḷādi publication mentions the tāla dhruva for the first section (Gorabala, 1958b, 44).

Melodic Features of the Suḷādis

[117] Some observations about the melodic features of suḷādis made by the present author in the TMSSML suḷādi notations publication are summarised here.[23] TMSSML notations of suḷādis typically give the rāga name at the beginning of the notation, sometimes followed by the name of the parent scale (mēla).[24] The constituent svaras of the rāga are not indicated, so the exact svaras are difficult to determine. Another problem is the absence of symbols to indicate registers in the notations. Finer nuances in the melodies, such as embellishments (gamakas) and the speed of rendering of the notes (kāla pramāṇa) are also not indicated in the notations. The comparison of rāga features of the suḷādi to theoretical descriptions in musical treatises has been done with some assumptions. A complete picture of the rāgas in the time period of the composition of the suḷādis can only emerge from a thorough study of a larger number of songs, both suḷādis and others, stated to be in those rāgas.

[118] Some of the rāga names noticed in the suḷādi notations are those which are known even in present-day South Indian art music, such as bhairavi, sāvērī, gauḷa, rītigauḷa, and śaṅkarābharaṇa. There are other rāga names not performed much as part of South Indian art music in the present day, such as ārdradēśī, sālaṅganāṭa, guṇḍakriyā, and gumma kāmbōdhī. In the former case, some of the melodic passages of the suḷādi notations display certain features of the rāga which are not found in the present-day form of the rāga. Though the names of the rāgas are the same, the grammars of the rāgas—including the pitches used, the initial/predominant/final notes and prominent note-phrases—appear to have undergone several changes.

[119] An interesting feature of the notations is the use of rāgas that are not of the “superior” (uttama) class as designated by the musicologists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—Rāmāmātya and Sōmanātha. It is possible that the Haridāsa composers took up rāgas that seemingly did not have high melodic potential, and expanded the scope of these rāgas by composing new melodies. It is noteworthy that many of the suḷādi svara passages are cited in RL-S and SSA, and the rāga features seen in the suḷādi notations are close to those described in these texts.

[120] The rāga ārdradēśī, to which the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu” (illustrated in the section 4.2) has been set, has been mentioned in the musical treatise Svaramēlakalānidhi (SMK) of the sixteenth century, and also in CDP of the early seventeenth century. The SMK classifies it under the śuddharāmakriyā mēla and the CDP under the gaula mēla (Ramanathanan 2021, 2–62). But a melodic picture of the rāga that is close to the present suḷādi emerges only in the texts RL-S and SSA belonging to the late seventeenth/early eighteenth century. These two works describe the saṃpūrṇa characteristic of the rāga (having all seven notes) and mention that it belongs to the mālavagaula mēla.

[121] In RL-S, there are svara passages from an ālāpa, a ṭhāya, a gīta, and a suḷādi along with the description of the rāga ārdradēśī. The description of the rāga and the citation of a passage from the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu” (segment II of section II of the suḷādi), as given by Hema Ramanathan (2021, 2–59) are reproduced here. These have been trans-notated and translated by her from the original Telugu text into English:

[122] The following is the description of the rāga:

“Ārdradēśi (suitable for ghana alone) takes the mēḷa of māḷavagauḷa. It is a sampūrṇa rāga. Examples of the svara movement in ascent and descent.”[25]

[123] The following is the citation of a passage from the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu”:

[124] For the same rāga, SSA gives the same examples and a similar description. The description of the rāga and the suḷādi citation, as given by Ramanathan (2021, 2–60), are reproduced here—again, these have been trans-notated and translated from the original Sanskrit text into English.

The following is the description of the rāga:

“Ārdradēśī originates in the mālavagaula mēla. It is sampūrṇa, with sa as graha and nyāsa. It is said to be sung at daybreak.”

[125] The following is the citation of a passage from the suḷādi “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu”:

This is [rāga] ārdradēśī.”

[126] The svara phrases given as examples in these two works have the svara ni (the note B in the suḷādi staff-notation transcriptions (Examples 1–3)) occurring in some instances, and omitted in other instances. Repetitions of the svara ga (E ) and dha (D♭) are seen in some phrases. Rāgalakṣaṇamu of Mudduveṅkaṭamakhin (RL-MV) and SSP, the text that follows RL-MV, Saṅgrahacūḍāmaṇi (SCud), Saṅgītasārasaṅgrahamu (SSS), Mahābharatacūḍāmaṇi (MBC), and Rāgalakṣaṇa (RL) of the eighteenth/nineteenth centuries also classify the rāga under the mālavagaula mēla (with D♭ and A♭). RL-MV and SSP give phrases with ni in descent, whereas SCud, SSS, MBC, and RL omit ni in descent.

[127] The suḷādi notation of “Dēha jīrṇavāyitu” does not offer any indication of the varieties of the svara used or the mēla to which the rāga belongs. However, when we examine the musical phrases of the suḷādi, we find that the phrases are close to the version of the rāga as seen in RL-S, SSA, RL-MV, and SSP rather than the other texts mentioned. It is also seen that Segment II of Section 2 of the suḷādi is cited as an example for ārdradēśī in RL-S and SSA. It therefore appears that the features of the rāga found in the suḷādi are close to what has been described in RL-S and SSA, and we can therefore plausibly attribute this song to the mālavagaula mēla.

Summary